Date: 2026-03-04 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00013460

Country / Namibia

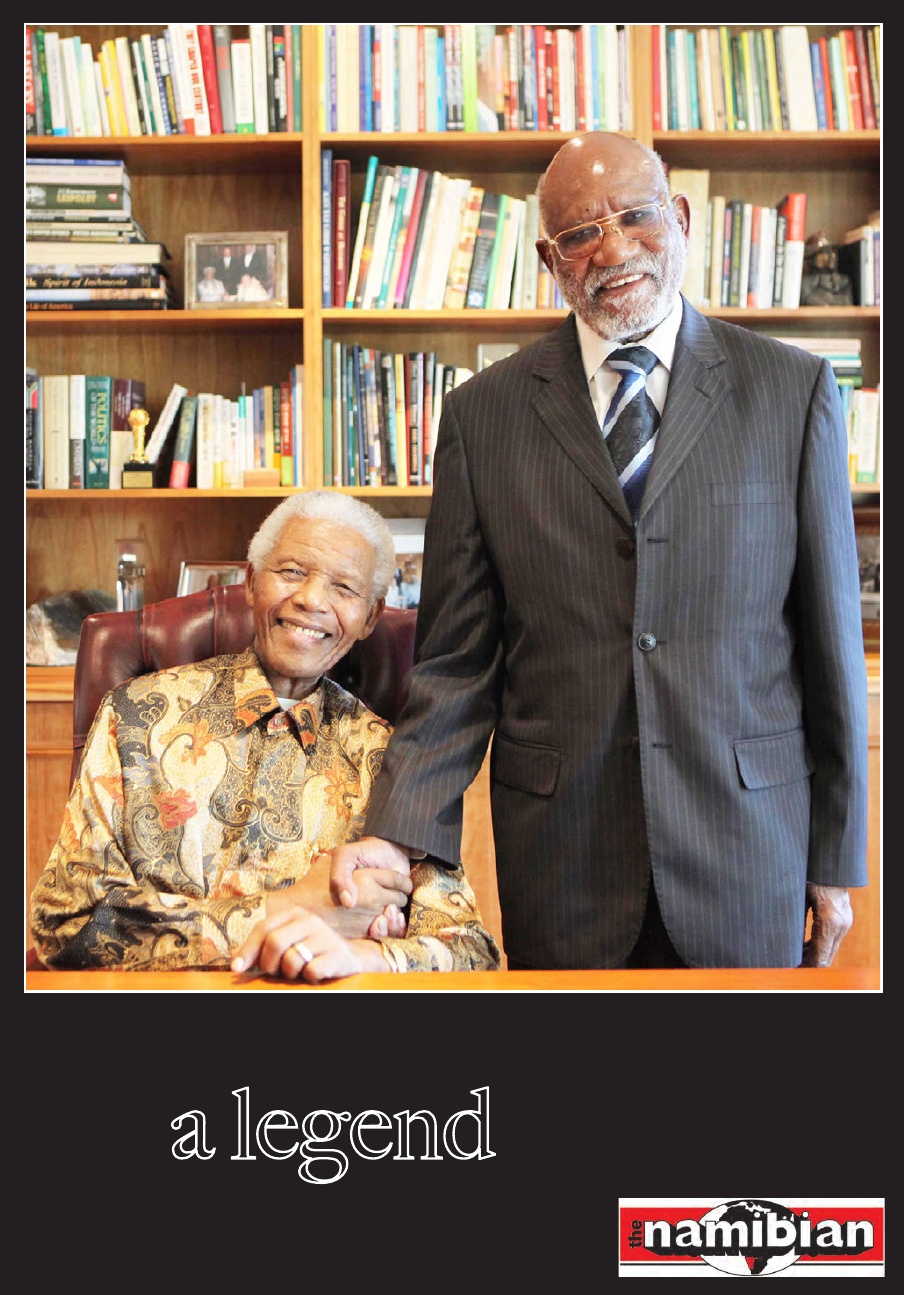

People / Andimba Toivo ya Toivo

Tribute to a Namibian icon: Andimba Toivo ya Toivo

Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

The Conversation

Search analysis, research, academics…

Academic rigor, journalistic flair

Arts + CultureEconomy + BusinessEducationEnvironment + EnergyEthics + ReligionHealth + MedicinePolitics + SocietyScience + Technology

Tribute to a Namibian icon: Andimba Toivo ya Toivo

On June 9, 2017 Namibia became poorer. A moral beacon left the people, for whose freedom he lived most of his 92 years. Active until the end, Andimba (Herman) Toivo ya Toivo had just returned from a trip to Robben Island with his fellow inmate Helao Shityuwete – one of the other truly selfless, most underrated freedom fighters. Hours later he fell asleep forever at home.

Ya Toivo had been a torchbearer of the determination for freedom from foreign rule. He embodied a generation – many of whom left behind the values they claimed had guided their struggle after independence. In contrast, Ya Toivo remained loyal to what made him the personification of the desire to live in an independent country governed by and for its people in decency.

The loss of Ya Toivo should encourage others to become the torchbearers of his values.

Road to Robben Island

Brought up in the northern Namibian region then called Ovamboland, he was trained as an artisan and volunteered to fight for South Africa in World War II. After leaving school in the early 1950s he worked on contract in Cape Town where he became politically aware through African National Congress (ANC) activists.

He started to mobilise his fellow Namibian contract workers. These were Namibians from the northern parts of the territory who were contracted for periods of time to work (without their families) in mines and industry. They were restricted to the workplace and accommodated in compounds if they weren’t living as domestic workers with their employers.

He founded the Ovamboland People’s Congress, which demanded the abolition of contract labour and an end of South African administration over his country. In 1958 he managed to dispatch a tape-recorded petition to the United Nations and was subsequently deported back to Ovamboland. There he became involved in the formation of the South West African People’s Organisation (Swapo).

Ya Toivo helped the first liberation fighters who had been trained abroad to prepare for the armed struggle. On August 26, 1966 the first military encounter occurred with the South African regime. Ya Toivo and hundreds of others were arrested.

He was put to trial in Pretoria along with Eliaser Tuhadeleni (as accused No 1) and 34 others. Ya Toivo’s speech from the dock on February 1, 1968 became a lasting document of Namibian aspirations for freedom:

We are Namibians and not South Africans. We do not now, and will not in the future, recognise your right to govern us, to make laws for us in which we have no say; to treat our country as if it were your property and us as if you were our masters. We have always regarded South Africa as an intruder in our country. This is how we have always felt and this is how we feel now, and it is on this basis that we have faced this trial.

Thanks to international pressure, the accused were spared the death penalty. Ya Toivo and several others were sentenced to long imprisonment of which they served up to nearly 20 years.

On Robben Island, Ya Toivo’s defiance, stubbornness and resilience made him the most respected among the Namibian prisoners, who developed close ties with the ANC inmates. Andimba and Madiba (Nelson Mandela’s clan name) had more in common than a striking similarity of the letters in their names. They remained friends for the rest of their lives. As remembered by Denis Herbstein:

In prison Toivo was unbending, seizing every opportunity to show his disdain for his jailers. A fellow prisoner described the scene when Toiva [sic] responded to his treatment by a young warder: Andimba unleashed a hard open-hand smack on the young warder’s cheek, sending [his] cap flying and [the warder] wailing (in Afrikaans), ‘The kaffir hit me’. The inevitable spell of solitary confinement followed. When Toivo was released in March 1984, short of his full term, he refused to leave his fellow prisoners and had to be coaxed out of his cell.

Into exile and Namibian independence

Back home in Namibia, Ya Toivo refused to accept a South African initiated transitional government and left for exile. The Swapo leadership created the post of secretary-general for him, a niche to keep him away from the consolidated inner circle of power. He humbly accepted what was mainly a symbolic position to represent Swapo internationally without influencing its policy.

He soon met the US-American lawyer Vicky Erenstein. They married a week into Independence in 1990. In 1993 they became the parents of twin daughters Mutaleni and Nashikoto. They also adopted two of Ya Toivo’s nephews. The children remember their father as youthful, “fun-loving, yet strict, attentive, playful and loving”.

He raised them to be loyal to fundamental principles such as honesty and modesty.

Maybe his biggest moral challenge (and failure) was when Swapo gave him the task in 1989 to monitor the release of several hundred so-called ex-detainees who had survived a Swapo purge in exile. During the 1980s thousands were kept near the southern Angolan town of Lubango where they were tortured by a terror regime of “securocrats”. Many were executed or didn’t survive. Ya Toivo’s credibility was abused to downplay – if not to justify – the atrocities. He accepted the dubious role and never openly corrected the injustice and violation of human rights he certainly condemned.

On the evening of March 20, 1990, before the official independence ceremony at midnight, the Swapo leadership gathered for a banquet with local VIPs in the German club in central Windhoek. Not so Ya Toivo. He spent most of the evening with local activists and members of the international solidarity movement who had come together at a venue on the outskirts of the city.

Loyalty to true liberation

Since Namibian independence Ya Toivo served three terms in cabinet as minister. As before, he put the party’s interest above his personal ambitions. Or rather, he acted in accordance with what he understood as being in the best interests of the country.

Power politics were a strange thing for him. What mattered were the party and the people. But he realised that the two are not identical. As a result, he displayed the wisdom one would expect from a true leader. Speaking for the last time in the National Assembly on March 16, 2005 he reminded his comrades:

Being a member of parliament or even a minister should not be seen as an opportunity to achieve status, to be addressed as ‘honourables’ and to acquire riches. If those are your goals, you would do better to pursue other careers.

Ya Toivo remained critically observant of the limits to liberation. As late as 2014 he commented on the values of South Africa’s Freedom Charter and the current leadership of the governing ANC. He quipped in a video recorded interview, that the people did not support the struggle for them just to fill their pockets and to loot the country.

Just as the ANC needs moral guardians who will enforce its core values to save its brand, so does Namibia’s Swapo.

If there is a positive meaning to patriotism – all too often abused for inventing heroic narratives by those holding political power and celebrating themselves – then it can be identified with Toivo ya Toivo, a true Namibian patriot departed from this world.

Hamba Kahle, Andimba. You left behind a lasting legacy to the Namibian people who share your belief in true liberation as emancipation from greed and social injustice and a life in human dignity.

=========================================================

Author

Henning Melber

Extraordinary Professor, Department of Political Sciences, University of Pretoria

Disclosure statement

Henning Melber joined SWAPO in 1974 and met Andimba Toivo ya Toivo for the first time in 1984.

Partners

University of Pretoria

University of Pretoria provides funding as a partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

View all partners

Republish this article

Republish Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons license.