OVERVIEW

MANAGEMENT

PERFORMANCE

POSSIBILITIES

CAPITALS

ACTIVITIES

ACTORS

BURGESS

|

ECONOMICS

CRITIQUE OF NOBEL PRIZE CHOICES Bernanke v. Kindleberger: Which Credit Channel?

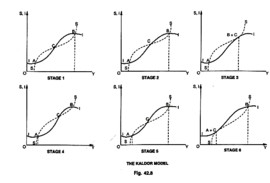

Original article: https://www.ineteconomics.org/perspectives/blog/bernanke-v-kindleberger-which-credit-channel Peter Burgess COMMENTARY This is a delightful piece ... right up my memory lane. The following is an extract from the comments associated with this article: G.Visakh Varma • 6 days agoPerry Mehrling has reminded me of my days as an economics student at Cambridge where the shadow of Keynes was everywhere and some important Keynes acolytes from the 1930s like Joan Robinson and Nicholas Kaldor and others were carrying the torch. One of my takeaways from my time at Cambridge was that Keynes was constantly striving better to understand what was actually going on with society and the economy ... and wanted policy to be the best it could possibly be given what we knew (or did not know) about its behavior. I am afraid I had not realized until today that some of the work that Nicholas Kaldor was doing while he was at Cambridge has something in common with what I am trying to do 60+ years later. When I looked at Kaldor's Wikipedia page I was taken by the image shown at the end of this webpage. Specifically, the idea that there are multiple drivers of economic change, not one single driver. This should be pretty obvious ... and I was very much aware of it when I was working on engineering and technical problems, but when it came to economics, one of the biggest and complex 'systems' that there is, the assumption are usually unbelievable simplistics and it is no wonder that the results are rarely of much 'real world' value. The more I look at the writing of people who claim to know something about economics, banking and finance, I am surprised at how little I tend to agree with. The people with actual experience are usually writing about the little bubble where they work without knowing much about the massive amount of economic activity going on outside their bubble, and the people who write about the big picture have usually not much experience of how all the real-world decisions are getting made all the time in real-time. Peter Burgess | ||

|

Bernanke v. Kindleberger: Which Credit Channel?

By Perry G. Mehrling OCT 13, 2022 | MACROECONOMICS In the papers of economist Charles Kindleberger, Perry Mehrling found notes on the paper that won Ben Bernanke his Nobel Prize. In the 1983 paper cited as the basis for Bernanke’s Nobel award, the first footnote states: “I have received useful comments from too many people to list here by name, but I am grateful to each of them.” One of those unnamed commenters was Charles P. Kindleberger, who taught at MIT full-time until mandatory retirement in 1976 and then half-time for another five years. Bernanke himself earned his MIT Ph.D. in 1979, whereupon he shifted to Stanford as Assistant Professor. Thus it was natural for him to send his paper to Kindleberger for comment, and perhaps also natural for Kindleberger to respond. As it happens, the carbon copy of that letter has been preserved in the Kindleberger Papers at MIT, and that copy is reproduced below as possibly of contemporary interest. All footnotes are mine, referencing the specific passages of the published paper, a draft copy of which Kindleberger is apparently addressing, and filling in context that would have been familiar to both Bernanke and Kindleberger but may not be to a modern reader. With these explanatory notes, the text speaks for itself and requires no further commentary from me. --------------------------- “May 1, 1982 Dr. Ben Bernanke Graduate School of Business, Stanford University. Stanford, CA 94305 Dear Dr. Bernanke, Thank you for sending me your paper on the great depression. You ask for comments, and I assume this is not merely ceremonial. I am afraid you will not in fact welcome them. I think you have provided a most ingenious solution to a non-problem.[1] The necessity to demonstrate that financial crisis can be deleterious to production arises only in the scholastic precincts of the Chicago school with what Reder called in the last JEL its tight priors, or TP.[2] If one believes in rational expectations, a natural rate of unemployment, efficient markets, exchange rates continuously at purchasing power parities, there is not much that can be explained about business cycles or financial crises. For a Chicagoan, you are courageous to depart from the assumption of complete markets.[3] You wave away Minsky and me for departing from rational assumptions.[4] Would you not accept that it is possible for each participant in a market to be rational but for the market as a whole to be irrational because of the fallacy of composition? If not, how can you explain chain letters, betting on lotteries, panics in burning theatres, stock market and commodity bubbles as the Hunts in silver, the world in gold, etc… Assume that the bootblack, waiters, office boys etc of 1929 were rational and Paul Warburg who said the market was too high in February 1929 was not entitled to such an opinion. Each person hoping to get in an[d] out in time may be rational, but not all can accomplish it. Your data are most interesting and useful. It was not Temin who pointed to the spread (your DIF) between governts [sic] and Baa bond yields, but Friedman and Schwartz.[5] Column 4 also interests me for its behavior in 1929. It would be interesting to disaggregate between loans on securities on the one hand and loans and discounts on the other. Your rejection of money illusion (on the ground of rationality) throws out any role for price changes. I think this is a mistake on account at least of lags and dynamics. No one of the Chicago stripe pays attention to the sharp drop in commodity prices in the last quarter of 1929, caused by the banks, in their concern over loans on securities, to finance commodities sold in New York on consignment (and auto loans).[6] This put the pressure on banks in areas with loans on commodities. The gainers from the price declines were slow in realizing their increases. The banks of the losers failed. Those of the ultimate winners did not expand. Note, too, the increase in failures, the decrease in credit and the rise in DIF in the last four of five months of 1931.[7] Much of this, after September 21, was the consequence of the appreciation of the dollar from $4.86 to $3.25.[8] Your international section takes no account of this because prices don’t count in your analysis. In The World in Depression, 1929-1939, which you do not list,[9] I make much of this structural deflation, the mirror analogue of structural inflation today from core inflation and the oil shock. But your priors do not permit you to think them of any importance. Sincerely yours, [Charles P. Kindleberger]” References

Academic Council Professor of Economics, Boston University

Shifting, multiple equilibria lead to six-stage business cycle in which the economy oscillates around optimal income growth and generates phases of boom and bust. See Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicholas_Kaldor

| The text being discussed is available at | https://www.ineteconomics.org/perspectives/blog/bernanke-v-kindleberger-which-credit-channel and |