Date: 2026-01-17 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00017447

Middle East Leadership

Mohammed bin Salman (MBS)

Mohammed bin Salman ... How Saudi Arabia's crown prince rose to power

Peter Burgess

Mohammed Bin Salman over a filtered photo of Riyadh

Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, known as MBS, is transforming and modernising a deeply conservative country.

Yet at the same time, he has dragged Saudi Arabia into a war in Yemen, and locked up women’s rights protesters, Islamic clerics and bloggers. He is also widely suspected of being behind the murder of critic Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul a year ago.

So just who is the man they call MBS?

The note-taker

Jeddah, September 2013, and under a blazing Red Sea sun the palace guards stepped aside as our car swept through the reinforced gates. It had taken days to get an audience with the ageing then-Saudi Crown Prince and Defence Minister Salman bin Abdulaziz.

Years earlier, in 2004, Prince Salman had been governor of Riyadh when gunmen ambushed our BBC team, shooting me six times, leaving me for dead and killing my Irish cameraman, Simon Cumbers. I’m told the prince visited me in hospital but I have no recollection since I was in a medically induced coma.

Today Salman is king and in frail health. Even then, in 2013, I noticed he was resting his hand on a walking stick as we sat on ornate gilt chairs in a palace reception room.

His long, solemn face cracked frequently into a smile as he spoke slowly, in English, in a deep, stentorian voice, telling me how much he liked London.

Riyadh, the capital of Saudi Arabia

He had seen extraordinary changes. As governor of the Saudi capital Riyadh for five decades, he had watched it morph from a dusty desert town of 200,000 into a teeming metropolis of over five million people.

Throughout this royal meeting I was only vaguely aware of someone sitting behind me at the back of the room, quietly taking notes.

I assumed, wrongly, that he must have been some sort of chef de cabinet, a private secretary to the crown prince. I could see he was tall and heavily built, with neatly trimmed stubble. He was wearing the traditional bisht - the cloak hemmed with gold embroidery that denotes rank and standing.

The audience over, I introduced myself to this silent note-taker. We shook hands and I asked him who he was.

“I am Prince Mohammed bin Salman,” he replied, adding modestly, “I am a lawyer. You have been speaking to my father.”

I had absolutely no idea, on that baking hot afternoon in Jeddah, that this quietly spoken and still relatively unknown 28-year-old was set to become one of the most powerful and yet most controversial leaders the Arab world had ever seen.

Khashoggi

The last known sighting of Jamal Khashoggi, entering the Saudi consulate in Istanbul

On 2 October at 13:14, Jamal Khashoggi walked into a nondescript beige building in the Levent area of Istanbul.

A prominent writer and outspoken critic of MBS, he was only visiting the Saudi consulate to get some divorce papers certified.

But once inside he was overpowered by a hit team of security and intelligence agents sent from Riyadh, murdered, dismembered and his body disposed of, never to be found.

Thousands have died in the war that has devastated Yemen, many through Saudi-led airstrikes. Hundreds of Saudis critical of MBS’s policies have vanished into prisons. And yet it took this particularly gruesome murder of a journalist to turn much of the world against the Saudi crown prince.

Despite official Saudi denials, Western intelligence agencies believe that at the very least it was highly likely MBS knew in advance about the operation to silence Khashoggi. According to reports, the CIA believes he actually ordered it.

In an interview aired on 29 September with CBS 60 Minutes, the crown prince went so far as to “take full responsibility” for what happened. In an earlier PBS interview he said it happened “under his watch”. Yet this is not the same as accepting culpability, which he and his government still deny.

A key link in this whole, hideous murder mystery is one of MBS’s closest former advisers, a 41-year-old ex-air force man, Saud al-Qahtani.

Until he was dismissed from his job soon after the Khashoggi murder- on the orders of King Salman - he was the crown prince’s unofficial gatekeeper in the all-powerful royal court.

Jamal Khashoggi

One of the few pictures of Saud al-Qahtani - his Twitter profile image

Al-Qahtani is said to have managed an aggressive cyber surveillance strategy that monitored Saudis both at home and abroad, using intrusive software programmes. According to some reports, this included turning their mobile phones into bugging devices without the owner knowing.

Anyone critical of MBS or his policies found themselves trolled with abusive and threatening messages on social media. With over a million Twitter followers, al-Qahtani was able to mobilise an “army of flies” to harass and shame perceived enemies.

By the summer of 2017, with Saudi bloggers, democracy campaigners, human rights activists and others getting rounded up and imprisoned. Jamal Khashoggi knew he, too, was in danger.

In June that year, the same month that MBS became crown prince, Khashoggi got out of Saudi Arabia while he could, flying into exile in the US.

The 59-year-old journalist had always called himself a Saudi patriot - he used to be the media adviser to the Saudi ambassador to London in the early 2000s, and I would go and have coffee with him in those days.

But after moving to the US he wrote Washington Post columns that grew increasingly critical of MBS’s autocratic style. The crown prince is said to have become irritated.

The journalist started to receive calls from Riyadh urging him to return, promising him safe passage and even a job in government.

Khashoggi didn’t trust these assurances. He told friends that al-Qahtani’s team had hacked into his emails and text messages and read conversations with other dissenting figures.

Khashoggi and others had a plan to launch a movement for free speech in the Arab world. He had 1.6 million Twitter followers and was one of the Middle East’s most prominent journalists.

To MBS and his close advisers, Khashoggi would have been seen as a clear and present threat, although again, the crown prince denied this in his CBS interview.

Historically, there have been several cases of the Saudi leadership abducting a number of “wayward” citizens, even princes, and taking them back to Riyadh to “bring them back into line”, as commentators have put it. But not murder. An assassination in a foreign city would have been a drastic departure from their normal modus operandi.

Khashoggi’s death quickly became an international scandal.

After an initial, bungled explanation of what might have happened to Khashoggi in Istanbul, the Saudi authorities have gone to great lengths to distance MBS from the scandal.

It was a rogue operation, they said, a case of people grossly exceeding their orders or taking matters into their own hands. But the CIA, and other Western spy agencies, have listened to the gruesome audio tapes that Turkey’s MIT intelligence agency secretly recorded from inside the Saudi Consulate.

For more on this story, watch Panorama: The Khashoggi Murder Tapes on BBC iPlayer and read Jane Corbin's report, The secret tapes of Jamal Khashoggi's murder

And when the US launched sanctions against 17 individuals it suspected of being involved in the murder, Saud al-Qahtani was top of the list.

To date, there is still no “smoking gun” that unequivocally ties MBS to the murder.

But a classified CIA assessment obtained by the Wall Street Journal showed at least 11 text messages sent by MBS to al-Qahtani before, during and after Khashoggi was murdered.

And let’s be clear here. In the Gulf Arab states, where I have lived and worked for years, there is no such thing as “a rogue operation”. They simply do not happen. Nothing, but nothing, gets done in the Gulf without sign-off from above.

A Turkish policeman stands outside the door of the Saudi consulate in Istanbul

Khashoggi's murder sparked protests across the world

In August 2018 last year, before the murder, Saud al-Qahtani put out a telling tweet. It ran: “Do you think I make decisions without guidance? I am an employee and an executor of the orders of the King and the Crown Prince.”

No-one has suggested King Salman himself had anything to do with the murder. But the plot does appear to have been hatched from right within his favourite son’s inner circle. “It is inconceivable,” said one former British intelligence officer, “that MBS did not know about it.”

“The Khashoggi murder was a stain on our country, our government and our people” ... Prince Khalid bin Bandar al-Saud, Saudi ambassador to LondonSo where is al-Qahtani and why isn’t he on trial?

I put this question recently to the newly appointed Saudi Ambassador to London, Prince Khalid bin Bandar al-Saud. The ambassador assured me that al-Qahtani had been removed from his post and was being investigated. If he is found to be involved he will be prosecuted, he told me. But reports from Riyadh show that although he is keeping a low profile, al-Qahtani has not been detained.

“He is not showing up at court but he’s still involved in cyber-security issues and other projects,” says one Gulf resident with close knowledge of MBS’s circle. “He’s lying low but they are tapping into his expertise.”

The commentator went further, adding that to the people around MBS, al-Qahtani is someone who “took one for the team”. “Yes, the operation [in Istanbul] went wrong but he executed his orders.”

The Saudis have put 11 men on trial over the Khashoggi case. Proceedings began in January and nine months later there is still no word of any convictions or punishments or even an indication of when the trial might conclude.

The Saudi justice system is notoriously opaque at the best of times, with judgements often left to the whim of a judge rather than following any prescribed penal code.

One senior figure who has been named by the authorities is Maj-Gen Ahmed al-Assiri, the deputy head of intelligence and previously the spokesman for the controversial Saudi-led air campaign in the Yemen war.

Having met him in Riyadh on several occasions, al-Assiri did not strike me as the sort of person to come up with a plan without first getting clearance from above.

Whatever the eventual outcome of the shadowy trial one thing is clear - the Khashoggi murder has done enormous and lasting damage to both MBS’s and Saudi Arabia’s global reputation.

“Let me be clear,” the Saudi ambassador to London told me in September, with surprising frankness for such a senior member of the ruling family. “The Khashoggi murder was a stain on our country, our government and our people. I wish it hadn’t happened.”

A softer Saudi?

A woman drives her car in Riyadh just after midnight, 24 June 2018, when the law allowing women to drive took effect

Night time in mid-December in the suburb of Diriyah, just outside the capital, Riyadh. A huge, mixed crowd of young Saudis in Western dress is moving in time to the music, smartphones raised above their shoulders, lasers and lights criss-crossing the auditorium.

David Guetta, the French house DJ, is on the decks. At the same venue, women exercise their newfound freedom to drive by arriving in their own top-of-the-range sports cars to watch Riyadh’s inaugural Formula E race. There are concerts by the Black Eyed Peas and Enrique Iglesias.

This is the new Saudi Arabia as decreed by its modernising crown prince. Entertainment is in, cultural austerity is out.

For anyone who has lived in or visited Saudi Arabia over the past 40 years, this transformation is quite extraordinary.

Car and bike rally in Jeddah

Such a free mingling of the sexes in a party atmosphere would have been totally unthinkable only a short while ago, forbidden by the conservative religious clerics on whose support the ruling family has relied for its legitimacy.

The Saudi Arabia I have always known has had an ascetic, joyless public face, a place where the Mutawwa, the religious police, closed down popular shisha cafes in Riyadh and ordered shops not to play music as part of their own strict interpretation of Sharia [Islamic law].

Since becoming crown prince in 2017, MBS has set out - with the king’s backing - to reverse this image of Saudi Arabia being a fun-free zone. Cinemas, women driving, public entertainment - all were banned for years. Now, he has said, he wants to make his country a softer, kinder place.

The Kingdom's ban on cinemas was only lifted in 2018

‘What happened in the last 30 years is not Saudi Arabia,” MBS pronounced in October 2017. “After the Iranian revolution in 1979 people wanted to copy this model in different countries, one of them is Saudi Arabia. We didn’t know how to deal with it. And the problem spread all over the world. Now is the time to get rid of it.”

In fact, Saudi Arabia, a profoundly tribal and conservative country, has never enjoyed the sort of charms and distractions of urban Arab melting pots like say, Cairo or Baghdad. Nevertheless, MBS’s words were exactly what the White House wanted to hear.

By then, close ties had already been forged between Washington and the new crown prince. Donald Trump chose Riyadh for his first overseas presidential visit in May 2017, and his son-in-law Jared Kushner formed a close working relationship with MBS.

March 2018: MBS with Donald Trump in the White House

Pursuing a “moderate Islam”, MBS has issued permits for public concerts and even a Coptic Christian mass.

At home, his popularity has soared, especially among the predominantly young population who are tired of being ruled by men more than half a century older than them. MBS is just 34 - the first national leader young Saudis can relate to.

“He loves fast food, like hot dogs, and he drinks a lot of Diet Coke,” says one Gulf businessman, who does not want to be named. MBS is said to have grown up playing Call of Duty and to be a huge admirer of tech.

At an investment forum in Riyadh in November 2018 young Saudi women were rushing up and asking to take selfies with the crown prince. He was only too happy to oblige, his stern, inscrutable features breaking into a film star grin.

“He’s been a long-awaited leader in Saudi Arabia,” says Malek Dahlan, an international lawyer. “Saudi hasn’t seen someone of his charisma since his grandfather, King Abdulaziz.”

Participants take photos next to a picture of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman during the Misk Global Forum in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, November 14, 2018

“My impression,” says Sir William Patey, who was Britain’s ambassador to Riyadh from 2006-2010, “is that most Saudis, particularly the young, support the crown prince and the direction of travel.” In reference to MBS’s extraordinary concentration of power into his own hands, he adds: “They have traditionally seen authority more dispersed but understand that big change requires more decisive decision making.”

Another former British diplomat who has met MBS on numerous occasions but, like many, prefers not to be named, says:

“MBS has this extraordinary self-belief. He’s like a solar flare. He just explodes into ideas and energy. He can be over-confident and there is a streak of amateurism there.”But there is also a streak of something altogether more sinister.

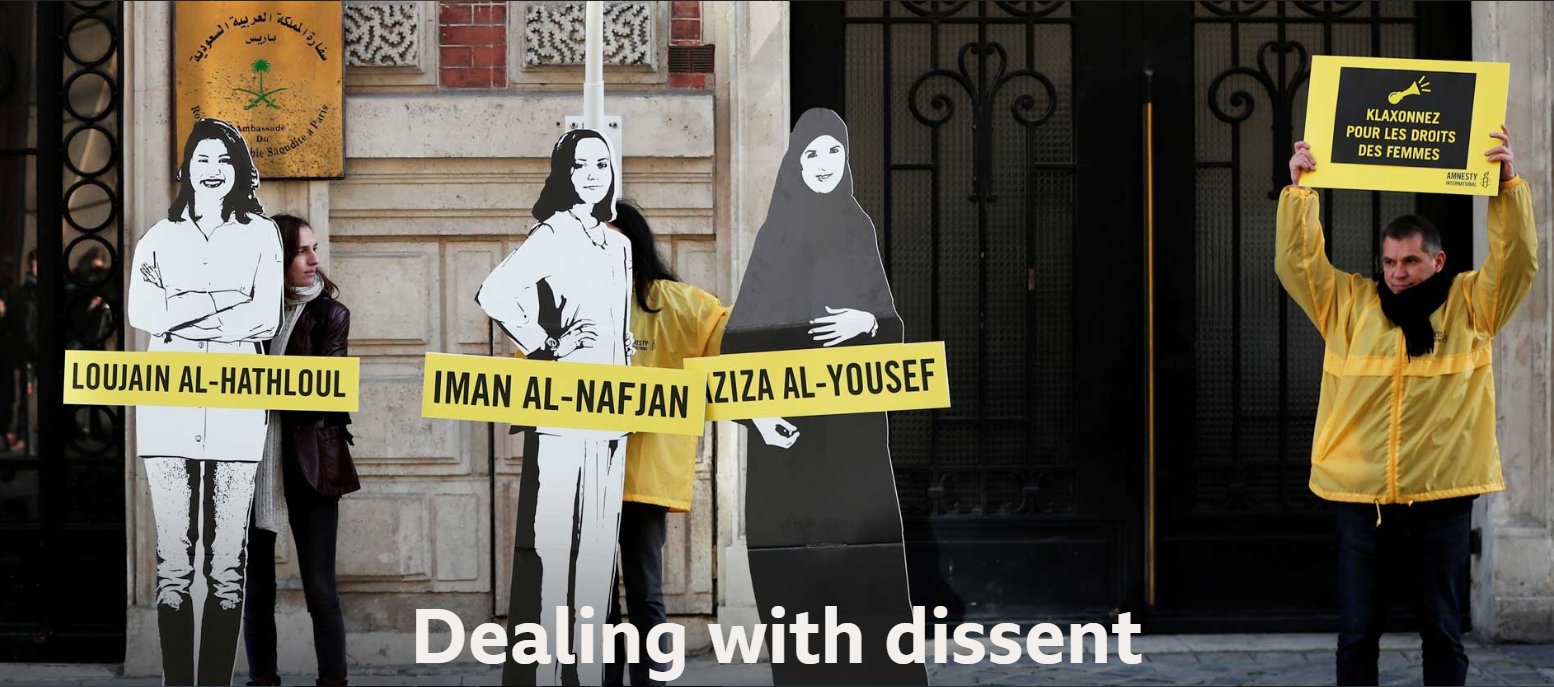

Dealing with dissent

Human rights activists outside the Saudi embassy in Paris

If one were to characterise MBS’s attitude to the seismic social and economic reforms he is pushing through, it would be: “It’s either my way or the highway.” Put simply, MBS doesn’t do dissent.

Bloggers, clerics, women’s rights protesters, people from both the liberal and conservative ends of the spectrum, have all ended up getting arrested under draconian catch-all laws that stifle all dissent or discussion.

In its annual report, Human Rights Watch revealed that “the Saudi authorities stepped up their arbitrary arrests, trials and convictions of peaceful dissidents and activists in 2018, including a large-scale coordinated crackdown against the women’s rights movement”.

But isn’t this the same ruler who finally gave Saudi women the right to drive? Well, yes. But the point is, say observers, that MBS wants the change to come from the top down, from the Royal Court.

Any suggestion of the law being changed or reforms being enacted as a result of some popular street-level movement, however small, is deemed a dangerous one in a country that has no political parties or opposition.

Take Loujain al-Hathloul, for example. Educated, intelligent, active on social media, she spent her 30th birthday in prison in Jeddah this past July.

Her family say her only crime was to campaign for Saudi women to be allowed to drive and for an end to the restrictive guardianship system that gives men enormous control over the lives of their wives and female relatives.

Both laws have now been changed for the better - women can drive and the guardianship system has been relaxed.

But al-Hathloul and several other female activists appear to have annoyed the Saudi leadership by publicly pushing for something that MBS would prefer to take the credit for. You do not try to force the pace of change in the kingdom.

Al-Hathloul was first arrested in in 2014 after driving her car from the UAE into Saudi Arabia. In March 2018, while driving legally in the UAE, she was reportedly pulled over by a convoy of blacked-out vehicles, arrested and rendered back to Riyadh where she was briefly detained. In May 2018 she was again arrested in the wider crackdown.

Al-Hathloul and other female activists say they have been tortured and spent time in solitary confinement.

'During the first three months, during the sessions of interrogations, they were subjected to acts of torture and other ill treatments that included flogging, electric shocks, sexual harassment,' says Lynn Maalouf, from Amnesty International.

The Saudi authorities have denied that any torture takes place in their prisons or police cells and promised to investigate. But instead of their alleged abusers facing charges, the women themselves were charged.

Walid al-Hathloul, Loujain’s brother, who lives outside the country, says the prosecutor never investigated the claims of torture. “We sent three complaints and they never responded. The prosecutor reached his conclusion based on the Saudi Human Rights Commission and not on their own (independent) investigation.” Walid al-Hathloul is also pressing for Saud al-Qahtani to be investigated, with Loujain alleging he personally took part in her abuse in detention.

Loujain al-Hathloul

Loujain al-Hathloul

Aziza al-Yousef

MBS was challenged on the issue of mistreatment of women prisoners in his 60 Minutes interview. He promised to personally investigate.

More than 30 countries have called on Saudi Arabia to release the activists, some of whom have subsequently been allowed out on bail, and both the US and British governments say they have raised the issue at the highest level. Yet in August 2019, Loujain al-Hathloul’s family said that security officers had visited her in jail and put pressure on her to sign a statement denying her relatives’ claims that she had been tortured in custody. She refused.

Other detained female activists include Samar Badawi, arrested after challenging the guardianship laws, Iman al-Nafjan, blogger and campaigner for women’s right to drive and Aziza al-Yousef, retired university professor who has helped women escape domestic abuse.

But at home there is not much public sympathy for the women’s plight. There is little if any media coverage inside the kingdom and a trolling campaign saw them branded unpatriotic traitors. The authorities claimed they had passed secrets to enemies of the state.

There are also many cases of male activists being detained and punished.

In September 2018, Saudi prosecutors announced a penalty of five years in prison and a fine of three million riyals (£600,000) for anyone caught sharing anything on social media deemed by the authorities to affect public order or morals. Yet MBS is unapologetic about his intolerance of dissent. In interviews he has admitted that large numbers of people are behind bars but said that this is somehow a necessary price to be paid when you are driving through such a sweeping reform programme. So how exactly did a man who was virtually unknown six years ago come to be arguably the most powerful ruler in the Middle East?

Son of the land

Born on 31 August 1985, Mohammed bin Salman grew up, like nearly all the estimated 5,000 senior Saudi princes, in a closeted world of extraordinary comfort and privilege.

As one of 13 children, his childhood was a walled and well-guarded Riyadh palace in the Madher neighbourhood. Servants, cooks, drivers and other expatriate employees catered to his every whim.

One of those who tutored him in his early years, in the mid-1990s, was Rachid Sekkai, who now works for the BBC. He has described being collected from home each day in a chauffeured car to bring him to the palace.

“Once through the heavily guarded gates, the car would wind past a series of jaw-dropping villas with immaculate gardens maintained by workers in white uniforms,” he told BBC Arabic. “There was a car park filled with a fleet of exclusive luxury cars.”

Some accounts have talked of MBS being a studious pupil, always taking careful notes, but Sekkai says he found him more interested in spending time with palace guards than following his lessons.

“He seemed to be allowed to do as he pleased,” he said.

Offered the chance by his father to study abroad in the US or Britain, as so many of his peers had done, MBS declined. Instead, he gained a bachelor’s degree in law at King Saud University. This unusual decision, say observers, has both helped and hindered him.

For many Saudis, an intensely patriotic nation, his exclusively Saudi upbringing makes him a traditional “son of the land”, someone they can identify with. But the downside is that for years MBS’s English was poor and he has never really gained the kind of innate understanding of Western mentality that so many other princes acquire.

King Saud University, where MBS was a student

In a country where it’s not uncommon for men to have up to four wives, MBS chose to have only one. He married his cousin - a common practice - Princess Sara bint Mashur bin Abdulaziz al-Saud in 2009 and they have two sons and two daughters. When it comes to his own family, MBS is intensely private.

So how did he move so quickly from being an obscure graduate of law and one of thousands of Saudi royals to becoming the all-powerful crown prince he is today?

The answer lies in an extraordinary blend of Machiavellian power politics, paternal patronage and sheer force of character.

MBS's personal superyacht, the Serene, bought for 500m euros

When MBS was about 23, soon after he graduated close to the top of his class, his father began preparing him for a senior role.

MBS worked in his father’s office, shadowing him in his work as governor of Riyadh. The attentive young MBS saw how Prince Salman settled disputes and forged compromises, effectively learning the art of Saudi statecraft.

In 2013, at the age of just 27, MBS was made head of the crown prince’s court, effectively a gateway to power and influence. The next year he was promoted to cabinet minister.

Then in 2015, MBS’s career moved into high gear.

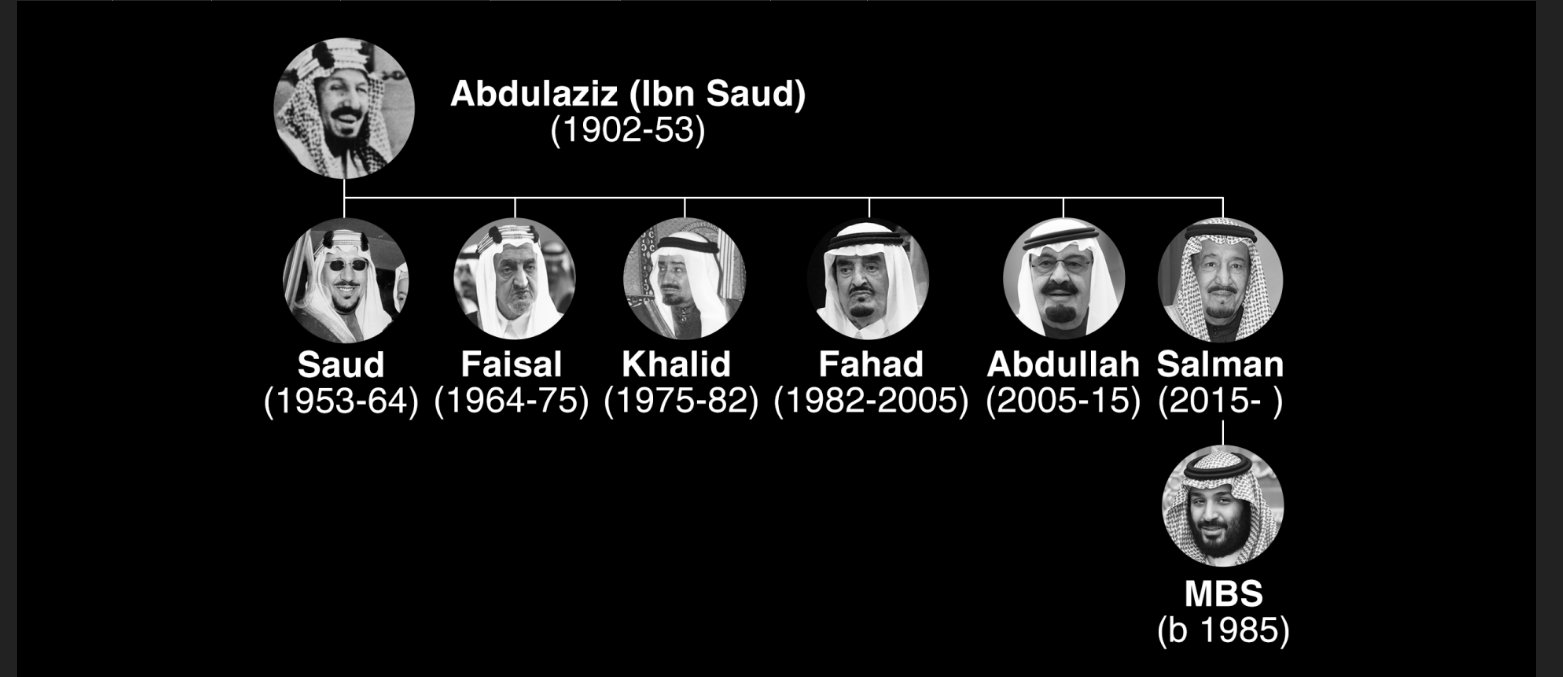

The Saudi royal line of succession from Abdulaziz to Salman

When King Abdullah died in January of that year, he was succeeded by his half-brother Salman from the powerful Sudairi branch of the family. The new king, already nearly 80 when he took the throne, was now free to favour exactly who he chose. His favourite son Mohammed - MBS - was promptly made minister of defence as well as secretary-general of the Royal Court.

By now Saudi Arabia was facing a mounting crisis on its southern border. In Yemen the Houthis, a group of tribesmen from the northern mountains, had marched on the capital Sanaa, ousted the elected president and his government and had seized control of almost the entire, more populated, western half of the country.

The Houthis’ ideological and religious links with Iran rattled Saudi nerves. In March 2015, without consulting several key princes and giving almost no warning to Saudi Arabia’s allies, MBS pulled together a coalition of 10 nations and led his country into an air war against the Houthis.

The official aim was to restore the ousted but UN-recognised government in Yemen. The unstated aim was to send a blunt message to Iran - Saudi Arabia was not going to allow an Iranian-backed proxy militia to take over its southern neighbour. This was supposed to be a quick and decisive military intervention against a ragtag army of rebels armed with Soviet-era weapons.

Instead, it has turned into a quagmire that is bleeding Saudi blood and treasure as well as devastating Yemen.

Saudi border guard facing Yemen

The Saudi-led coalition has made precious little progress on the ground. Nearly five years on, Yemen has been pulverised by war, with thousands killed. Malnutrition, cholera and disease are rife, while an estimated 20 million people, about two-thirds of the population, are in need of aid.

But at home, the beginning of the war won MBS instant popularity. He had no military experience whatsoever but Saudi TV showed a “warrior prince” acting decisively in his country’s interests.

Western nations were initially highly supportive. The US provided intelligence and refuelling as well as hardware. Britain provided logistical and technical support as well as advice to the Saudi armed forces on equipment sold to them by BAE Systems. Two RAF squadron leaders were stationed inside the Coalition Air Operations Centre in Riyadh to monitor Saudi targeting procedures, although the MoD insists they did not choose targets.

Royal Saudi Air Force targeting has turned out to be frequently flawed.

Scenes from the war in Yemen

Hospitals, funerals, residential areas and school buses have been blasted to smithereens, alongside legitimate military targets. The UN estimates that the majority of civilian casualties in Yemen have been caused by Saudi-led airstrikes. The Saudis have been accused of using cluster bombs on civilian areas.

The Houthis too are accused of war crimes, laying mines indiscriminately, employing child soldiers, shelling houses and withholding aid. By September 2019 the Houthis had - according to the Saudis - fired more than 260 ballistic missiles and 50 explosive drones across the border. Yet this is dwarfed by the overwhelming air superiority of the Saudi-led coalition.

Led by human rights groups like Amnesty International, there has been a growing chorus of Western public dismay at the casualties in Yemen.

In the space of five years, Yemen has become the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

Power and perception

Ritz-Carlton Hotel, Riyadh

On 20 June 2017 something happened, behind the gilded doors of a royal palace in Mecca, that effectively changed the course of Saudi history. The crown prince at the time, Mohammed bin Nayef, was summoned by the king and ordered to step aside in favour of his much younger cousin: MBS.

For years the veteran Prince Mohammed bin Nayef had been a safe pair of hands. During the 2000s, as head of counter-terrorism and later interior minister, he had masterminded the defeat of a serious insurgency by al-Qaeda. He was liked and trusted by the Americans and, although certainly not a dynamic figure, he was seen as a steady choice as next in line to the throne.

But the word was that he had never fully recovered from a failed assassination attempt in 2009 when al-Qaeda managed to smuggle a suicide bomber right into the same room as him.

King Salman had made his decision as to who he wanted to succeed him and it was his favoured son, MBS.

In Saudi Arabia the king’s power is absolute - there was no debate, no resistance. Mohammed bin Nayef has since vanished completely from public life.

Former Crown Prince Mohammed bin Nayef has disappeared from public life

MBS and his father had pulled off what amounted to a spectacular and bloodless palace coup.

Highly ambitious and determined to reshape the country, MBS promptly set out to cement his hold on power.

Late in the evening of Saturday 4 November 2017, orders went out to arrest about 200 prominent princes, business leaders and others. There were no charges, no prison cells - instead they were incarcerated in Riyadh’s luxurious Ritz-Carlton Hotel, in some cases for months.

It was billed as an anti-corruption drive and the hotel’s new “guests” were ordered to hand over billions of riyals in alleged ill-gotten gains as the price for their freedom.

But critics of MBS contend this was less about corruption, instead it was a naked power play to neutralise anyone who could possibly challenge him.

At the same time MBS moved against senior princes from the late King Abdullah’s once-powerful branch of the family. He has since brought all three elements of the country’s defence and security forces under his control: the National Guard, the Ministry of Interior and the Military. MBS’s power appears absolute.

The Ritz-Carlton arrests sent shockwaves through the business world and rattled foreign investors. How could people know who it was safe to do business with? Who would be next?

The Red Sea port of Jeddah: Many Saudis still live in poverty

Yet among a great many Saudis the move was applauded. The country may be the world’s biggest oil producer but a surprisingly large number of its citizens live in poverty, especially in the south. The sight of so many previously untouchable merchants and princes being “shaken down” earned MBS even more followers at home.

Another key plank in his domestic popularity is his efforts to transform the Saudi economy by diversifying away from oil, turning the country into an investment powerhouse and providing meaningful jobs for millions of under-employed young Saudis.

The Vision 2030 plan is nothing if not ambitious. It envisages a future, not far off, where Saudi Arabia has become the global hub connecting Europe, Asia and Africa.

It includes a US$64bn fund to develop entertainment and aims to create a million new jobs in domestic tourism.

April 2016: MBS launches Vision 2030 in Riyadh

But here too the dark spectre of the Khashoggi murder has cast a shadow. Some - but not all - foreign investors have scaled back or cancelled their interest in supporting the crown prince’s plans, wary of being associated with someone still under international suspicion for his alleged involvement in that murder.

But Vision 2030 is going ahead and it includes an extraordinary, futuristic project called NEOM - standing for Neo-Mustaqbal or New Future.

Far up in the northwest corner of Saudi Arabia, where the balmy waters of the Red Sea wash up against the shores of Egypt, Jordan and Israel, plans are afoot to create a 21st Century megacity.

The front page of the official NEOM website

Where today there is little more than wind-blasted sand and black, volcanic rock, a searing desert where TE Lawrence and an Arab army fought the Turks during World War One, there is planned to be a US$500bn cross-border project spanning 26,000 sq km.

NEOM is intended to be a city dominated by drones, driverless cars, robotic assistants, artificial intelligence, solar powered greenhouses, the “internet of things” and biotech.

Officially it’s due to be up and running by 2025. But some economists have their doubts.

“No, it’s just not realistic,” says one. “NEOM was always a fantasy and it’s indicative of the distance between ambition and reality that characterises the way MBS looks at the world.”

Yet MBS is so confident in the project I am told he believes it will one day rival Palo Alto, the home of tech in California.

Saudi Arabia does not have a shining track record where new, purpose-built cities are concerned.

“Take King Abdullah Economic City,” said another Gulf economist recently. “It was supposed to have two million people in it by 2020. It has just 8,000. So no, he probably can’t deliver on this economic dream.”

Progress on the King Abdullah Economic City is said to have been disappointing

NEOM is still likely to be built, but at a slower pace than planned. Too much is at stake now. But whether it can attract foreign investment and generate vast numbers of domestic jobs is highly questionable.

Aftermath

In September 2018, Boris Johnson took a three-day, all-expenses paid trip to Saudi Arabia, costing his hosts £14,000, all of which was declared to Parliament. Johnson knew nothing about it, but this was just two weeks before the murder of Jamal Khashoggi.

March 2018: MBS with Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson in Downing Street

Before that time, the arrests of activists were little reported outside Saudi Arabia, and MBS’s stock among Western leaders was running high.

Afterwards, such a visit would be almost unthinkable.

Now, in the West where he was once feted as a visionary reformer and trailblazer for social reform, he is now largely shunned, at least in public.

“The Khashoggi murder propelled Saudi Arabia into The Killers Club,” said one Gulf commentator, who, like so many, has asked not to be named . “It appeared to put MBS into the same category as Gaddafi, Saddam and Assad. This is a club that the Kingdom never used to be a part of.”

Privately, business with Saudi Arabia continues apace - the Saudi economy is simply too big and the contracts too lucrative for Western businesses to ignore. President Trump remains a steadfast ally.

Congress has tried unsuccessfully to halt multi-billion arms sales to the Kingdom but President Trump has overruled them, on both strategic and financial grounds.

The enormous Saudi market, coupled with its perceived strategic value as a bulwark against Iranian expansionism, mean that Western government criticism will probably always be tempered. But already, the obvious Western disapproval of Saudi Arabia’s human rights shortcomings has hit a sensitive nerve in Riyadh.

The Saudis are trying to shift the dial. The new envoy to Washington is Princess Reema bint Bandar al-Saud, the country’s first ever female ambassador and a sophisticated businesswoman who has spent years living in the US.

Reema will be the public face of Saudi diplomacy in a capital where congressmen and others are now seriously questioning the validity of the US-Saudi partnership.

Princess Reema bint Bandar al-Saud, ambassador to Washington

But the Saudis are also actively exploring relationships with other strategic partners - with Russia, China and Pakistan - none of whom raise awkward questions about Saudi human rights.

Over the course of the past 12 months some damning statements and allegations have bubbled up to the surface - notably from US intelligence officials and UN special rapporteur Agnes Callamard - that remind the world that Western suspicions still fall on MBS as having personally ordered the Khashoggi murder. She remains adamant that he must ultimately be held accountable for the murder.

Yet at home, MBS’s stock is riding high. “Talk to anyone aged 16-25,” said one Gulf commentator, “and they see him as a hero. They love the socio-cultural changes he’s bringing, pushing back the power of the religious fundamentalists.”

There is little sign that under MBS, Saudi Arabia is about to make any real moves towards democracy. Any public questioning, let alone criticism, of the ruling family and its policies carries the risk of imprisonment.

For years MBS has enjoyed the absolute backing of his father, King Salman, and there are no obvious challengers to his rule. Within MBS’s Royal Court circle there is a view that the storm in the West over his alleged role in the Khashoggi murder will eventually blow over. They are probably right.

In many respects, MBS is Saudi Arabia. He is no democrat, he is no political reformer - to many, he is simply a dictator. But MBS is unquestionably an economic and social moderniser. And at 34 years old he knows that when the king dies he could well end up ruling the largest country in the Middle East not just for a decade, but for the next 50 years.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

CREDITS AUTHOR: Frank Gardner PHOTOGRAPHY: Alamy, Getty Images, Reuters, Shutterstock, Frank Gardner GRAPHICS: Debie Loizeau & Sana Jasmeni ONLINE PRODUCTION: Ben Milne EDITOR: Finlo Rohrer All images subject to copyright. Built with Shorthand. Explore the BBC Home News Sport Reel Worklife Travel Future Culture Music TV Weather Sounds Terms of Use About the BBC Privacy Policy Cookies Accessibility Help Parental Guidance Contact the BBC Get Personalised Newsletters Advertise with us Ad choices Copyright © 2019 BBC. The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read about our approach to external linking.

----------------------------------------------------------

Homepage Accessibility links Skip to contentAccessibility Help Sign in Home News Sport Reel Worklife Travel Future Culture More Search the BBC Search Search the BBC BBC The note-taker Khashoggi A softer Saudi? Dealing with dissent Son of the land Power and perception Aftermath