Date: 2025-11-19 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00027618

US POLITICS

SENATOR BERNIE SANDERS

WP: After two failed presidential bids, the Vermont

senator is learning to wield his influence in new ways.

SENATOR BERNIE SANDERS

WP: After two failed presidential bids, the Vermont

senator is learning to wield his influence in new ways.

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vermont) twice sought the White House. He ended up

as chairman of a Senate committee. Sanders says he's trying to accomplish

his same goals, using different tools. (Matt McClain / The Washington Post)

Original article: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2024/10/25/bernie-sanders-2024-election-campaigning-efforts/

Peter Burgess COMMENTARY

Senator Bernie Sanders is now one of the older members of the Senate ... but for me, still a breath of fresh air.

I am on the record saying that President Biden has been one of the most successful Presidents in terms of meaningful legislation passed, and in no small part this has been because of the collaboration there has been by the progressive community of Democrats that includes Sanders and the more conservative democrats of which Biden is part! Vice President Harris also had a role in enableing impressive legislation by casting tie-breaking votes in critical situations several times!

The Biden era legislation has been perhaps as big as the legislation of Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson combined! This contrasts with the almost non-existent meaningful legislation of the Trump presidency!

Peter Burgess

After two failed presidential bids, the Vermont senator is learning to wield his influence in new ways.

Written by Dan Diamond ... Dan Diamond is a national health reporter for The Washington Post. He joined The Post in 2021 after five years at Politico, where he won a George Polk award for investigating the Trump administration's response to the coronavirus pandemic.follow on X @ddiamond

October 25, 2024 at 6:00 a.m. EDT

Bernie Sanders is running. No — not like that.

The Vermont senator is striding up the stairs — two at a time — as he hustles between congressional hearings. Sanders testified on the second floor in the Dirksen Senate Office Building to support a Vermont judge’s nomination. Now, he needs to get back to another hearing he’s chairing on public education on the fifth floor. And in 90 minutes, he must be at the airport to fly to Ohio to meet with union officials, hold a rally and convince his antiestablishment supporters that voting for a Democratic president is their best bet for real change.

It’s an ambitious agenda that faces real obstacles: A divided electorate. Well-heeled opponents. A Senate elevator a few minutes ago that refused to move.

“Not a good elevator,” Sanders barks, stomping out in search of a better one.

Sanders is running — around Capitol Hill and around the country — to fight corporate interests, to champion liberal causes and, especially, to stop Donald Trump. The 83-year-old progressive leader is trying to use the power he has accumulated over a lifetime in politics, particularly in the past decade after emerging — like the fully formed, Brooklyn-born grandpa that he is — onto the national scene and winning millions of fans.

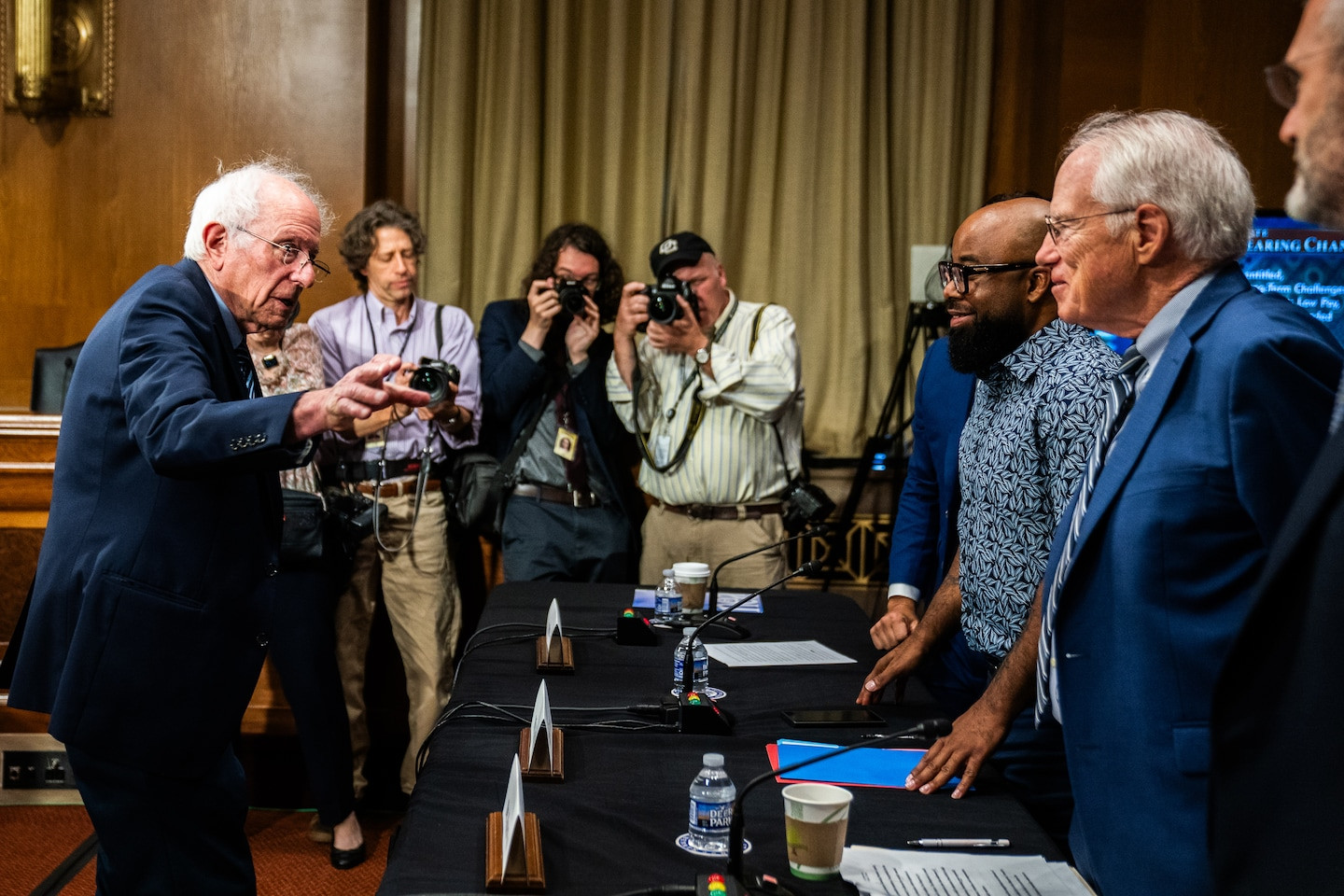

Sanders leads a Senate hearing in June on the challenges facing public schools. As chairman of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, Sanders has shaped the panel to focus on his priorities, such as boosting social services and fighting corporate power. (Demetrius Freeman/The Washington Post)

What Sanders is most certainly not doing on this June morning: running for president again, despite entreaties from supporters whose pleas grew fervent as Democrats’ hopes teetered this summer.

Now Joe Biden, whose long relationship with Sanders deepened as the two men competed for the White House in 2020, is out of the race. Kamala Harris, who drafted off Sanders’s progressive bona fides in her last presidential campaign before rejecting his signature Medicare-for-all plan, is in.

And Sanders is still ever-present, going on national TV shows, sitting for podcasts and rallying in battleground states. He’s using his platform as chairman of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee — an often-genteel congressional panel that has undergone a Sanders-style attitude adjustment since he took over last year — to bully industry executives and win victories that Democrats can tout at the ballot box.

And on this morning, even as he juggles two hearings and an impending flight, he’ll stop to give an interview to a crush of journalists, with a Fox News reporter pressing him on protégé Rep. Jamaal Bowman’s upcoming primary in New York. (Bowman will lose to a candidate backed by the Democratic Party establishment.) He’ll be confronted by a leafleteer about the Israel-Gaza conflict. He’ll be mobbed by fans who want selfies at the public-education hearing as he tries to make his way back to his office.

The Washington Post followed Sanders over the past 20 months, interviewing him as he took over the Senate health panel, pushed new policies and campaigned for liberal issues across the country. The Post also spoke with more than two dozen current and former Sanders staffers, allies and colleagues about his agenda, many of whom spoke on the condition of anonymity to describe private discussions.

What emerged: a more pragmatic Sanders than the iconoclast who identifies as an independent but upended the Democratic Party with his two presidential runs, particularly with his outsider campaign in 2016.

Sanders greets witnesses before his panel's June hearing on the challenges facing public schools. (Demetrius Freeman/The Washington Post)

Not everyone agrees that this is a good development.

“He dropped the single-payer,” said Ralph Nader, the liberal activist who also ran for president and once considered Sanders a close ally. The two progressive icons have had a falling-out, Nader said, which he blamed on Sanders focusing on other priorities rather than continuing to crusade for Medicare-for-all, his plan to overhaul the U.S. health system and shift Americans to government health insurance. “Bernie, you got millions of people who voted for you, in part because you wanted single-payer,” Nader lamented.

But for Sanders the fight remains the same: Take on corporate power. Lower drug prices. Expand access to health coverage — through Medicare-for-all, if possible.

And stop a man he calls a dangerous bully and pathological liar.

“This country cannot sustain four more years of Donald Trump,” Sanders said in a recent interview. “I’m going to do everything I can to see that he is defeated.”

The octogenarian senator is also running for reelection himself, seeking six more years in office — but at a moment when age has often defined the political debate, no one is saying Bernie Sanders is too old.

“I don’t understand where he gets the energy,” a former aide said. “I think it’s because he’s always angry.”

Sanders unveils the latest version of his Medicare-for-all legislation on Capitol Hill in May 2023. The senator, joined by allies such as Reps. Pramila Jayapal (D-Washington) and Jim McGovern (D-Massachusetts), has spent much of his career pushing for universal health care. (Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post)

May 2023: Rallying for health care

Bernie Sanders is feeling the love.

The auditorium in the basement of the U.S. Capitol is packed — dotted with doctors in white coats and nurses in red National Nurses United T-shirts — as Sanders enters to a 20-second standing ovation. “I love you, Bernie,” one woman shouts. “Love you, too,” he shoots back.

The room is crackling with nerves and excitement. Sanders, who has been chairman of the Senate’s health committee for three months, is set to reintroduce his signature Medicare-for-all legislation the next day. He’s introduced similar legislation in three previous sessions of Congress. It’s never made it to the Senate floor.

“This is a struggle that we are going to win. If not today, we will win it tomorrow,” Sanders vows to the health workers and his political allies assembled this evening.

Medicare-for-all had been core to Sanders’s breakthrough in the 2016 presidential campaign, as the lawmaker’s decades-old message — that every American should be covered through a single government health plan — suddenly became a national rallying cry. Other lawmakers took note, particularly after Trump’s own populist message helped him win the White House that year.

So when Sanders announced his Medicare-for-all legislation in September 2017, Harris, then a senator from California, became the first to sign on. A slew of other Democrats positioning for presidential runs — Sens. Cory Booker (D-New Jersey), Kirsten Gillibrand (D-New York) and Elizabeth Warren (D-Massachusetts), among others — quickly followed.

But as the Democrats’ presidential nominating contest got underway in 2019, lawmakers started hearing from voters worried about losing their private health insurance. Polls showed that even the party’s base voters, while supportive of Medicare-for-all, preferred other health-care strategies.

Harris backed off, introducing a compromise in 2019 that would have preserved a role for private health insurers. The move infuriated Sanders campaign officials, who believed she was seeking to cloak herself in Sanders’s branding even as she offered a watered-down version of his ideas.

Then Biden — one of the few candidates who had rejected Medicare-for-all — won the Democratic nomination and the presidency, effectively ending the debate.

Four years later, Democratic leaders have coalesced around the idea that Medicare-for-all is too politically risky. Harris has now repudiated her past support, saying she would incrementally build on the Affordable Care Act rather than seek a dramatic overhaul of the U.S. health system. (That hasn’t stopped Trump from attacking Harris over her past embrace of Sanders’s plan.)

And while Sanders was named chairman of the Senate Budget Committee in 2021 and held a hearing on Medicare-for-all the following year, he has yet to hold another hearing since taking over the more sweeping health committee in February 2023.

Nader contends that Sanders “made peace” with Democrats by deprioritizing Medicare-for-all in exchange for more party influence.

But Sanders scoffs at the suggestion that he’s backed off his signature legislation. “I have not, in one tiny scintilla, retreated from Medicare-for-all,” the senator says.

The issue is a simple vote-counting problem, he added. There are just 14 Senate Democrats co-sponsoring his bill in this Congress — and zero Republicans.

“It ain’t gonna happen,” Sanders says, sitting at a table in the health committee’s hearing room. “Right now, what I, as chairman of this committee, am working on are things that can get done and have an impact on the American people.”

President Joe Biden and Sanders, who have forged a close working relationship, walk toward the Oval Office of the White House in April, joined by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-New York) and Sen. Edward J. Markey (D-Massachusetts), who are frequent allies of Sanders and his liberal agenda. (Demetrius Freeman/The Washington Post)

April 2024: Penetrating the White House

Bernie Sanders watches stoically from the front row as one of his latest priorities — lowering the cost of inhalers — flashes on the screens flanking the stage in the Indian Treaty Room. Ten feet away, Biden mumbles and stumbles through a speech peppered with Sanders-isms — lambasting the greed of Big Pharma and drug companies that use patents to hike up their prices.

The centrist president and the liberal senator think differently, talk differently and have different core supporters. But in Biden, Sanders sees an opportunity for his ideas to become law — channeled through a White House that is finally listening to him.

The two men dueled for Democrats’ presidential nomination in 2020, with Sanders ultimately denied the prize for the second time in four years. But unlike the bad feelings that emerged between Sanders and Hillary Clinton in 2016 and lingered after she edged him out for the nomination, Biden and Sanders stayed friendly and respectful — a dynamic formed when they briefly overlapped in Congress and cemented when Biden, as vice president, praised Sanders instead of dissuading him from challenging Clinton.

That relationship paid off five years later, when Sanders dropped out of the presidential race and swiftly endorsed Biden. The two men hammered out a “unity platform” that called for cracking down on the drug industry and other Sanders priorities; strategized after the election about the transition; and took other steps that endeared Sanders to the incoming president.

“We were in the Senate together. We campaigned for president together. One of us won, one of us lost — but nonetheless,” Sanders said in a recent interview, reflecting on their past rivalry and current dynamic, “our wives are pretty good friends.”

That common ground didn’t guarantee Sanders’s satisfaction with the new president. Early in his tenure as Senate health committee chairman, he announced that he was so frustrated by Biden’s lack of strategy to lower drug costs that he threatened to block his nominees.

“I wanted to make clear to the president … I will oppose any nominee who is not prepared to stand up to the pharmaceutical industry,” he told The Post in May 2023, sharing a letter that he had just sent Biden saying as much.

As health committee chairman, Sanders controlled the calendar for when many Biden health, education and labor nominees would get their required Senate hearings; for nearly five months, he refused to schedule a hearing for Biden’s nominee to lead the National Institutes of Health.

Shuttle diplomacy and pledges from the Biden administration ended the standoff; the new NIH director was confirmed in November 2023.

Meanwhile, Sanders and his allies in Congress launched an investigation into the high prices of inhalers sold in the United States, securing promises from drug companies to lower their costs.

Now it’s April, and Biden is celebrating those lower inhaler costs, name-checking Sanders 18 times in his White House speech.

This event — and what it represents — is one reason Sanders is talking comparably less about Medicare-for-all and much more about fighting Big Pharma. The Inflation Reduction Act, which Biden signed into law in August 2022, contains an array of new initiatives to lower drug prices, pulled straight out of the Sanders playbook. Medicare can finally negotiate directly with drug companies on prices. The cost of insulin is now capped at $35 per month for seniors.

White House leaders see an opportunity of their own in Sanders: to piggyback on his progressive agenda and tout his accomplishments as the president’s, too.

“I’m proud that my administration is taking on Big Pharma in the most significant ways ever,” Biden says that day. “And I wouldn’t have done it without Bernie. And Bernie got a — you know, look, Bernie was the one who was leading the way for decades in which we’re — why we’re here today.”

Rep. Jamaal Bowman (D-New York) introduces Sanders at a campaign rally at St. Mary’s Park in the Bronx in June. Bowman, a Sanders protégé, later lost his primary to a candidate backed by the Democratic establishment. (Yana Paskova for The Washington Post)

June 2024: Hitting the campaign trail

Bernie Sanders will never be president, barring a political surprise greater than this summer’s candidate switcheroo.

So instead of being flanked by a small army of aides and security, the senator walks through Reagan National Airport in June without a single staffer accompanying him. Rather than take a private government jet, where all his needs would be met, Sanders is the one lifting his travel-worn green suitcase and wedging it into the overhead bin on a small airplane heading to Cleveland.

Sanders is flying to Ohio because he’s rallying supporters on a ballot initiative that would raise the state’s minimum wage to $15 per hour, from $10.45. The union-backed effort lines up with Sanders’s own policies. (If anything, it comes up a bit short; Sanders wants a $17 per hour national minimum wage.) But Sanders is also descending on the state because of national politics: He and his team believe that a ballot measure to hike the minimum wage will motivate Ohioans who are otherwise lukewarm on voting for Democrats. It’s a similar strategy to how abortion ballot measures have drawn voters to the polls.

The senator remains a widely recognized national figure, whose appeal cuts across age and ethnicity, partly because of his political style, and at least a little bit because he’s so meme-able. He’s also more popular than Biden, Trump and Harris — and virtually every other politician Ipsos pollsters asked about in a survey released in April.

It’s a reality illustrated by the parade of people who approach Sanders as he waits for his flight at Reagan — service workers who urge him to run for president again, health-care researchers who say they admire him, even a self-described Republican union machinist who says that he doesn’t like Democrats but would vote for Sanders.

But the most revealing interaction might have been with a woman who approached Sanders to tell him he’s her “hero.” Minutes later, the woman and her husband, wearing N95 masks, confessed to The Post they had cast their votes for Biden in the 2020 Virginia primary. Both are retired lawyers who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they didn’t want to publicize their voting history.

“As much as we like Bernie Sanders, we don’t regret that decision,” her husband says. “We still think that Biden was the guy who could beat Trump — and he did.”

His wife agrees: “I wish we could elect someone as progressive as Bernie Sanders. I just don’t think that’s going to happen, at least not anytime soon.”

On the plane, a young man asks for a photo with Sanders while walking past his seat, but the senator waves him off. Sanders has matters to discuss with his chief of staff, Misty Rebik, who had been waiting at the gate and is now sitting next to him. The two spend several minutes wrestling over the continued fallout of the Gaza conflict. While Sanders has castigated Israel’s decisions, he has stopped short of using the word “genocide” to describe the country’s attacks in Gaza, a decision that has frustrated some political allies who want the Jewish senator to use the term.

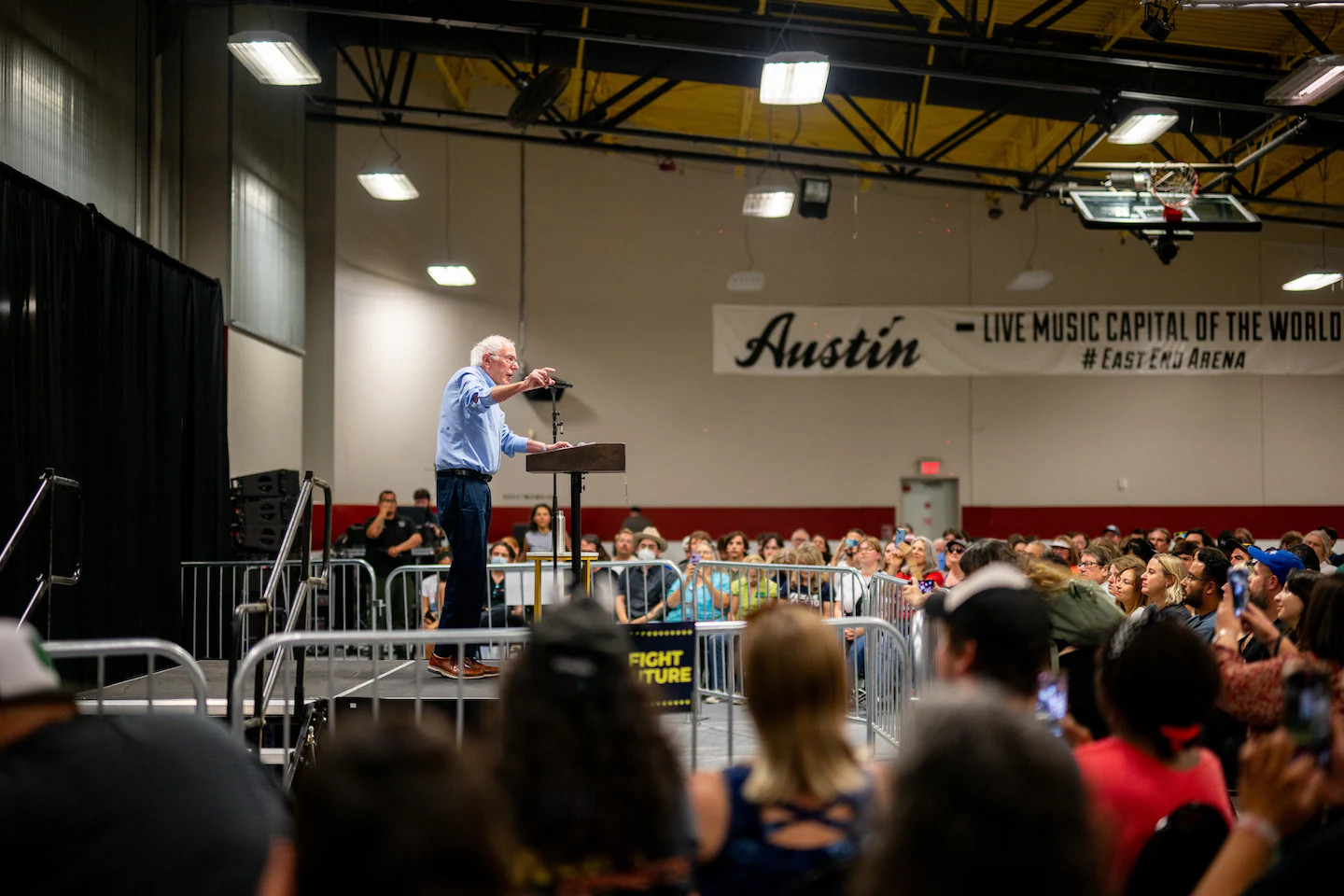

Sanders speaks during a “Our Fight, Our Future” rally in Austin this month. Sanders said he visited Texas ahead of the voter registration deadline in an effort to turn out young voters. (Brandon Bell/Getty Images) Sanders unveils the latest version of his Medicare-for-all legislation on Capitol Hill in May 2023. The senator, joined by allies such as Reps. Pramila Jayapal (D-Washington) and Jim McGovern (D-Massachusetts), has spent much of his career pushing for universal health care. (Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post)

“I wish they’d follow your lead,” Rebik tells him.

Nothing has shaken Sanders’s faithful supporters more than what has unfolded in the Middle East, an issue that has divided Democrats and turned some liberals against a White House they say is doing too little to stop the conflict. Sanders will end up spending much of 2024 battling with the White House over its Gaza policies, with the senator trying to block U.S. arms sales to Israel.

And as Sanders hits the campaign trail, his team has been debating ideas to amp up opposition to the war, particularly when Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister, is set to address Congress in late July. Under consideration: counterprogramming with the likes of Cindy McCain, executive director of the World Food Program, who had warned that Gaza was descending into famine. (Sanders’s office ultimately dismissed the idea.)

Once Sanders is on the ground in Ohio, almost no minute is spared. He films a social media video on the state’s minimum-wage ballot initiative in the 100-degree-heat — and after he huddles with his staffers to watch the draft, unsatisfied with the quality of his riff, they shoot it again. He sits for interviews with local journalists. He leads a roundtable discussion with two dozen activists and union members, including leaders from One Fair Wage, an organization working to raise the minimum wage.

Then he takes the stage in a union hall, delivering a version of his populist message that he made famous when running for president.

“Working people are sick and tired of being ripped off,” Sanders thunders to the crowd, urging them to support the minimum-wage ballot initiative. “People on top have endless amounts of money. They can do anything they want … [and they’re] fighting us on this thing.”

Sanders isn’t the only national politician in Cleveland tonight. Trump is just a short drive away at a fundraiser, charging up to $250,000 per couple. The contrast isn’t lost on Sanders, or his supporters in the union hall, some of whom hold signs or approach him with pleas to run for president yet again.

A week later, national Democrats will reach their own conclusion: Biden shouldn’t run again, after the 81-year-old incumbent badly struggles in his prime-time debate with Trump.

But as their colleagues in Congress start to turn on Biden, Sanders and his ally Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-New York) sense an opening. The progressive senator and the congresswoman, who’s grown from a volunteer on his 2016 campaign to a partner in Congress, publicly champion Biden and privately urge him to embrace more liberal ideas. Their pitch: It’s his best path to fire up Americans feeling lackluster about his presidential campaign. And Biden will listen, announcing new proposals such as ending medical debt in a speech that would win plaudits for his energy and ambition.

The short-lived surge is drowned out by growing calls for Biden to drop out.

“I wanted him to stay in the race,” Sanders acknowledged in an interview a few days after Biden ended his campaign. “Despite the very bad debate performance — no great secret — I thought he had an excellent chance to win the election. I thought he would win it because his appeal to working-class voters and the very strong agenda that he was bringing forth.”

Sanders delivers opening remarks during a Senate hearing with Lars Fruergaard Jorgensen, the president and CEO of Novo Nordisk, in September. Sanders has been locked in a public battle with the pharmaceutical company over the prices of its drugs to treat diabetes and obesity. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

September 2024: Steering a panel

Bernie Sanders sought the White House. He ended up with a Senate committee.

It’s the closest we’ll likely get to seeing how a Sanders presidency would have unfolded — a series of threats and showdowns, as the Vermont senator has tried to force change rather than wait for Congress to act.

Sanders has pursued drug-price cuts in part by targeting specific drugs and products, and threatening to subpoena executives when they don’t cooperate. He’s conducted investigations into major companies such as Amazon and Starbucks, releasing reports that argue they’ve failed their workers.

Sanders even took his fight to the nation of Denmark — whose socialist health-care system he admires, but whose economy is buoyed by billions of dollars in sales of weight-loss drugs Ozempic and Wegovy. Earlier this year, Sanders ran a front-page editorial in one of the country’s leading newspapers, pleading in Danish for citizens to pressure the Danish pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk to rein in prices because the drugs are driving up health costs in the United States and other countries. He threatened to subpoena the company’s top U.S. executive until the Danish CEO agreed to testify.

Today, I wrote an op-ed on the front page of Danish paper Politiken to appeal to Denmark’s longstanding commitment to social justice and to win their help in urging Novo Nordisk, the most profitable company in Denmark, to reduce the outrageous price of Ozempic & Wegovy in the US.

“You use the tools that you have,” Sanders said in an interview. “If you’re running for president, you speak to millions of people. ... As a committee chairman, you have different tools, and use those tools for the same purpose.”

His Republican counterparts have taken a dimmer view of Sanders’s tactics, arguing that his hearings and investigations are often political theater, with little lasting effect. Sen. Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, the panel’s top Republican, has repeatedly complained that Sanders has prioritized a handful of his favorite health-care and labor issues rather than focus on the committee’s more routine work, like advancing legislation or conducting bipartisan oversight.

“We are a year and a half into this Congress, and we have not had a single hearing on the state of primary or secondary education,” Cassidy said at a May 2024 hearing on dental care, lamenting the panel’s failure to focus on issues like a national debacle with student financial aid forms. “We are the health, education, labor and pension committee,” he emphasized.

Sanders concedes that being a committee chairman — and all the accompanying responsibilities — isn’t always a natural fit. A lawmaker who built a reputation as a fierce independent now must lead reviews of his colleagues’ legislation and sit through other congressional tasks that his allies say can bore him.

“If I were operating just by myself, and listed the top 20 things that I wanted to go after, it would not necessarily be all of the hearings and markups that we have,” Sanders said in an interview.

His allies say he’s learning on the job — and that his influence is seeping into the committee. They point to Steward Health Care, a chain of for-profit hospitals that went bankrupt, as Exhibit A.

The panel had been investigating Steward, asking why executives including then-CEO Ralph de la Torre were drawing multimillion-dollar compensation as the system struggled to buy supplies and pay bills. In a September hearing, nurses warned that Steward’s cost cuts had threatened their ability to deliver safe and timely care to patients.

But de la Torre defied the panel’s subpoena to appear and answer questions.

Now, Sanders and Cassidy are working together in a bid to send de la Torre to prison. Their panel, followed by the full Senate, voted last month to ask the Justice Department to pursue criminal contempt charges against him, the first time the Senate chamber has targeted an individual in such a manner in more than 50 years, according to the Senate historian.

For Sanders, the Steward episode embodies his philosophy: Greed shapes American health care, and it rests with lawmakers to combat it.

“Even though Dr. de la Torre may be worth hundreds of millions of dollars … if you defy a congressional subpoena, you will be held accountable, no matter who you are or how well-connected you may be,” Sanders said on the Senate floor in September.

Meanwhile, de la Torre has sued Sanders’s panel, claiming the committee was violating his rights by trying to force him to testify.

Sanders waits with other presidential candidates, including billionaire activist Tom Steyer, Sen. Cory Booker (D-New Jersey), then-Sen. Kamala Harris (D-California) and Biden before an October 2019 debate in Westerville, Ohio. (Aaron Josefczyk/Reuters)

What’s next

Bernie Sanders is — for the third time in eight years — stumping for a former rival to win the White House.

Sanders knows Kamala Harris a bit, first from her time in the Senate and then their shared experience on the presidential campaign trail before she dropped out in December 2019. She called him after Biden ended his campaign in July, seeking to shore up his support. She’s tough, he thinks, and can articulate Democrats’ positions better than an often-mush-mouthed Biden.

She can win, and keep Sanders’s agenda in play at the White House.

But she’s not Biden. They don’t have the years of shared life experiences that the two octogenarian men possess.

She doesn’t need Sanders’s energy the way Biden did; more than two decades younger than the sitting president, Harris has revitalized her party simply by replacing Biden as the nominee.

So will she listen to Sanders, the way Biden has for four years?

By October, Sanders is starting to get answers. A new Harris proposal would expand Medicare benefits to cover home health care, vision and hearing — all Sanders hobbyhorses.

It’s “an important step forward,” Sanders allows. But in interviews and speeches, he tends to focus more on Trump’s negatives than Harris’s positives.

Meanwhile, he’s crisscrossing the nation weeks before the election, stumping for local candidates and measures and urging voters to keep Trump out of the White House — rather than shepherd his own Senate reelection bid, where he’s a shoo-in.

“I am here for a fairly simple reason: This election is probably the most consequential election in the modern history of the United States of America,” Sanders tells a packed crowd in Wisconsin, a message he repeats at rallies in Michigan, Texas and other states.

Bernie Sanders is running on behalf of the Democratic Party. And he doesn’t have any time to waste.

Sitting in his committee hearing room in July, Sanders reflected on why he's running for reelection, even as peers such as Biden are beginning to step back. “This country is at a pivotal moment in American history,” Sanders said. “The issues are so significant, and I have a role to play.” (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)

Written by Dan Diamond ... Dan Diamond is a national health reporter for The Washington Post. He joined The Post in 2021 after five years at Politico, where he won a George Polk award for investigating the Trump administration's response to the coronavirus pandemic.follow on X @ddiamond