Date: 2024-04-28 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00020421

PRODUCT: BATTERY

THE AMAZONBASICS BATTERY

Unraveling the Secret Origins of an AmazonBasics Battery ... One of Amazon’s smallest and most popular products has a surprisingly large footprint

THE AMAZONBASICS BATTERY

Unraveling the Secret Origins of an AmazonBasics Battery ... One of Amazon’s smallest and most popular products has a surprisingly large footprint

Illustration: Kelsey Niziolek

Original article: https://onezero.medium.com/unraveling-the-secret-supply-chain-behind-an-amazonbasics-battery-e7b9ead4d72e

Peter Burgess COMMENTARY

Some of the 'facts' about this little battery are upsetting, as it seems to be far more damaging to the environment than one might ever have imagined.

In the ealry 1970s I workd for a company, Gulton Industries, that had been a technological power in the 1960s. At the time it was a factor in the battery industry producing alkaline batteries for aircraft and the space program. They also built a prototype electric car in around 1968!

Battery technology has improved substantially since I was involved with batteries at Gulton, but I am aware that it is likely that the technology will not be powerful enough to solve the problem of energy storage at scale. I am more hopeful that climate friendly energy storage might come with the development of a 'hydrogen' economy which I think has better characteristics for a fast moving mobile economy than anything else.

This article highlights another issue ... and that is the deep problem of transparency and any associated accountability. For many years, I worked inside several corporate organization as a senior executive with the power ... and as a CFO the resonsibility ... to look at everything. My education and training had been broad ... not simply financial accountancy ... but had embraced the interaction of all sorts of disciplines in a complex way in the real world. This background was invaluable as I worked to get the most of good impact from always limited resources.

But what has become abundantly clear is that the outside world has very little understanding of 'what is going on under the hood' and almost any business organization, and especially the big multi-product, multi-location, mulkti-national companies that now dominate the economic landscape.

Ralph Nader made noise several decades ago to improve available information about products and made a difference, but I don't get the impression that this area of knowledge has been modernised very much in recent years (or even decades). As an older person, I know find I cannot read the tiny print on product labels and while social media has what might be described as a continuous immediacy, the information about a product contained on a label seems 'Oh so yesterday'!

It has been recognised for a long time that what people consume has a big impact of health and quality of life ... but information to help consumers make better decisions is at best archaic and mostly non existent. An 'app' that does this analysis in real time and continuously and completely should be in play. It is likely that something along these lines has already been developed, but has not been adopted by any of the big retailers ... rather when they adopt some new technology it is more likely to be to help drive customers in the direction of high margin products which are good for business profit and without paying much attention if any to the value proposition of the customer.

I have also been arguing for some considerable time that products should be better understood by the consuming public, and that includes understanding the pattern of cost, price and value througout the supply chain, during the period of use and then for the post use disposal chain.

The following article does this for a popular product being manufactured internationally and sold by Amazon. The information is very thought provoking but is a 'one off' piece of information and not at all clear what a next step should be. Are other brands of the product different and if so are they better or not!

And it should be a matter of great concern that 'tracking' is blanked out in a systematic way by those involved in logistics. Why is this happening ,,, and how common is it? This article raises a whole lot of transparency and accountability questions that don't seem to have a good easy answer.

Peter Burgess

One of Amazon’s smallest and most popular products has a surprisingly large footprint

Written by Sarah Emerson ... Staff writer at OneZero covering social platforms, internet communities, and the spread of misinformation online.

October 30th, 2019·(Accessed April 2021)

I heard the “pop!” from my living room as a brand-new pack of Amazon batteries spontaneously exploded on the kitchen counter, oozing a gritty black substance in fits and spurts. The small, unassuming item is one of Amazon’s most popular “in-house” products sold under the AmazonBasics label. With nearly 20,000 customer reviews, its popularity dwarfs that of most other AmazonBasics items, which include electronics, homewares, and random odds and ends.

The batteries are also highly rated — had I received a defective set? I scoured the comments page for the alkaline battery for reviews containing the word “explode,” revealing dozens of experiences like mine. One person said the batteries had burst in their wife’s breast pump. Others had toys and appliances ruined by leaky fluid. Some customers blamed this on alleged Chinese manufacturing, but Amazon vaguely claims in the product’s description that they are “made in Indonesia using Japanese technology.”

Over the past month, I have tried to uncover the hidden life cycle of this simple AmazonBasics battery. Amazon is fiercely secretive about its corporate footprint and masks its operations through a discreet network of outsourcing, making its supply chain hard to unravel. Its AA battery is no different. The product is indeed made in Indonesia, but not by Amazon, I learned. The company buys the batteries from a supplier and reskins them as its own, much like Trader Joe’s and its eponymous food brand. Amazon has never voluntarily divulged the sources of AmazonBasics items, but it confirmed OneZero’s reporting on where its AA batteries come from.

Faster, cheaper delivery always comes at a cost — to humans and the environment.Though I discovered where the batteries were made, I was unable to locate the source of their materials, for example. The difficulty in understanding the supply chain of even a simple component shows how Amazon’s operations are deliberately designed to be a black box. This secrecy allows the commercial titan to be ruthlessly competitive, delivering cheaper items faster than rival stores. But it also makes it harder for consumers who wonder whether their purchases are ethically or sustainably sourced to even begin finding answers. Beyond obscuring why merchandise might be defective — or explosive, in my case — it hinders those of us who just want to know: Where does it all begin?

TThere’s a plain white building in West Java, Indonesia, where workers meticulously assemble batteries for Fujitsu, a Tokyo-based technology company and covert supplier for AmazonBasics. Unlike Amazon’s distribution centers, which are emblazoned with its black-and-orange logo, nothing outwardly betrays that a popular AmazonBasics item is made here.

Technically, Fujitsu’s subsidiary FDK runs the alkaline factory. You’ll find it in the West Javanese city of Bekasi, one of Indonesia’s liveliest industrial centers. I decided to call the subsidiary after stumbling across a review for the AmazonBasics batteries that mentioned, without elaborating, that they appeared to be “manufactured by Fujitsu.”

An FDK employee confirmed to OneZero that AmazonBasics is an authorized distributor of its batteries and per their agreement is required to buy at least $100,000 of its product annually. Amazon later confirmed to OneZero that FDK is one of the companies that works with AmazonBasics.

The Fujitsu building in West Java, Indonesia. Photo: Google Maps

Fujitsu is one of the world’s oldest information technology companies, founded in 1935 in prewar Japan, with its roots in one of the country’s industrial zaibatsu, or family-owned business monopolies. The company went on to create Japan’s first homegrown computer and today boasts a global retail empire of hardware, software, and personal gadgets. In 1989, FDK expanded into Indonesia as FDK-Intercallin, eventually opening a production plant there — becoming the sole maker of Fujitsu alkaline batteries outside of Japan.

According to historians, Japan is revered for perfecting the modern battery’s secret sauce: a finicky black powder called electrolytic manganese dioxide that helps to cycle energy through the device.

“The Japanese were early in figuring out how to manufacture electrolytic manganese dioxide,” said Jay Turner, a professor of environmental studies at Wellesley College. The product had always required pristine manganese dioxide, a compound that was difficult to mine without impurities. “But around World War II, they figured out how to manufacture a pure form of it that’s better than the natural stuff.”

All the experts OneZero spoke to said that Indonesia, a nation of 264 million people, is not a huge player in the battery industry, which has long been dominated by countries like China, Japan, and Korea. Amazon’s investment in a Southeast Asian market, therefore, is peculiar.

“If anything, Amazon should have greater control over its AmazonBasics supply chain… The fact that they haven’t been doing this for so long is kind of suspicious.”FDK declined to comment on the conditions of its Indonesian factory. Lax environmental standards may be one explanation for the factory’s location. Other factories in Bekasi are responsible for carcinogenic air pollutants and putrid river waste. Fujitsu’s sustainability report shows that its Indonesian operations are among the dirtiest, ranking the highest on waste production. In 2016, its Bekasi site produced 100 tons of waste more than the next worst producer, FDK Energy.

“On the Indonesian regulation front, I would say if anything it’s limited or not well-enforced, so the risks are low [for a company like Fujitsu],” said Alexis Bateman, director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Sustainable Supply Chains project, which aims to empower businesses to adopt sustainable development strategies through research. Indonesia has another quality that’s a boon to battery makers: its deposits of precious natural resources.

Fujitsu declined to comment on the source of its battery materials and whether it’s tapping into Indonesia’s rich manganese supply. There is zero publicly available data on where the company gets its materials, save for an agreement that says it will not buy conflict minerals (tantalum, tin, gold, tungsten, and cobalt) from suppliers that fund human rights abuses. But battery analysts say that companies such as Tesla and Apple, which require batteries of a very different kind, may be looking to Indonesia as resource stockpiles begin to peter out. Tesla is notably in talks to build a battery factory in Central Sulawesi; meanwhile, the Indonesian government is enforcing an export ban on nickel and copper, possibly to bolster its own battery operations.

Thanks to a product sheet, however, we know that Fujitsu’s battery is made using manganese dioxide, graphite, zinc, and potassium hydroxide. It also likely contains paper, nylon, PVC, and steel. It’s unclear what, if any, percentage of these materials are recycled or recyclable.

“The materials aren’t toxic, they don’t pose a significant threat to human health, and they’re not that heavily regulated,” Turner said. “The alkaline is basically refined dirt in a cylinder.”

But their production isn’t so benign. Manganese is linked to human rights abuses, occupational safety violations, and child labor, according to RCS Global, a social responsibility consulting firm. Seventy-six percent of manganese comes from South Africa, China, Australia, and Gabon, RCS Global notes, but there is “virtually no comprehensive traceability” along the supply chain. In other words, while there’s a significant chance that manganese may have been mined in abusive conditions, it’s difficult to pinpoint if a specific company is benefitting, because the mineral is filtered through a number of intermediaries. (The same is true of other minerals.)

Basically nothing is being done to address the risks of manganese production, says the Responsible Sourcing Network, a nonprofit that focuses on human rights abuses in labor. Zinc mining has also been found to release harmful emissions into the air, such as sulfur dioxide, which can be toxic to human health.

“At Amazon, we are strongly committed to ensuring that the products and services we provide are produced in a way that respects human rights and the environment and protects the fundamental dignity of workers,” an Amazon spokesperson told OneZero. “We engage with suppliers that are committed to these same principles, and we set exacting standards for suppliers of goods and services for Amazon and Amazon’s subsidiaries.”

TThe battery becomes less trackable the further it progresses down the chain. This is overwhelmingly due to U.S. shipping rules that allow companies to move product virtually in secret. And as Amazon expands into all modes of transport — cars, trucks, air and ocean freight — its logistics will likely become even more invisible.

“Amazon is big not because it’s offering new things, but because of its command of logistics,” said Jean-Paul Rodrigue, a professor at Hofstra University who studies transportation, logistics, and freight distribution. “Commercial shipments are subject to private contracts, and Amazon is under no obligation to reveal this information to anyone. Only a ship’s manifest would, for customs purposes,” he added.

In 2015, the Greek container ship COSCO Beijing left Jakarta, Indonesia, with 410 pallets of AmazonBasics alkaline batteries. The product filled four cargo containers and was dispatched by PT FDK Indonesia out of Bekasi, with Amazon Fulfillment Service listed as the consignee (or seller). The ship briefly stopped in Malaysia and Singapore before crossing the Pacific to the Port of Long Beach, California, and then on to Seattle, Washington, where its cargo was unloaded and taken to an unknown destination.

This is according to the shipment’s bill of lading, acquired by Panjiva, a supply chain research unit at S&P Global Market Intelligence that purchases commercial shipping data from the U.S. Customs and Border Protection to provide global import and export insights for its customers. The 2015 shipment was the only one that Panjiva could find, possibly because Amazon conceals most of its shipping documents, but one had fallen through the cracks.

The next leg of the battery’s journey, from its warehouse to your doorstep, is more speculative. On the particular box that I purchased, small letters say “imported by importer” in Spanish, above the address for Amazon’s facility in Mexico City. Below that, in German, an address for Amazon’s Luxembourg facility is also given.

Amazon operates 75 fulfillment centers and 25 sortation centers across North America — a footprint so large that there’s an Amazon warehouse within 20 miles of half the U.S. population, according to Curbed. Globally, Amazon has more than 175 operational fulfillment centers. The company also dispatches an estimated 48% of its own packages through its last-mile delivery service, Amazon Logistics. But unlike UPS or FedEx, which offer detailed tracking information, Amazon Logistics scrubs any data that precedes an item’s arrival at an Amazon site. For example, when I ordered a box of AmazonBasics batteries, my tracking number began with “TBA,” denoting that it was delivered via Amazon Logistics, and only went as far back as its departure from an Amazon warehouse in Newark, California. Amazon acknowledged but would not explain why tracking is assigned only after a product has left a fulfillment center.

Faster, cheaper delivery always comes at a cost—to humans and the environment. Amazon has been accused of underpaying, surveilling, and overworking the people that it contracts as drivers. In August, a BuzzFeed News report exposed the fatal conditions that Amazon creates for its next-day delivery drivers, resulting in consequences for which Amazon refuses to take responsibility. Its delivery emissions are also shocking; according to one estimate, Amazon shipments produced 19 million metric tons of carbon in 2017, or the equivalent of nearly five coal power plants. CConsumers are most intimate with the end of a battery’s life cycle — its use and eventual disposal. These are the phases that environmentalists are also most preoccupied with as electronic waste becomes a (literal) growing concern in our technological era.

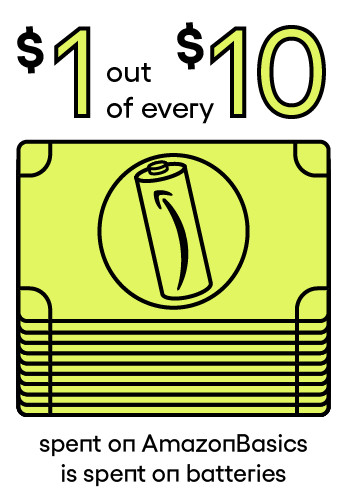

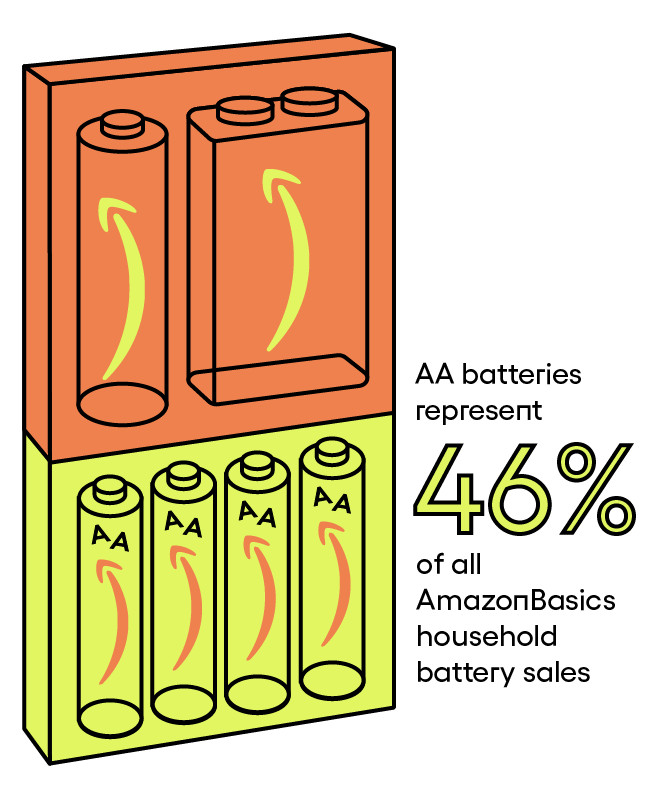

The AA battery accounts for nearly half of AmazonBasics’s battery sales, capturing 46% of those online purchases, according to data provided to OneZero by 1010data, a company that provides consumer transaction insights. One dollar out of $10 spent on AmazonBasics is spent on batteries, and the AA alkaline battery accounts for roughly 4% of the label’s overall sales. This has put AmazonBasics at the top of the online AA battery market, above familiar brands like Energizer and Panasonic.

“Amazon’s ability to aggressively market its in-house battery brand has helped it become the leader in online household battery sales, but national brands like Energizer and Duracell are competing aggressively to maintain their share,” said Matt Pace, senior director at 1010data.

Despite the battery’s widespread use, some experts say its environmental impacts are insidious and vastly underestimated. “The greatest burden lies far upstream of the manufacturing facility itself,” in the extraction of raw materials, researchers at MIT’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering wrote in a 2011 study on the life cycle of alkaline batteries.

“Of the phases… directly within control of the battery manufacturing industry, the manufacturing facility has the largest impact [through electricity use],” the study noted. U.S. battery production sources the bulk of its energy from fossil fuels, it adds, with renewables accounting for just a fraction of these power needs. Together, sourcing and processing add up to 88% of a single-use battery’s environmental impact.

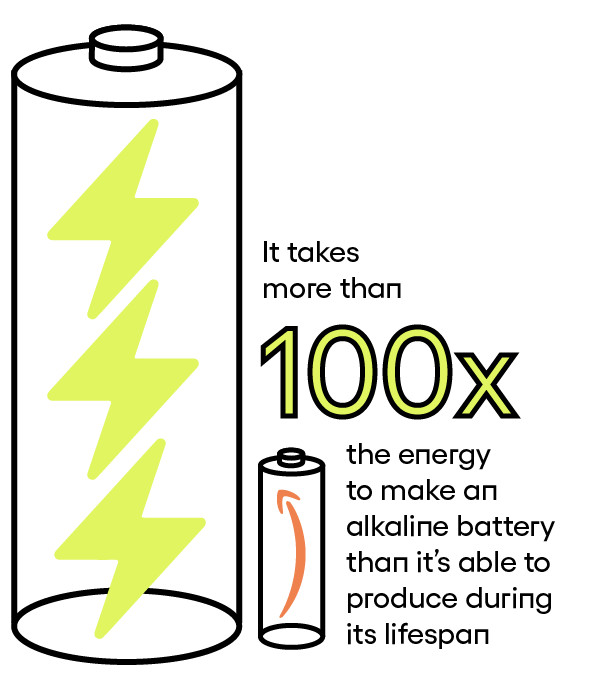

Using the MIT study’s data, Turner co-authored a 2015 paper published in the Journal of Industrial Ecology, estimating that “it takes more than 100 times the energy to manufacture an alkaline battery than is available during its use phase.” And when the entirety of a battery’s emissions are added up — including sourcing, production, and shipping — its greenhouse gas emissions are 30 times that of the average coal-fired power plant, per watt-hour.

All of which is to say: An appliance powered by an alkaline battery consumes more carbon than an appliance that’s plugged into an electrical outlet, according to the study.

Still, conversations about the environmental footprint of batteries largely revolve around end-of-life disposal, recycling, and “upcycling.” Most states allow people to throw their spent batteries in the trash in lieu of voluntary or mandatory collection programs. (California is the exception, considering all batteries to be hazardous waste, though the state offers only vague guidelines on what to do with them.) But while batteries are one of the largest sources of heavy metals in waste streams, there is no broad U.S. policy that classifies various battery types as toxic or nontoxic or that dictates their disposal. Regarding the alkaline battery, policymakers currently disagree on whether it’s harmful when landfilled, the MIT study notes.

“The problem is they’re really small and really distributed, so to collect and recycle them takes a lot of energy,” Turner said. “By the time you’ve done this, you’ve used more energy than you’ve saved in the process.”

Fujitsu says consumers can decrease waste by replacing portable batteries with its “long-lasting” alkaline or rechargeable batteries. Though Amazon claims to be working toward closing its own waste loop, it appears to be doing less than other prominent battery sellers to incentivize recycling. Only its rechargeable batteries contain recycling information, but Amazon says it may soon include this information for its disposable batteries as well.

The impact of an Amazon battery may seem inconsequential when compared to the company’s fossil fuel alliances, labor abuses, and billions of dollars in military contracts, but it matters at a time when Amazon claims to be doing better on climate change. In September, CEO Jeff Bezos announced an ambitious “Climate Pledge” after several thousand Amazon employees demanded the company adopt a climate action plan. The commitment is a big one, putting Amazon on a track to reach net zero emissions by 2040 and relying solely on renewable energy company-wide by 2030. But hidden in the pledge is the fact that Amazon has only just begun to track its carbon footprint, a whopping 44.4 million metric tons in 2018, nearly equivalent to the output of Switzerland or Denmark. The company says this equation includes production — and Amazon told OneZero that it calculates its footprint in accordance with industry standards, and that private-label items are accounted for — but its reporting is overly generalized, combining things as disparate as “business travel” and “Amazon-branded product manufacturing” together under “emissions from indirect sources.” By merging these emissions, Amazon is hiding what portion of that number originates downstream from outsourced manufacturing.

“If anything, Amazon should have greater control over its AmazonBasics supply chain,” Bateman said. “The fact that they haven’t been doing this for so long is kind of suspicious. It’s not like they’re a new company.”

I never discovered why my AmazonBasics batteries exploded. An Amazon spokesperson said the company had once investigated the problem, even bringing in a third-party testing lab to inspect the product’s design. “We thoroughly investigate any and all concerns of this nature to ensure the safety of our products,” the spokesperson told me. My unused pack now sits in a cupboard, collecting dust because I don’t know how to recycle it.

The complexity of Amazon’s battery is concealed by its everyday utility — ping-ponging across the globe in relative secret, which is how Amazon wants it to remain, and how it likely will. “Why should Amazon reveal its supply chains to its competitors?” Rodrigue asked. “Their supply chain is their advantage.”

Update: A previous version of this article misstated one unit used to measure emissions. It is a watt-hour. Also, a previous version included incorrect information about how Fujitsu’s Indonesian operations rank in terms of greenhouse gas emissions and water usage. They are near the middle, but rank highest in terms of waste production.

Sarah Emerson ...Staff writer at OneZero covering social platforms, internet communities, and the spread of misinformation online. Previously: VICE