Date: 2026-02-17 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00012652

The Trump Adminstration

Policy and Perception

The God of Carnage ... Donald Trump has already demonstrated his determination to demolish his predecessors’ legacy – and not only at home. If one thing has become abundantly clear, it is that the world order he leaves behind will not be one in which America is first.

Policy and Perception

The God of Carnage ... Donald Trump has already demonstrated his determination to demolish his predecessors’ legacy – and not only at home. If one thing has become abundantly clear, it is that the world order he leaves behind will not be one in which America is first.

Getty Images

Original article: https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/the-god-of-carnage-2017-01

Peter Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

In his first week in office, US President Donald Trump has begun wreaking havoc on the post-1945 world. Joschka Fischer, Nina Khrushcheva, Joseph Nye, and other Project Syndicate contributors navigate the emerging international disorder.

JAN 27, 2017

Donald Trump has already demonstrated his determination to demolish his predecessors’ legacy – and not only at home. If one thing has become abundantly clear, it is that the world order he leaves behind will not be one in which America is first.

The Apocalypse didn’t arrive with Donald Trump’s inauguration as US president, but the rhetoric of divine wrath surely did. Rather than adopt the soothing or soaring cadences of Washington, Lincoln, Franklin Roosevelt, Kennedy, or Reagan, Trump’s inaugural address invoked “carnage,” “God’s people,” and the “righteous public.” He sounded less like Andrew Jackson, the 1830s populist US president to whom his supporters compare him, than the Puritan theologian Jonathan Edwards preaching his terrifying sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.”

For Trump, of course, the “sinners” are not the adulterers and idlers Parson Edwards had in mind. They are the businesses, domestic opponents, and foreign leaders who have rejected “America first.” They are, in short, the “establishment,” much of which was in the congregation. As four of Trump’s five living predecessors – Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama – looked on, he defined their legacy as one of unmitigated greed, self-dealing, and corruption by an entrenched Washington elite that had immiserated ordinary Americans and brought the US to the brink of ruin.

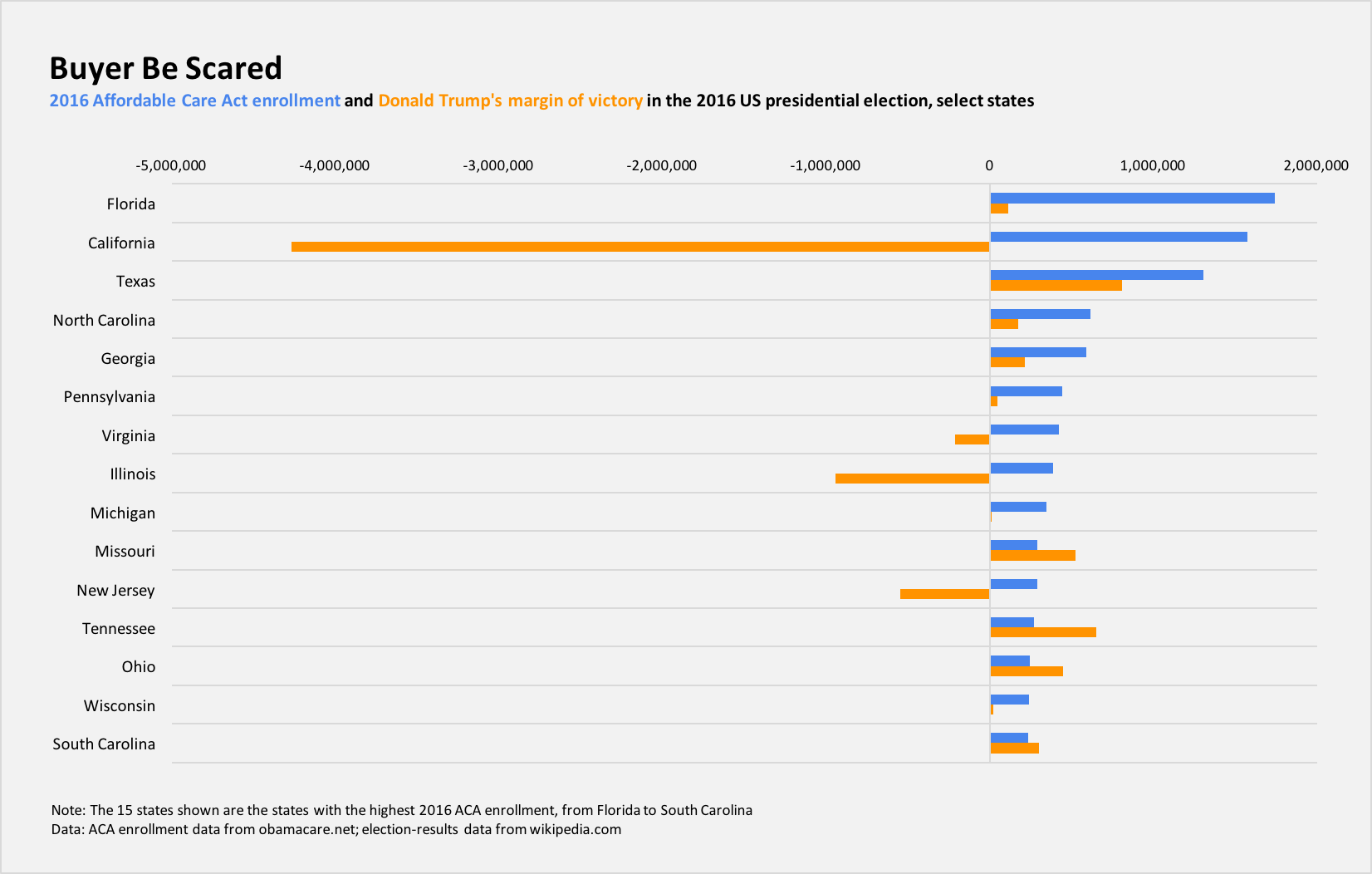

This was no mere continuation of Trump’s incendiary campaign rhetoric. He immediately began eviscerating his predecessors’ policy legacy. His first executive order took aim at Obama’s Affordable Care Act, threatening to leave 18 million Americans without health insurance within a year (and possibly wreaking havoc on many of his own voters - see chart). In the following days, he signed orders to withdraw the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP); revive oil pipeline projects halted by Obama; construct a wall on the border with Mexico; and cut funding for family planning in developing countries. He also moved to boost a deportation force to round up undocumented immigrants, and has mooted the possibility of reviving secret detention sites and the torture of terrorism suspects. He’s even proposed reversing US efforts to combat AIDS in Africa (a George W. Bush initiative).

ACA enrollment chart

And Trump is not only keeping his promises. He’s also keeping his lies. The Orwellian term “alternative facts” quickly entered America’s political lexicon following his first full day in office, when Trump and his top advisers, channeling the spirit of Chico Marx, chastised journalists for believing their own eyes about the size of the crowd at his inauguration. On the second day, he repeated to congressional leaders his post-election lie that millions of illegal voters had denied him a popular majority by backing his opponent, Hillary Clinton – and called for an official investigation of “voting fraud” that even his own lawyers have said, in court filings, did not occur.

Trump and his Republican congressional backers are taking steps to police far more important “facts,” by escalating what he calls his “running war with the media,” and, more ominously, by barring government agencies from communicating with the public – or even gathering data – about climate change, housing discrimination, and much else. He appears determined to use presidential power to elevate “truthful hyperbole” – the credo he touted in his 1987 memoir The Art of the Deal – into a governing ethos.

But turning mendacity into national policy is a formula for creating, not halting, “carnage” – and not just at home. After all, in a crisis, what sane world leader would take Trump’s word?

Project Syndicate commentators suggest that anticipating and mitigating the Trump administration’s disruptive impact worldwide is now the central question of our time. But one fundamentally important outcome, they suggest, is already certain: in the world order that Trump leaves behind, America will not be first. Anti-Global America

“America first,” points out Princeton University historian Harold James, is an idea with an old – and disturbing – pedigree. “The nationalist thrust of Trump’s inaugural address,” James observes, “echoed the isolationism championed by the racist aviator Charles Lindbergh, who, as a spokesman for the America First Committee, lobbied to keep the US out of World War II.” Likewise, Trump’s speech “renounced the country’s historical role in creating and sustaining the post-war order.” While his “objection to ‘global America’ is not new,” James rightly emphasizes, “hearing it from a US president certainly is.”

Former German foreign minister Joschka Fischer and former Spanish foreign minister Ana Palacio are alarmed by this vision’s likely global impact. “‘America first,’” says Fischer, “signals the renunciation, and possible destruction, of the US-led world order that Democratic and Republican presidents, starting with Franklin D. Roosevelt, have built up and maintained – albeit with varying degrees of success – for more than seven decades.” As Palacio puts it, by proclaiming a “right of all nations to put their own interests first,” Trump wants to “turn back the clock” on the post-war “rules-based system.” His vision, she argues, implies a reversion to a “nineteenth-century spheres of influence” model of world order, “with major players such as the US, Russia, China, and, yes, Germany, each dominating their respective domains within an increasingly balkanized international system.”

Richard Haass, President of the Council on Foreign Relations in New York, agrees. Trump’s worldview, says Haass, is “largely inconsistent” with the international cooperation that is needed nowadays to address the world’s most pressing problems. If Trump’s “America first” doctrine “remains the US approach,” he argues, “progress toward building the sort of order that today’s interconnected world demands will come about only if other major powers push it – or it will have to wait for Trump’s successor.” But this outcome “would be second best, and it would leave the United States and the rest of the world worse off.”

May Day for the Special Relationship

The potential for harm to vital US relationships has already become apparent, with Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto abruptly canceling an official visit in the wake of Trump’s order to begin construction of the border wall. On the other hand, British Prime Minister Theresa May, the first foreign leader to meet with Trump in the White House, seems intent on cementing ties with the new administration.

As Dominique Moisi of the Institut Montaigne in Paris notes, beyond their shared “distrust of Europe,” they make an odd couple. May “believes in free trade and is suspicious of Russia, while Trump is calling for protectionism and wants to forge a special partnership” with the Kremlin. And yet, in embracing a clean break from the European Union since last June’s Brexit referendum, May, too, “seems to be driven by domestic politics to prioritize national sovereignty over the economy.” In fact, “her argument to the British people is not unlike what Russian President Vladimir Putin tells his own citizens: no one lives by bread alone, and recovering sovereignty and national greatness is worth the economic risk.”

Philippe Legrain, a former economic adviser to the EU Commission President, is not surprised by May’s choice of “a Brexit variant whereby Britain leaves both the EU’s single market and its customs union” – and not just because “she knows little, and cares even less, about economics.” Like Moisi, Legrain believes that May’s “ultimate objective is to survive as Prime Minister.” From her perspective, “controlling immigration – a long time personal obsession – will endear her to ‘Leave’ voters,” while “ending the European Court of Justice’s jurisdiction in Britain will pacify the nationalists in her Conservative Party.” That such a stance jibes with Trump’s nationalist worldview seems to have provided even more incentive for May to abandon the EU after more than four decades.

“May claims that Brexit will enable Britain to strike better trade deals with non-EU countries,” Legrain continues, “and she is pinning her hopes on a quick deal with Trump’s America.” But he believes she is in for a rude awakening: given Britain’s “desperate negotiating position, even an administration headed by Hillary Clinton would have driven a hard bargain on behalf of American industry.” As he points out, “US pharmaceutical companies, for example, want the UK’s cash-strapped National Health Service to pay more for drugs.” More broadly, the mere fact that “[l]ike China and Germany, Britain exports much more to America than it imports from the US” will weaken May’s hand. “Trump hates such ‘unfair’ trade deficits,” Legrain notes, “and has pledged to eliminate them.”

Former Belgian Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt, wonders “if the UK’s pursuit of a bilateral deal with the US is just about economics, or if it implies a broader shift in British foreign policy.” Indeed, Verhofstadt, who will be the European Parliament’s lead Brexit negotiator once May formally triggers the withdrawal process (most likely in March), suggests that “Trump’s Euroskeptic team are influencing” her approach. By staking “her own country’s future on an alliance with an unpopular, untested, and mendacious American president,” he says, “May’s government is playing a dangerous and shortsighted game.” After all, “[t]he vast majority of the UK’s trade is with the EU, not with the US; and this, like the UK’s geographical location and security environment, is not going to change.”

Pulling Down the Pillars of Peace

On the latter point – the defense of the world’s democracies – Verhofstadt, like other Project Syndicate commentators, is unequivocal. “[N]ow that Trump’s presidency has cast doubt on US security guarantees,” he says, “the UK and the EU should be forging a strategic partnership to ensure European security” and “must defend and promote liberal democratic values globally, not embrace populists’ narcissistic nationalism.” Iain Conn, CEO of Centrica (the parent company of British Gas), similarly believes that “it is more important than ever that the developed democracies come together,” not only to address current and future global problems, as Haass suggests, but to preserve their security. “We must protect the ties that bind,” Conn argues, “and place our hope for the future in our alliances and shared traditions.”

The question is whether the world’s democracies can deepen their ties while struggling to manage the crises that are more likely to erupt in the absence of US leadership. Fischer believes that Germany and Japan “will be among the biggest losers if the US abdicates its global role under Trump.” Since their “total defeat in 1945,” he notes, both countries “have rejected all forms of the Machtstaat, or ‘power state,’” embracing their role as “active participants in the US-led international system.” But their ability to reinvent and sustain themselves as peaceful trading countries has always been premised on “the US security umbrella.”

Should that umbrella be removed, Fischer continues, “Japan’s peripheral geopolitical position might, theoretically, allow it to re-nationalize its own defense capacities,” though this “could significantly increase the likelihood of a military confrontation in East Asia” – a particularly frightening scenario, “given that multiple countries in the region have nuclear weapons.” But, in contrast to Japan, “Germany cannot re-nationalize its security policy even in theory, because such a step would undermine the principle of collective defense in Europe.” And, as Fischer reminds us, that principle, by integrating “former enemy powers so that they posed no danger to one another,” has been fundamental to peace in Europe.

It is not only post-war security arrangements that are at stake. Trump has called into question the two greatest diplomatic achievements of recent years: the Iran nuclear accord and the Paris climate agreement. “If the US withdraws from, or fails to comply with, either deal,” says Javier Solana, a former NATO secretary general and EU High Representative for foreign affairs, “it will strike a heavy blow to a global-governance system that relies on multilateral agreements to resolve international problems.”

For Haass, “cooperation on climate change” may be “the quintessential manifestation of globalization, because all countries are exposed to its effects, regardless of their contribution to it.” The Paris accord, “in which governments agreed to limit their emissions and to provide resources to help poorer countries adapt,” says Haass, “was a step in the right direction.”

But the unraveling of the Iran nuclear deal, officially known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), poses the most immediate danger. The “International Atomic Energy Agency,” Solana notes, says that the Iranian authorities have permitted it “to inspect every site that the agency has requested to see – including those from which it was barred before the agreement – and has granted inspectors access to its electronic systems and chain of enrichment.” Solana quotes a report by the International Crisis Group: “Trump is the first US president in more than two decades who enters office not needing to worry about Iran crossing the threshold to nuclear weaponization undetected.”

But that conclusion, however well founded and widely shared, will not necessarily withstand the Trump administration’s “alternative facts.” In that case, Solana argues, US withdrawal from the JCPOA, rather than “contributing to regional stability,” would risk bringing about “an even greater nightmare” in the Middle East. Already, he notes, “Saudi Arabia would like to end its military intervention in Yemen,” while “Iran is commencing a presidential election campaign” and “Turkey is seeking an outcome to the Syrian conflict that aligns with its own policy toward the Kurds.” Meanwhile, “Russia needs to withdraw its troops from Syria – an intervention that has been bleeding its economy.” All of these actors, as well as the EU – which, as Solana points out, “still needs to resolve the refugee crisis” – would be destabilized by the effects of nuclear uncertainty, and the possibility of an arms race, in the Middle East. Moscow on the Potomac?

Perhaps the one foreign policy issue where Trump’s instincts may prove correct, if for the wrong reasons, is the US relationship with Russia, which he is determined to improve. Robert Harvey, an author and former UK Member of Parliament, notes that “Russia has generally upheld its arms-control agreements with the US,” and that it lacks “the economic and industrial might to sustain any long-term war effort.” Nonetheless, he is skeptical. “George W. Bush and former British Prime Minister Tony Blair initially saw Putin as a man with whom they could do business,” he notes. “But, now in power for 17 years, Putin has shown himself to be a venal and violent leader,” who “has reverted to Cold War tactics against domestic dissidents and foreign targets.”

Yet the New School’s Nina Khrushcheva, no Putin apologist, thinks that Trump might nonetheless stumble into the right policy. Putin’s “immediate goal is to expose the West’s double standards,” Khrushcheva argues, offering several examples, “thereby breaking down Western barriers to his pursuit of Russian interests.” And she hopes that Trump’s obvious affinity for Putin will somehow lead the US to “devise a sound, thoughtful, and measured approach toward Russia – one that appeals to values not as propaganda, but as the basis of a more straightforward and credible foreign policy.”

Like Harvey and Khrushcheva, the economic historian Robert Skidelsky focuses on the impact on Russia of NATO’s eastward expansion into Central Europe and the ex-Soviet Baltic states. Skidelsky, too, is highly critical of the Putin regime’s “human-rights abuses, assassinations, dirty tricks, and criminal prosecutions to intimidate political opponents.” Nonetheless, he believes that “today’s anti-liberal, authoritarian Russia is as much a product of the souring of relations with the West as it is of Russian history or the threat of disintegration that Russia faced in the 1990s.”

Skidelsky borrows an argument from the Russian analyst Dmitri Trenin. “The West,” he says, “should fear Russia’s weakness more than its imperial designs.” Harvey, too, believes that “Russia’s position today is even less secure than it was in the 1980s, when the Soviet Union’s weakening economy could no longer sustain control of an Eastern European buffer and satellites elsewhere.” But whereas Harvey believes that “[s]ooner rather than later, Putin’s economic incompetence will catch up with him,” and that the West should wait until it does, Skidelsky sees “no reason why a much better working relationship cannot be established.”

There are three reasons for this, according to Skidelsky. First, “Putin’s foreign-policy coups, while opportunistic, have been cautious.” Moreover, “[w]ith American power on the wane and China’s on the rise, a restructuring of international relations is inevitable,” and “Russia could play a constructive role in this revision, if it does not overestimate its strength.” And, echoing Harvey here as well, Skidelsky points out that “Russia has shown – on the nuclear deal with Iran and the elimination of Syria’s chemical weapons – that it can work with the US to advance common interests.”

But Carl Bildt, a former prime minister and foreign minister of Sweden, offers several reasons to be wary of any rapprochement with Russia. For starters, whereas Skidelsky sees in Putin a cautious leader, Bildt sees a shrewd one. “[W]henever opportunities present themselves,” Bildt observes, “the Kremlin is ready to use all means at its disposal to regain what it considers its own.” Even in the absence of “a firm and comprehensive plan for imperial restoration,” he says, Putin “undoubtedly has an abiding inclination to make imperial advances whenever the risk is bearable, as in Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014.”

Moreover, Khrushcheva and Skidelsky are wrong, Bildt suggests, to question the wisdom of NATO enlargement. “Expanding both NATO and the European Union to include the Central European and Baltic countries has been essential to European security,” he insists. “In any other scenario, we would probably already be locked in a profoundly dangerous power struggle with a revanchist Russia reclaiming what it had lost.” He believes that “Russia will come to terms with itself only if the West firmly supports these countries’ independence over a prolonged period of time.” In that case, “Russia will realize that it is in its own long-term interest to break its historical pattern, concentrate on its domestic development, and build peaceful and respectful relations with its neighbors.” China First

Perhaps the most dangerous foreign-policy reversal that Trump appears to be undertaking concerns the US stance toward China. Christopher Hill, a former US assistant secretary of state, points out that Trump seems “to have concluded that the best way to upend China’s strategic position was to subject all past conventions, including the ‘One China’ policy, to re-examination.” Similarly, Yale University’s Stephen Roach, a former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, believes that Trump is “contemplating a wide range of economic and political sanctions – from imposing punitive tariffs and designating China as a ‘currency manipulator’ to embracing Taiwan.”

Both Hill and Roach foresee strategic failure if the US pursues this approach. While the Trump administration’s “anti-China biases are without modern precedent,” Roach notes, its strategy “is based on the mistaken belief that a newly muscular United States has all the leverage in dealing with its presumed adversary, and that any Chinese response is hardly worth considering.” But, as Hill puts it, “China is not a subcontractor on a construction project, and it has means at its disposal to apply its own pressure on the new US administration.”

Roach spells it out: if the US “follows through with its threats, expect China to reciprocate with sanctions on US companies operating there, and ultimately with tariffs on US imports – hardly trivial considerations for a growth-starved US economy.” China could also become “far less interested in buying Treasury debt – a potentially serious problem, given the expanded federal budget deficits that are likely under Trumponomics.”

Even barring such outcomes, Trump, it seems clear, has begun his tenure by disarming key instruments of US influence in Asia, namely those stemming from America’s post-war security guarantees and its stewardship of the multilateral institutions that have nurtured global economic openness. And, given his protectionism and renunciation of the TPP, China is likely to end up with the regional hegemony that successive US presidents – Republicans and Democrats alike – have opposed.

Global leadership may not be far behind. As Palacio notes, Chinese President Xi Jinping, who addressed the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos for the first time earlier this month, is “now the default champion of globalization.” Daniel Silke, a South African political strategist, goes even further. Already, “China’s rise has provided a new orbit for many countries around the world – particularly developing and emerging economies,” Silke observes, and its “exceptional diplomatic skill across the African continent (and, increasingly, Southeast Asia) has made it an alternative hegemonic force.” As the US disengages and squanders its soft power (for example, by cutting development aid), China will gain “new opportunities to cement its role as a provider of investment and all manner of infrastructure and assistance to a host of countries eager to develop.”

But, whereas Silke sees a China that is “eager to find a soft-power niche in which it can gain a foothold of goodwill,” the Indian strategist Brahma Chellaney sees only the froideur of strategic realism. China’s leaders have become extremely adept at “the use of economic tools to advance their country’s geostrategic interests,” Chellaney argues, in order “to fashion a hegemonic Sinosphere of trade, communication, transportation, and security links.” To do so, the Chinese government is ingeniously “integrating its foreign, economic, and security policies.” If strategically important developing countries “are saddled states with onerous debt as a result, their financial woes only aid China’s neocolonial designs.” Pax Asiana?

What, if anything, can Asian countries do to resist China’s hegemonic designs at a time when Trump is calling into question US commitments across the region? New America’s Anne-Marie Slaughter and Mira Rapp-Hooper of the Center for a New American Security offer a sobering analysis. “Many Asian countries, through deep and predictable political engagement with the US, have grown accustomed to America’s commitment to their security,” they point out. “And, in contrast to multilateral security arrangements like NATO, America’s Asian alliances are founded on individual bilateral pacts,” which leaves them “particularly vulnerable to Trump’s vicissitudes.” Fake news or real views LEARN MORE

But, instead of “falling into despair,” Slaughter and Rapp-Hooper continue, “America’s Asian allies should take matters into their own hands and start networking.” Creating a resilient regional security architecture has never before been a high priority, precisely owing to those bilateral US security guarantees. “By building and institutionalizing ties among themselves,” Slaughter and Rapp-Hooper argue, “US allies in Asia can reshape their regional security network from a US-centric star to a mesh-like pattern, in which they are as connected to one another as they are to the US.” That would give them “a system [that] can strengthen stability for unsteady times.”

But it would also be a long-term endeavor. In the near term, Asia’s stability will be in the hands of Trump, who, according to Harvard’s Joseph Nye, should be “wary of two major traps that history has set for him.” One is the so-called Thucydides Trap, named for the ancient Greek historian of the Peloponnesian War, who warned that “cataclysmic war can erupt if an established power (like the United States) becomes too fearful of a rising power (like China).” The other, Nye says, is the “Kindleberger Trap,” named for Charles Kindleberger, who “argued that the disastrous decade of the 1930s was caused when the US replaced Britain as the largest global power but failed to take on Britain’s role in providing global public goods.”

In other words, rather than being too strong, China may be too weak for global leadership. “If pressed and isolated by Trump’s policy,” Nye asks, “will China become a disruptive free rider that pushes the world into a Kindleberger Trap?” In the 1930s, the trap – caused by US free riding – contributed to “the collapse of the global system into depression, genocide, and world war,” he notes.

So, one problem for the world today is that Trump “must worry about a China that is simultaneously too weak and too strong.” But another, perhaps more serious concern, stems from the fact that, given Trump’s willful ignorance and incorrigible indiscipline, neither the Thucydides Trap nor the Kindleberger Trap may matter in the end. As Nye acknowledges, wars often are “caused not by impersonal forces, but by bad decisions in difficult circumstances.” In order to circumvent strategic traps, Nye concludes, Trump “must avoid the miscalculations, misperceptions, and rash judgments that plague human history.”

Is Trump really capable of that? Judging from his first six days in office, his presidency itself appears to be a long parade of such human shortcomings. And on the seventh day, he is unlikely to rest.