OVERVIEW

MANAGEMENT

PERFORMANCE

POSSIBILITIES

CAPITALS

ACTIVITIES

ACTORS

BURGESS

|

THE US ECONOMY

POVERTY AND INEQUALITY CBPP ... A Guide to Statistics on Historical Trends in Income Inequality

FIGURE 1: Income Gains Widely Shared in Early Postwar Decades - But Not Since Then https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/a-guide-to-statistics-on-historical-trends-in-income-inequality PDF of this report (22 pp.) ... CBPP-2020-Poverty-and-Inequality-22879.pdf Peter Burgess COMMENTARY This POLICY FUTURES report from January 2020 on the statistics of income inequality is valuable reading. It would be good if this was required reading for most of the media hosts and moderators who are charged with anything to do with reporting economics. There has been plenty of economic and statistical data about growing inequaiity for a long time ... certainly from the 1990s and to some extent even before this. One has to wonder why the issue of growing inequality has been off the news agenda and ignored so completely. Some part of the answer has to be the manner in which the media is now structured with news effectively censored by the 'owners' of news organizations and a fear that reporting the uncomfortable truths about the economy and society ... and now the environment as well ... that will cut off funding because the owners and related 'fat cats' don't like the subject. I became aware of growing inequality in the US economy about 30 years ago around the time of Reagan's Savings and Loan Crisis and the growing focus on financial performance with everything else ignored. In the 1980s corporate profits started to recover in large part because US manfactruring was being shuttered and production outsourced to lower cost countries mainly in Asia. I am appalled and very disappointed that the idea of getting corporate management to optimize for the 'Triple Bottom Line' (People, Planet, Profit) which did get much traction after it was promoted around 1995. It would have made a big difference, but we still remain firmly in the grip of managing for profit maximization more than 25 years later. I refer to thie as out of control financialization of the modern world ... promoted aggressively by the best known business schools and implemented equally aggressively by the big banks and financial institutions everywhere. Maybe stupid ... but who cares when investors are making wealth ... nothing like it since the golden age of the 1920s !!!!!!!!! Peter Burgess | ||

|

THE US ECONOMY ... POVERTY AND INEQUALITY

A Guide to Statistics on Historical Trends in Income Inequality BY CHAD STONE, DANILO TRISI, ARLOC SHERMAN AND JENNIFER BELTRÁN UPDATED JANUARY 13, 2020 (ACCESSED AUGUST 2022) The broad facts of income inequality over the past seven decades are easily summarized:

Data from a variety of sources contribute to this broad picture of strong growth and shared prosperity for the early postwar period, followed by slower growth and growing inequality since the 1970s. Within these broad trends, however, different data tell slightly different parts of the story, and no single data source is best for all purposes. This guide consists of four sections. The first describes the commonly used sources and statistics on income and discusses their relative strengths and limitations in understanding trends in income and inequality. The second provides an overview of the trends revealed in those key data sources. The third and fourth sections supply additional information on wealth, which complements the income data as a measure of how the most well-off Americans are doing, and poverty, which measures how the least well-off Americans are doing.

I. The Census Survey and IRS Income Data

The most widely used sources of data and statistics on household income and its distribution are the annual household survey conducted as part of the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS) and the Internal Revenue Service’s (IRS) Statistics of Income (SOI) data compiled from a large sample of individual income tax returns. The Census Bureau publishes annual reports on income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States based on the CPS data,[1] and the IRS publishes an annual report on individual income tax returns based on the SOI.[2] While the Federal Reserve also collects income data in its triennial Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF),[3] the SCF is more valuable as the best source of survey data on wealth. Each agency produces its own tables and statistics and makes a public-use file of the underlying data available to other researchers. In addition, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has developed a model that combines CPS and SOI data to estimate household income both before and after taxes, as well as average taxes paid by income group back to 1979.[4] Economists Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez have used SOI data to construct estimates of the concentration of income at the top of the distribution back to 1913.[5] More recently, they and their colleague Gabriel Zucman have expanded that work to examine trends in wealth concentration and to incorporate the portion of national income not captured in the tax or survey data into their analysis of income inequality.[6] CBO and Piketty, Saez, and Zucman regularly release reports incorporating the latest available data. Concepts of Income Measured in Census and IRS Data Census Money Income The Census Bureau bases its report on income and poverty on a sample of about 68,300 interviews[7] conducted through the Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) to the monthly CPS, which is the primary source of data for estimating the unemployment rate and other household employment statistics.[8] The ASEC, also called the March CPS,[9] provides information about the total annual resources available to families. These include income from earnings, dividends, and cash benefits (such as Social Security), as well as the value of tax credits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and non-cash benefits such as nutritional assistance, Medicare, Medicaid, public housing, and employer-provided fringe benefits. The income measure featured in the Census report is money income[10] before taxes, and the unit of analysis is the household. The latest data, for 2018, were released in September 2019. The statistics on household income are available back to 1967. Census has statistics on family income back to 1947, but because Census defines a “family” as two or more people living in a household who are related by birth, marriage, or adoption, those statistics exclude people who live alone or with others to whom they are not related. Census’s standard income statistics do not adjust for the size and composition of households. Two households with $40,000 of income rank at the same place on the distributional ladder, even if one is a couple with two children and one is a single individual. An alternative preferred by many analysts is to make an equivalence adjustment based on household size and composition so that the adjusted income of a single person with a $40,000 income is larger than the adjusted income of a family of four with the same income. Equivalence adjustment accounts for the fact that larger families need more total income but less per capita income than smaller families because they can share resources and take advantage of economies of scale. In recent reports, Census has supplemented its measures of income inequality based on household money income with estimates based on equivalence-adjusted income.[11] For reasons having to do with small sample size, data reporting and processing restrictions, and confidentiality considerations, Census provides more limited information about incomes at the very top of the income distribution than elsewhere in the distribution. For example, Census does not collect information about earnings over $1,099,999 for any given job; earnings above that level are recorded in Census data as $1,099,999.[12] Income Tax Data The income tax data used in distributional analysis come from a large sample of tax returns compiled by the IRS’s Statistics of Income Division. For 2017, the sample consisted of about 352,000 returns selected from the roughly 154 million returns filed that year.[13] For the population that files tax returns and for the categories of income that get reported, these administrative data are generally more accurate and more complete than survey data; the CPS, for example, is prone to underreporting of some kinds of income. However, not all people are required to file tax returns, and tax returns do not reflect all sources of income. Since those not required to file returns likely have limited incomes, tax data do not provide a representative view of low-income households. (This is the mirror image of the CPS’s inadequate coverage of high-income households.) Like Census money income, income reported on tax returns excludes non-cash benefits such as SNAP (formerly known as food stamps), housing subsidies, Medicare, Medicaid, and non-taxable employer-provided fringe benefits. The exclusion of non-filers is a major limitation of the tax data for distributional analysis. A further complication is that the data are available only for “tax-filing units,” not by household or family. (Members of the same family or household may file separate tax returns.) SOI tax data are also less timely than Census data. Final statistics for tax year 2017 were released in late 2019. Key Historical Series Constructed From Census and IRS Data CBO’s Distribution of Household Income CBO produces annual estimates of the distribution of household income and taxes that combine information from the CPS and the SOI.[14] Thus, these estimates have relatively detailed information about very high-income households and taxes paid (the strengths of the SOI) and about low-income households’ income and non-cash benefits (the strengths of the CPS). CBO also uses expanded measures of household income that include more sources of income than either CPS- or SOI-based measures alone. Over the years, CBO has made some significant changes to its methodology for analyzing the distribution of income and taxes, notably to how it values government-provided health insurance, which income measure it uses to rank households in analyzing the effects of transfers (government payments) and taxes on inequality, and how it adjusts for inflation (see the Appendix for more detail). In recent reports CBO employs three income measures:

CBO constructs its distributional tables by ranking individuals by their adjusted household income before transfers and taxes and dividing that ranking into five income groups (quintiles), each containing roughly an equal number of people (with further disaggregation of the top quintile).[15] The quintiles contain slightly different numbers of households, depending on the average household size at different points in the income distribution. One difficult issue in using an expanded definition of income, as CBO does, is how to treat government-provided health insurance such as Medicare and Medicaid. While it has not always done so, CBO now treats the average cost to the government of providing health insurance to eligible households as household income. It essentially does the same for employer-provided health insurance. While government-provided health insurance certainly increases a household’s well-being, it is not the same as money income or near-cash transfers like SNAP benefits because it does not directly help households of limited means meet basic needs such as food, clothing, and shelter.[16] Moreover, part of the government’s cost reflects administrative costs and health industry profits. Since medical benefits make up a sizeable and growing share of income in CBO’s series, this treatment of government-provided health insurance as equivalent to cash income can create differences between trends in CBO’s income data, which include these benefits, and trends in other income series that do not include these benefits, as discussed in Part II. The latest CBO report on the distribution of household income, released in July 2019, includes data for 1979-2016 on income before and after transfers and taxes as well as taxes paid for each quintile and for the top 1, 5, and 10 percent of households. Because of the effort involved in preparing these analyses, CBO’s annual updates tend to lag behind other sources of income data, often by a couple of years. Piketty-Saez Data on Income Concentration Economists Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez first published income inequality statistics in 2003 based on IRS data back to 1913 to provide a long-term perspective on trends in income concentration within the top 10 percent of the distribution.[17] They focused on the top of the income distribution because prior to World War II, only about 10 to 15 percent of potential tax units had to file an income tax return. Their income concept is market income before individual income taxes. They define market income as the sum of all income sources reported on tax returns, including realized capital gains[18] and taxable unemployment compensation.[19] Other non-taxable non-cash income sources, such as nutrition assistance and employer-provided health care benefits, are not included. People with market income who are not required to file income tax returns do not show up in the population of tax filers, and their income does not show up in the total income reported on tax returns.[20] Piketty and Saez address these omissions by estimating the number of non-filers and their income and adding these to the population of tax filers and the market income calculated from the income tax data.[21] They compute total income as all market income reported on tax returns plus their estimate of market income for non-filers.[22] The top 10 percent, top 1 percent, etc. are defined with respect to this total income and to the population of potential tax units (filers plus non-filers). Piketty and Saez do not make an adjustment for family size in their analysis. The primary advantage of these Piketty-Saez data is that they provide the longest historical series of annual data on income at the top of the distribution. The key limitation is that they are based exclusively on tax return data. As a result, they do not include data for individual non-filers (and therefore provide no information about the distribution of income among non-filers). Nor do they account for government cash transfers or public and private non-cash benefits. These public and private non-cash benefits, which are missing from the Piketty-Saez income measure, constitute a growing share of personal income.[23] As a result, the Piketty-Saez measure captures a declining share of personal income in the national income and product accounts over time, possibly distorting estimates of the share of total income growth occurring at the top of the distribution.[24] Recent work by Piketty, Saez, and Zucman tries to address this concern by ambitiously combining tax, survey, and national accounts data to estimate the distribution of total national income, both before and after transfers and taxes.[25] They allocate all national income to U.S. residents age 20 or older, with married couples’ income split equally in their base case.[26] As the authors acknowledge, however, “imputing all national income, taxes, transfers, and public goods spending requires making assumptions on a number of complex issues, such as the economic incidence of taxes and who benefits from government spending.”[27]

II. Broad Trends in Income Inequality

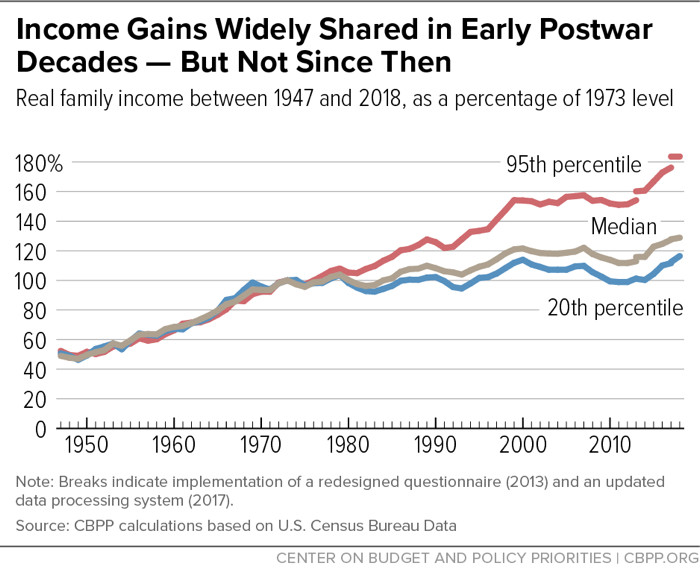

Because each individual source of readily available data on income distribution has different advantages and limitations, no single source illustrates all of the major trends in inequality over the past six decades or so. Ideally, we would look at a comprehensive measure of income that covers a long time span, allows us to compare income before and after transfers and taxes at different points in the distribution, and accounts for changes in household size and composition. CBO data satisfy many of these criteria but only go back to 1979 and are sensitive to particular methodological choices. (See the Appendix.) The historical Census family income data series and Piketty-Saez top-income concentration data cover a longer time span but use less comprehensive income measures and do not adjust for changes in household size and composition. Using a more comprehensive income measure, as Piketty, Saez, and Zucman do in their statistics on the distribution of national income, addresses some issues but raises others because of the number of assumptions involved. The Loss of Shared Prosperity Census family income data show that from the late 1940s to the early 1970s, incomes across the distribution grew at nearly the same pace. Figure 1 shows the level of real (inflation-adjusted) income at several points on the distribution relative to its 1973 level. [28] It shows that real family income roughly doubled from the late 1940s to the early 1970s at the 95th percentile (the income level separating the highest-income 5 percent of families from the remaining 95 percent), at the median (the income level separating the upper half of families from the lower half), and at the 20th percentile (the income level separating the bottom fifth of families from the remaining four-fifths). Then, beginning in the 1970s, income disparities began to widen, with income growing much faster at the top of the ladder than in the middle or bottom. Household (as opposed to family) income data, which are available only since 1967, show a similar pattern of widening inequality and scant growth in median income and income at the 20th percentile following the 1999 and 2007 business cycle peaks. While the Census family income data are useful for illustrating that income inequality began widening in the 1970s, other data are superior for assessing more recent trends.

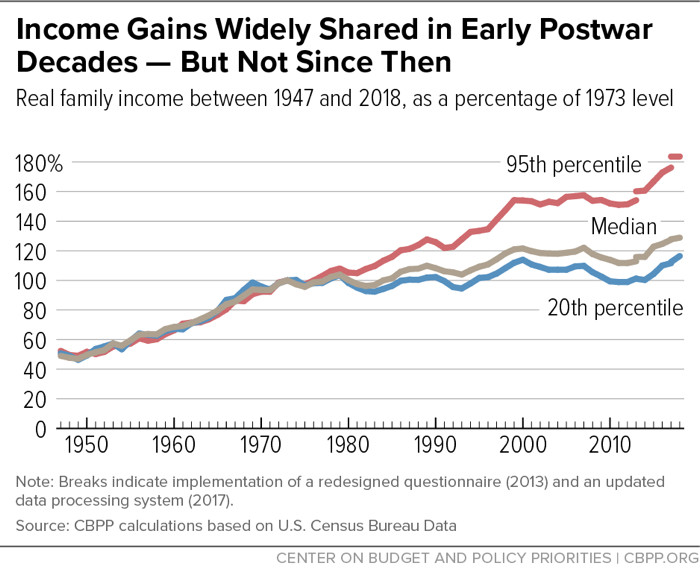

FIGURE 1: Income Gains Widely Shared in Early Postwar Decades - But Not Since Then Widening Inequality Since the 1970s Census family income data show that the era of shared prosperity ended in the 1970s and illustrate the divergence in income since then. CBO data allow us to look at what has happened to comprehensive income measures since 1979 — both before and after transfers and taxes — and offer a better view of what has happened at the top of the distribution. As Figure 2 shows, from 1979 to 2007 (just before the financial crisis and Great Recession), average income after transfers and taxes quadrupled for the top 1 percent of the distribution.[29] The increases were much smaller for the middle 60 percent and bottom 20 percent of the distribution. The CBO data also show income growth for the bottom 20 percent over this period that’s comparable to the 81st through 99th percentiles and substantially greater than the middle 60 percent. But this appears to be a methodological anomaly associated with CBO’s 2012 change in how it values government-provided health insurance and its 2018 change in the income measure used to rank households, as described in the Appendix. Together, these changes appear to strongly affect income trends for the poorest households, substantially raising the level and rate of growth of their measured income and perhaps substantially exaggerating the rise in low-income households’ true standard of living.

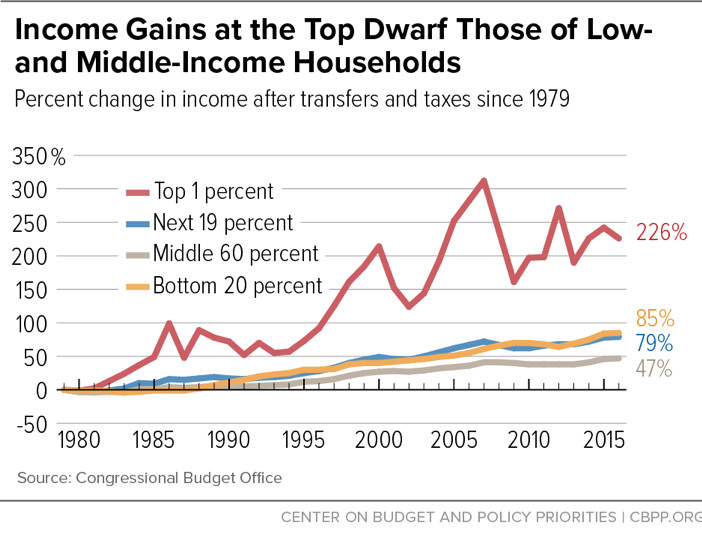

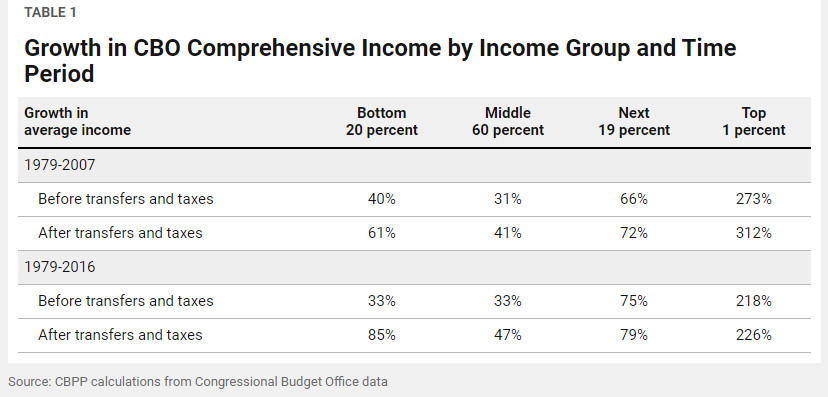

FIGURE 2: Income Gains at the Top Dwarf Those of Low- and Middle-Income Households After-tax incomes fell sharply at the top of the distribution in 2008 and 2009 but have since partially recovered. The up-and-down pattern in 2012-13 may reflect, in part, decisions by wealthy taxpayers to sell appreciated assets in 2012 in order to pay taxes on those capital gains before income tax rates increased in 2013. The Piketty-Saez data discussed below, which go through 2018, show a generally upward trend since 2009 that is consistent with this explanation. Although the average income after transfers and taxes of the top 1 percent of households remains well below its 2007 peak, the percentage increase in their average income after transfers and taxes from 1979 to 2016 was nearly five times that of the middle 60 percent and more than two-and-a-halftimes that of the bottom fifth. (See Table 1.) Moreover, CBO projects that the top 1 percent’s income after transfers and taxes will grow significantly faster than other income groups’ between 2016 and 2021, boosting its cumulative 1979-2021 growth to 281 percent.[30] This suggests that the Great Recession and financial crisis — like the dot-com collapse of the early 2000s — may have had only a temporary impact on the trend of faster income growth at the top.

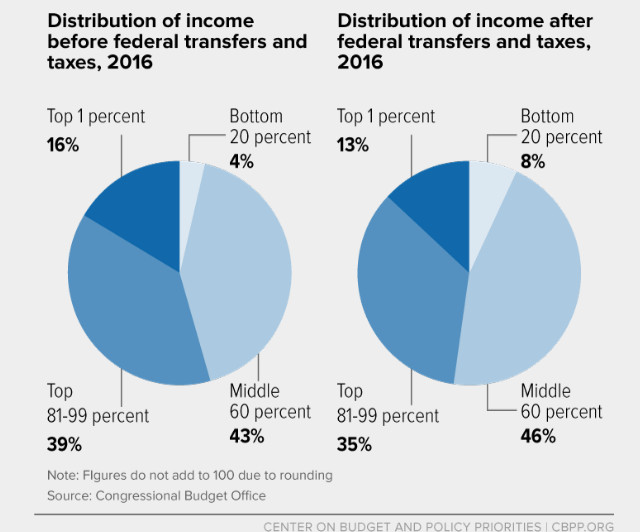

TABLE 1 ... Growth in CBO Comprehensive Income by Income Group and Time Period Trends in income before transfers and taxes look very similar. Because average tax rates have fallen for all income groups since 1979, income before transfers and taxes grew somewhat more slowly than income after transfers and taxes from 1979 to 2016. (See the box for more on the effect of transfers and taxes on income.) Transfers and Taxes Are Progressive, But Income Is Highly Concentrated Both Before and After Transfers and Taxes The charts below, using CBO data, show that the effect of transfers and taxes is progressive: the top 20 percent of households had a smaller share of total income in 2016 after transfers and taxes than before transfers and taxes, while the opposite is true for the other 80 percent of households. (Transfers include state and local government payments, but taxes do not include state and local taxes.)

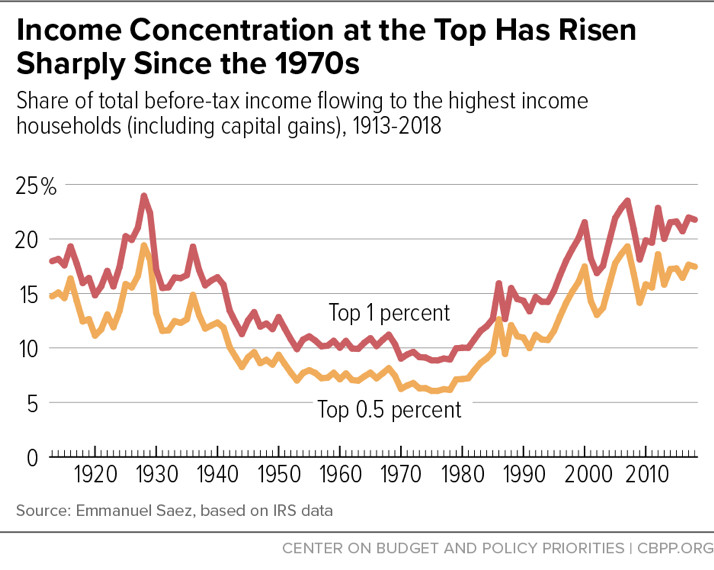

Chart: Distribution of income before and after federal transfers and taxes, 2016 Income is highly concentrated under either measure, however. The top 1 percent of households received 16 percent of income before transfers and taxes and 13 percent of income after transfers and taxes in 2016 — many times their share of the population. The comparable figures for the bottom 80 percent of households were 47 and 54 percent, respectively. As CBO’s latest analysis of trends in income distribution from 1979 to 2016 shows, both federal transfers and federal taxes reduce income inequality, but the reduction due to transfers is considerably larger. Income Concentration Has Returned to 1920s Levels The Piketty-Saez estimates derived from IRS tax data put the increasing concentration of income at the top of the distribution into a longer-term historical context.[31] As Figure 3 shows, the top 1 percent’s share of income before transfers and taxes has been rising since the late 1970s, and in recent decades has climbed to levels not seen since the 1920s. The vast majority of the increase occurred among the top 0.5 percent of households.[32] The increase in income concentration since the 1970s reversed the prior, long-term downward trend. After peaking in 1928, the share of income held by households at the very top of the income ladder declined through the 1930s and 1940s. Consistent with the shared prosperity found in the Census data on average family income, the share of income received by those at the very top changed little over the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s. The sharp rise in income concentration at the top since the late 1970s was interrupted briefly by the dot-com collapse in the early 2000s and again in 2008 with the onset of the financial crisis and Great Recession, but top incomes generally have been on the rise since 2009. The Piketty-Saez data show the same pattern in 2012-16 as CBO’s, with a further rise in top income shares in 2017.

FIGURE 3: Income Concentration at the Top Has Risen Sharply Since the 1970s

III. The Distribution of Wealth

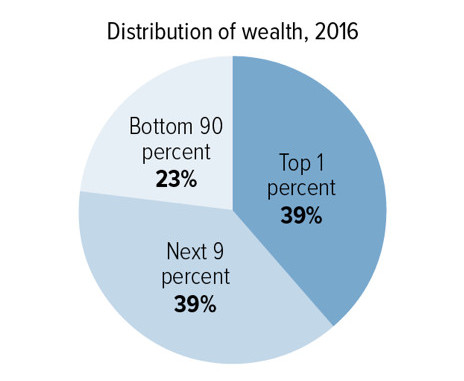

A family’s income is the flow of money coming in over the course of a year. Its wealth (sometimes referred to as “net worth”) is the total stock of assets it has as a result of inheritance and saving, less any liabilities.[33] Wealth is much more highly concentrated than income, and concentration at the top has risen since the 1980s.

Wealth Is Even More Concentrated Than Income

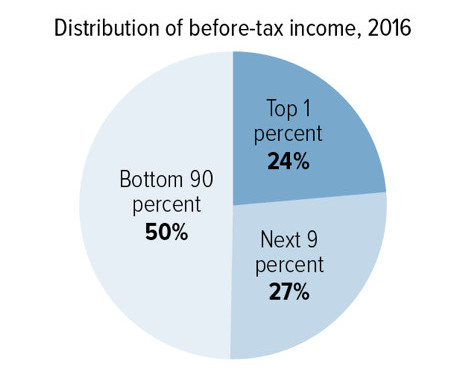

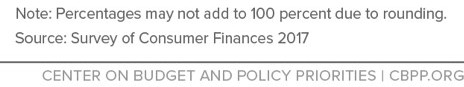

The main official source of data for the distribution of household wealth is the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), conducted every three years. SCF data go back to 1983; the latest published data are for 2016. The SCF is based on a sample of about 6,300 families. The data sources discussed in the preceding sections on income distribution are superior to the SCF for measuring income distribution, but none of those sources has comparable data for looking at the distribution of wealth. The latest SCF, for 2016, provides detailed statistics on wealth and income showing that wealth is much more concentrated than income.[34] (See Figure 4.) It should be noted that while there is considerable overlap, the top 1 percent of the income distribution does not contain exactly the same people as the top 1 percent of the wealth distribution. The SCF data show that the top 1 percent of the income distribution received roughly a quarter of all income in 2016, while the top 1 percent of the wealth distribution held nearly two-fifths of all wealth. Similarly, the top 10 percent of the income distribution received a little more than half of all income, while the top 10 percent of the wealth distribution held more than three-quarters of all wealth. SCF data show that the share of wealth held by the top 1 percent rose from just under 30 percent in 1989 to 38.6 percent in 2016, while the share held by the bottom 90 percent fell from 33.2 percent to 22.8 percent.[35] The Fed recently introduced distributional financial accounts that integrate the SCF’s rich distributional information with quarterly data on aggregate balance sheets of major sectors of the U.S. economy from the Fed’s Financial Accounts of the United States.[36] Distributional financial account data begin in 1989, are updated quarterly, and show the share of wealth held by the bottom 50 percent, next 40 percent, next 9 percent, and top 1 percent. The distributional financial accounts illustrate how little wealth the bottom 50 percent of households have (less than 2 percent) and how much the top 10 percent have (almost three-quarters). They also show that concentration has increased at the top of the wealth distribution since 1989.[37] (See Figure 5.)

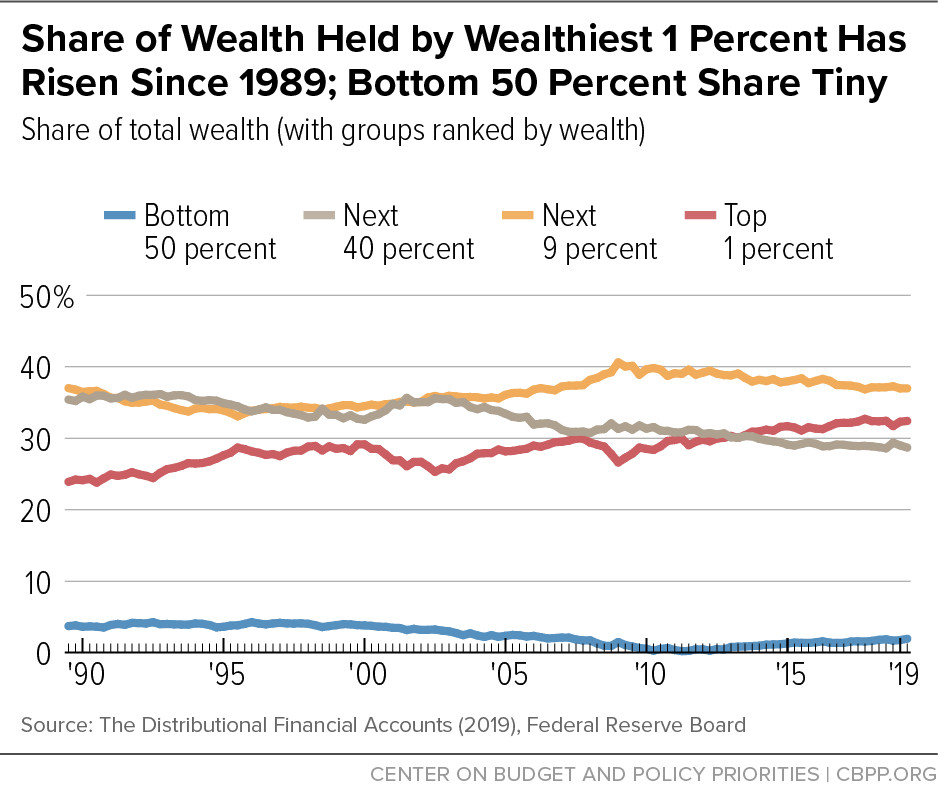

FIGURE 5: Share of Wealth Held by Wealthiest 1 Percent Has Risen Since 1989; Bottom 50 Percent Share Tiny While the Fed data are invaluable, they cover a relatively short period of time. Recently, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman have used tax-return information on income derived from wealth to infer the underlying distribution of wealth over time.[38] Figure 6 shows Saez and Zucman’s estimates of the share of wealth held by the top 1 percent and top 0.5 percent since 1913. As with income, these data show a long decline in wealth concentration from the late 1920s into the late 1970s but a marked increase since then, driven by a rising share of wealth at the very top (the top 0.5 percent).[39]

FIGURE 6: Wealth Concentration Has Been Rising Toward Early 20th Century Levels

IV. Poverty

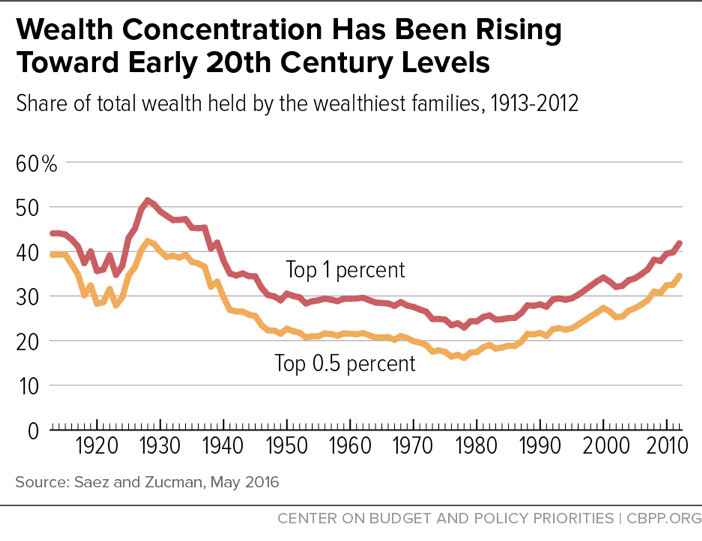

The Official Poverty Measure The official U.S. poverty measure was developed in the 1960s. The Census Bureau uses money income (as described above) to determine a person’s poverty status. Each family or unrelated individual in the population is assigned a money income threshold based on the size of their family and age of its members.[40] A person is defined as living in poverty if their family income is below the threshold for that family size and composition (the threshold for a couple with two children was about $25,500 in 2018). The poverty thresholds are adjusted each year to reflect changes in the consumer price index. The poverty rate is the percentage of people living in poverty. The official poverty statistics show a sharp decline in the poverty rate between 1959 and 1969 but little real change since then, apart from fluctuations due to the business cycle. For a number of reasons, however, the official measure is an unreliable guide to trends in poverty since 1970 and significantly understates progress in reducing poverty since then. It is based on Census money income, which includes cash assistance but does not count non-cash assistance like SNAP and rental vouchers. It also omits the impact of the tax system, including tax credits for working families like the EITC and Child Tax Credit. Alternatives to the Official Poverty Measure Over the years, researchers have raised a number of serious conceptual and measurement concerns about how the official poverty rate is calculated. Following the publication of an important National Academy of Sciences (NAS) report on poverty measurement in 1995,[41] the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) explored a number of experimental measures reflecting NAS recommendations. NAS-based measures use a more complete definition of income that includes non-cash benefits and tax credits while subtracting taxes and certain expenses. The NAS also recommended using a modernized poverty line that varies with local housing costs.[42] Census, with support from BLS, unveiled the newest refinement of the NAS-based measures, called the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), in 2011. This measure reflects recommendations from a federal interagency technical working group that drew on the NAS report and subsequent research. The Census SPM is available from 2009 to 2018.[43] Unlike the official measure, which counts only a family’s cash income, the SPM counts non-cash benefits (SNAP, housing assistance, WIC,[44] school lunch, and home energy assistance) and tax credits (the EITC and Child Tax Credit) as income and subtracts various expenses, namely federal and state income and payroll taxes, child care and other work expenses, out-of-pocket medical expenditures, and child support paid. In addition, it updates the poverty line each year based on Americans’ shifting patterns of spending on basic needs, and it varies the poverty line based on local housing costs and the family’s type of housing (such as renters versus owners with a mortgage). Unmarried partners are counted in the same SPM family, unlike in the official poverty measure and most previous implementations of the NAS measure. Long-Term Poverty Trends Since non-cash and tax-based benefits constitute a much larger part of government assistance than 50 years ago, the official poverty measure’s exclusion of these benefits masks progress in reducing poverty. Trying to compare poverty in the 1960s to poverty today using the official measure yields misleading results; it implies that programs like SNAP, the EITC, and rental vouchers — all of which were either small in the 1960s or didn’t yet exist — have no effect in reducing poverty, which clearly is not the case. While the federal government has only calculated the SPM back to 2009, Columbia University researchers have estimated the SPM back to 1967.[45] Using Census Bureau SPM data starting in 2009 and Columbia SPM data for earlier years, we find that government economic security programs are responsible for a decline in the poverty rate from 26.0 percent in 1967 to 14.4 percent in 2017, based on an “anchored” version of the SPM that uses a poverty line tied to what American families spent on basic necessities in 2018 adjusted back for inflation.[46] (See Figure 7.) Without government assistance, poverty would have been about the same in 2017 as in 1967 under this measure, which indicates the strong and growing role of anti-poverty policies.

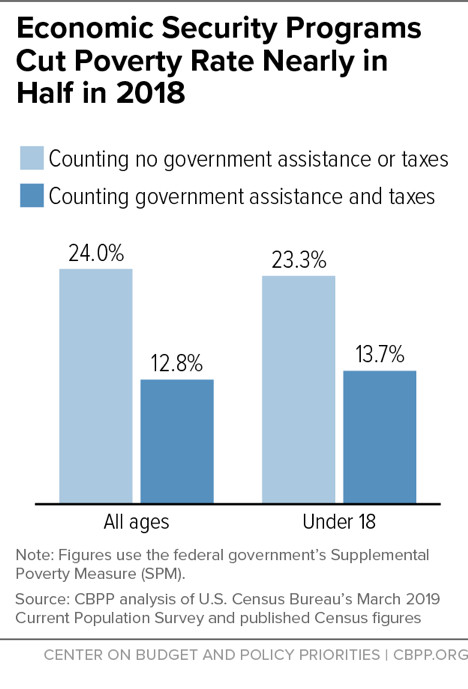

FIGURE 7: Poverty Rate Has Fallen Significantly Since 1960s Under Anchored Supplemental Poverty Measure In 2018 poverty fell again, to a record low of 12.8 percent. Data for 2018 are not strictly comparable to those for 1967 due to changes in the Census Bureau’s survey methods,[47] but the Census Bureau provides enough data about this survey transition to make clear that the SPM poverty rate reached a record low in 2018 when using the 2018 SPM poverty line adjusted back for inflation.[48] Similarly, child poverty reached a record-low 13.7 percent in 2018. Child poverty fell by nearly half over the last 50 years, according to data comparable back to 1967. This improvement is largely due to the growing effectiveness of government assistance policies. Nearly 8 million more children would have been poor in 2018 if the anti-poverty effectiveness of economic security programs (i.e., the safety net of government assistance policies) had remained at its 1967 level.[49] These findings underscore the importance of using the SPM rather than the official poverty measure when evaluating long-term trends in poverty. Effectiveness of Economic Security Programs Against Poverty Economic security programs cut poverty nearly in half in 2018, reducing the poverty rate from 24.0 percent to 12.8 percent and lifting 37 million people, including 7 million children, above the poverty line, according to CBPP’s analysis of SPM data.[50] (See Figure 8.) Further evidence of the effectiveness of these programs is the fact that poverty rose much less in the Great Recession when measured by the SPM rather than the official rate. Between 2007 (the year before the recession) and 2010 (the year after the recession), the anchored SPM rose by 0.7 percentage points, compared to 2.6 percentage points under the official poverty measure. The smaller increase under the SPM largely reflects the wider range of economic security programs included in the SPM and their success in keeping more Americans from falling into poverty during the recession, including the effects of temporary expansions in some economic security programs enacted as part of the 2009 Recovery Act. Deep Poverty

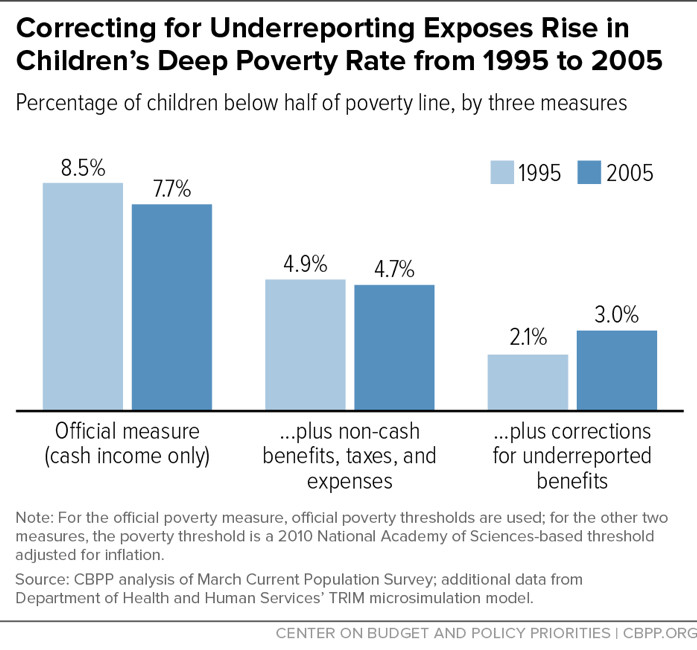

FIGURE 8: Economic Security Programs Cut Poverty Rate Nearly in Half in 2018 Measuring “deep” poverty, often defined as income below half of the poverty line, poses particular challenges due to underreporting of certain benefits, reflecting respondents’ forgetfulness, embarrassment about receiving benefits, or other reasons. Census’s counts of program participants typically fall well short of the totals shown in actual administrative records. Such underreporting is common in household surveys and can affect estimates of poverty and, in particular, deep poverty because people who underreport their benefits naturally make up a larger share of those with the lowest reported incomes. (While respondents may also underreport earned income, the net rate of underreporting in the CPS is thought to be much lower for earnings than for benefits.) In an analysis that corrects for underreporting of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), SNAP, and Supplemental Security Income benefits and uses a comprehensive NAS-based poverty measure similar to the SPM, CBPP analysts find that starting in the mid-1990s — when policymakers made major changes in the public assistance system — the share of children living in poverty fell but the share living in deep poverty rose,[51] from 2.1 percent in 1995 to 3.0 percent in 2005.[52] Notably, uncorrected CPS figures — whether using the official poverty definition or CBPP’s broader NAS measure — do not show this rise in deep child poverty. By the official measure, the share of children below half the poverty line fell from 1995 to 2005, from 8.5 percent to 7.7 percent. When counting non-cash benefits and taxes but not correcting for underreporting, the figures are essentially flat, at 4.9 percent in 1995 and 4.7 percent in 2005. Only the corrected figures show the increase. (See Figure 9.) FIGURE 9: Correcting for Underreporting Exposes Rise in Children's Deep Poverty Rate from 1995 to 2005 The increase in deep poverty for children was largely due to means-tested cash assistance benefits becoming less effective at shielding children from deep poverty. Over the 1995-2005 period, TANF cash assistance programs served a shrinking share of very poor families with children.[53]

FIGURE 10: Drop in Children's Deep Poverty Shows Strong Safety Net Response to Great Recession From 2005 to 2010, by contrast, the children’s deep poverty rate fell from 3.0 percent to 2.6 percent after correcting for underreporting.[54] (See Figure 10.) The decline, occurring despite the Great Recession, shows the striking effectiveness of economic security programs during this period, when policymakers supplemented programs’ built-in responsiveness through recovery policies such as expansions in tax credits and temporary measures such as an increase in SNAP benefit levels and enactment of the Making Work Pay tax credit.[55] Appendix ... Changes in CBO’s Methodology CBO’s methodology for analyzing the distribution of household income and taxes changed little between 2001 and 2012. CBO’s primary measure to rank households and calculate average federal tax rates was a broad measure of “before-tax income” that included both “market income”[56] and a broad set of government transfers. The latter included both social insurance benefits (Social Security, Medicare, unemployment insurance, and workers’ compensation) and means-tested transfers, both cash and in-kind, such as Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program benefits, SNAP benefits, and TANF cash assistance.[57] “After-tax income” equaled this “before-tax income” minus federal individual and corporate income, payroll (social insurance), and excise taxes. In its 2012 distributional analysis covering the years 1979-2009, CBO made two significant changes to its methodology for computing income, one concerning who bears the burden of corporate income taxation and the other concerning how CBO values government-provided health insurance such as Medicare and Medicaid.[58] CBO also made the consequential decision to switch from a version of the consumer price index (CPI) to the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price index in calculating real income (i.e., income after adjusting for inflation). The PCE index generally shows lower inflation than the CPI and hence faster real income growth. In previous reports, CBO had assumed that that the entire burden of corporate income taxes fell on owners of capital, so it subtracted 100 percent of corporate tax payments from the income of owners of capital in calculating after-tax income. Based on a review and analysis of the economic literature, CBO changed to allocating 25 percent of the corporate tax burden to workers and the remaining 75 percent to owners of capital. CBO’s previous method for measuring the value of government-provided health insurance aimed to measure the extent to which this coverage frees up income that a household can then use to meet basic food or housing expenses. That method capped the value of government-provided health insurance that is counted as income at the smaller of the actual cost to the government of providing the insurance and the maximum amount the household could afford to pay for health insurance without compromising its ability to meet other basic needs. The revised method that CBO put in place in 2012 uses the government’s average cost of providing health insurance to the household (as CBO has long done in valuing employer-provided health insurance benefits). For many low-income households, however, this approach produces a significantly higher measured income, while leaving the amount of cash income actually available to meet other basic needs unchanged.[59] In 2018, CBO made another substantial change, switching to use of “income before transfers and taxes” to rank households and calculate effective tax rates. Broadly speaking, this new measure consists of market income plus social insurance benefits, such as Social Security and Medicare. More specifically, it includes all cash income (including non-taxable income not reported on tax returns, such as child support), taxes paid by businesses,[60] employees’ contributions to 401(k) retirement plans, and the estimated value of in-kind income such as Medicare and employer-paid health insurance premiums. One effect of this change appears to be to shift more seniors with substantial Medicaid benefits — which, as a means tested entitlement, aren’t counted as income under this measure — into the bottom fifth of the income distribution.[61] As part of this 2018 revision, CBO also created its second new measure, “income after transfers and taxes.” It consists of the former “after-tax income” plus means-tested transfers, such as Medicaid and SNAP.[62] CBO states that the former method of using after-tax income for ranking was appropriate for analyzing the effects of federal taxes, but with the growing importance of means-tested transfers, the change allows the agency to analyze both means-tested transfers and taxes on the same basis. Together with the 2012 change in the treatment of government-provided health insurance, however, this change appears to strongly affect income trends for the poorest households, substantially raising the level and rate of growth of their measured income. End Notes

REPORT Economic Security Programs Cut Poverty Nearly in Half Over Last 50 Years NOVEMBER 26, 2019 CHART BOOK Chart Book: Economic Security and Health Insurance Programs Reduce Poverty and Provide Access to Needed Care DECEMBER 11, 2019 REPORT Child Poverty Falls to Record Low, Comprehensive Measure Shows Stronger Government Policies Account for Long-Term Improvement OCTOBER 5, 2017 More from the Authors Chad Stone Areas of Expertise ... Federal BudgetEconomyClimate ChangeImmigration Recent Work:

Danilo Trisi Areas of Expertise ... Poverty and InequalityImmigration Recent Work:

Arloc Sherman Areas of Expertise ... Poverty and InequalityFamily Income Support Recent Work:

Jennifer Beltran Recent Work:

1275 First Street NE, Suite 1200 Washington, DC 20002 center@cbpp.org ... 202.408.1080 ©2022 Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. All rights reserved.

| The text being discussed is available at | and |