Date: 2025-10-05 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00021308

FEDERAL RESERVE

INTEREST RATE POLICY

Paul Krugman, NYT Opinion ... How softies seized the Fed

TPB ... as effective as pushing on a piece of string

INTEREST RATE POLICY

Paul Krugman, NYT Opinion ... How softies seized the Fed

TPB ... as effective as pushing on a piece of string

Paul Krugman

Burgess COMMENTARY

I am usually quite positive about economic analysis from Paul Krugman ... but not so much this time. The main reason for my discomfort is that the outcome of monetary policy that emerges from the Fed and other Central Banks around the world depends a lot on the productivity of the technology that is being used within the economy. It seems to me that most academic economists give this a very low weight, if any weight at all.

Though I had academic training in economics (at Cambridge), I would argue that cost accounting in industrial organizations has a more critical role in inflation outsomes than monetary policy. Production costs determine how profitable a company and an economy is able to be. If production costs go down, a company can make more profit without raising prices ... and ceteris paribus, you don't get 'cost push' inflation.

When there is 'demand pull' and little or no cost-push within a company, company management is in a position to choose to what extent they will exploit the emerging profit growth opportunity for their own benefit or share the benefit with consumers. Most companies seem to choose to benefit those that get value from the companies' profit performance like managers with profit performance incentives and investors.

My analysis of the last 50 years suggests that the main reason that there has been rather little inflation since 1980 has been the ability of companies to tale advantage of low costs in global supply chains in ways that were not possible before. This was enabled in large part by digital technology and massive improvement in education around the world ... not to mention the quite simplistic but powerful role of money and profit as a business incentive.

None of this seems to appear in the analysis by Paul Krugman below.

Peter Burgess

How softies seized the Fed

Paul Krugman

By Paul Krugman ... NYT Opinion Columnist

November 23, 2021

Who should lead the Federal Reserve? President Biden faced a difficult choice. Should he reappoint Jay Powell, a monetary dove who believes that the current inflation spike is probably temporary but might revise his views in the light of evidence? Or should he nominate Lael Brainard, a monetary dove who believes that the current inflation spike is probably temporary but might revise her views in the light of evidence?

In the end, he went with the monetary dove.

OK, Powell and Brainard aren’t identical. Powell is or was a Republican, Brainard is a Democrat; Brainard took a harder line on financial regulation after the 2008 crisis, which is why progressives like Elizabeth Warren opposed Powell’s reappointment. But when it comes to the Fed’s core responsibility, setting monetary policy, there was never any doubt that the next chair would be someone reluctant to raise interest rates and eager to keep job growth high.

How did that happen? Traditionally, central bankers — people who run institutions like the Fed that control national money supplies — pride themselves on their sternness, their willingness to impose economic hardship. William McChesney Martin, who headed the Fed in the 1950s, famously described its job as being to take away the punch bowl just as the party really gets going — that is, to raise interest rates as soon as there was any indication of rising inflation.

But the Fed is a technocratic institution that takes ideas and analysis seriously, that is willing to revise its views in the light of evidence. On the eve of the 2008 crisis it believed, with considerable justification, that giving low inflation priority over other considerations was in fact the right policy. Since then, however, there has been accumulating evidence that targeting inflation isn’t enough — indeed, that the Fed has consistently been taking away the punch bowl too soon.

Milton Firedman

The story here begins with a famous 1968 speech by Milton Friedman (and an independent analysis by Edmund Phelps that reached similar conclusions). Friedman argued, contrary to what many economists believed at the time, that monetary policy couldn’t be used to target low unemployment on a sustained basis. Any attempt to keep unemployment below its “natural rate” — usually referred to these days as the NAIRU, the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment, to avoid the implication that unemployment is somehow good — would, he asserted, lead to ever-accelerating inflation, and it would take a period of high unemployment to get inflation back down.

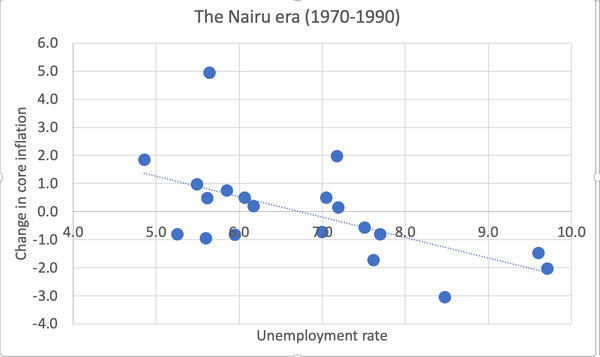

The experience of the 1970s and ’80s seemed to confirm this analysis. Here’s the unemployment rate versus the change in the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation from 1970 to 1990. Low unemployment seemed to be associated with ever-rising inflation, and getting inflation back down did indeed seem to require high unemployment:

Milton Friedman was right ...FRED

If you accepted this “accelerationist” hypothesis, the Fed’s job wasn’t to keep unemployment low, because it couldn’t do that. It was, instead, merely to provide stability in both prices and employment.

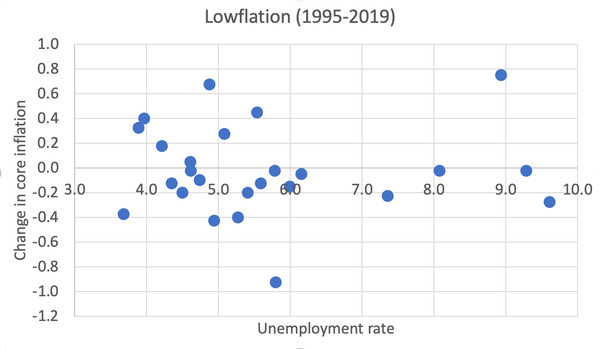

But here’s the thing: Since at least the mid-1990s, the data haven’t looked anything like that. Do the same plot from 1995 to the eve of the pandemic and there’s no evidence for the accelerationist hypothesis:

... or maybe not.FRED

Notably, unemployment dipped below 4 percent both at the end of the 1990s and at the end of the 2010s, in each case without provoking accelerating inflation, while even very high unemployment after 2008 failed to produce the deflationary spiral that Friedman-type analysis would have predicted.

And if low unemployment doesn’t lead to accelerating inflation, it seems all too likely that we have consistently been running the economy too cold, sacrificing jobs and output unnecessarily. While the Fed hasn’t explicitly admitted this, it’s clearly a regret that weighs on its policy now.

There’s also another consideration that has made the Fed more dovish: fear that the effects of tight money may prove very hard to reverse.

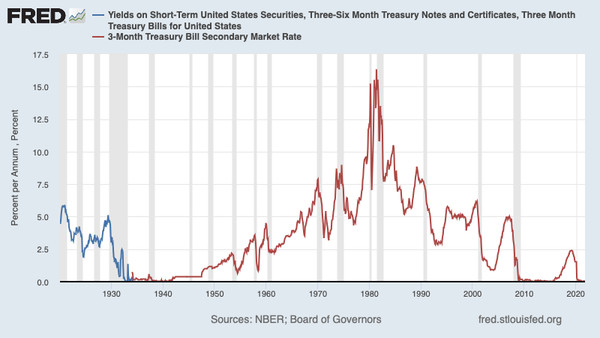

Back in 1935, Mariner Eccles, another Fed chairman, argued that the Fed could do little to reverse deflation because you can’t push on a string. This made sense at the time: The Fed had very little ability to cut interest rates, because they were already near zero. But for a long time economists assumed that those Depression-era conditions would never come back, that the Fed could always engineer an economic recovery when it wanted to.

As it turns out, however, interest rates can indeed hit the “zero lower bound” in the 21st century; in fact, that has been the norm since 2007:

Zero is back.FRED

This in turn means that while everyone is talking about inflation risks right now, the Fed is also concerned about the risks of overreacting to inflation. If it raises interest rates and that pushes the economy into a recession, it might not be able to cut rates enough to get us out again.

So if you ask why monetary doves rule the Fed roost, it’s not just a matter of personalities — or ideology. The past couple of decades have highlighted the downsides of hawkishness, and the Fed doesn’t want to repeat what it now, quietly, views as past mistakes.

I will be taking a break for the rest of the week for Thanksgiving. See you back here next week.

---------------------------------------

The New York Times Company. 620 Eighth Avenue New York, NY 10018