Date: 2026-01-18 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00013404

The Trump Presidency

Economy in Disarray

The Finance 202: The deficit is getting worse -- and it's making everything tougher for Republicans

Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

A tipsheet navigating the intersection of Wall Street and Washington. Not on the list? Sign up here.

The Finance 202

Your economic policy briefing

The Finance 202: The deficit is getting worse -- and it's making everything tougher for Republicans

item.bylineText

The Treasury Building. (AP /J. Scott Applewhite)

The federal government is running out of money. By early to mid-October, the Treasury will be scraping the till to pay the country’s creditors.

Sometime between now and then, members of Congress need to approve an extension of the federal government’s borrowing authority, raising the so-called debt ceiling. Otherwise, the U.S. will face the specter of its first-ever default, forced to choose between paying bondholders and meeting other obligations, like pensions for veterans.

The debt ceiling hike is a could-be, should-be straightforward piece of business, allowing the Treasury to cover bills for spending that the Congress itself has already wrung up. But conservative Republicans in the Obama-era began demanding major concessions as the price of their support. Staring down the barrel of a default in the summer of 2011, policymakers averted disaster by agreeing to a package of $1.2 trillion in automatic cuts to be split evenly between defense and discretionary spending and imposed over a nine-year period that ends in 2021.

Those cuts have helped rein in the budget deficit. But it’s on pace to swell to $693 billion this fiscal year, the Congressional Budget Office said Thursday, clocking in at 3.6 percent of gross domestic product. That’s the government’s widest gap between collections and outlays since 2013, when the spending caps first took effect. In the same report, the CBO said Congress has until mid-October to raise the debt ceiling or it will risk default.

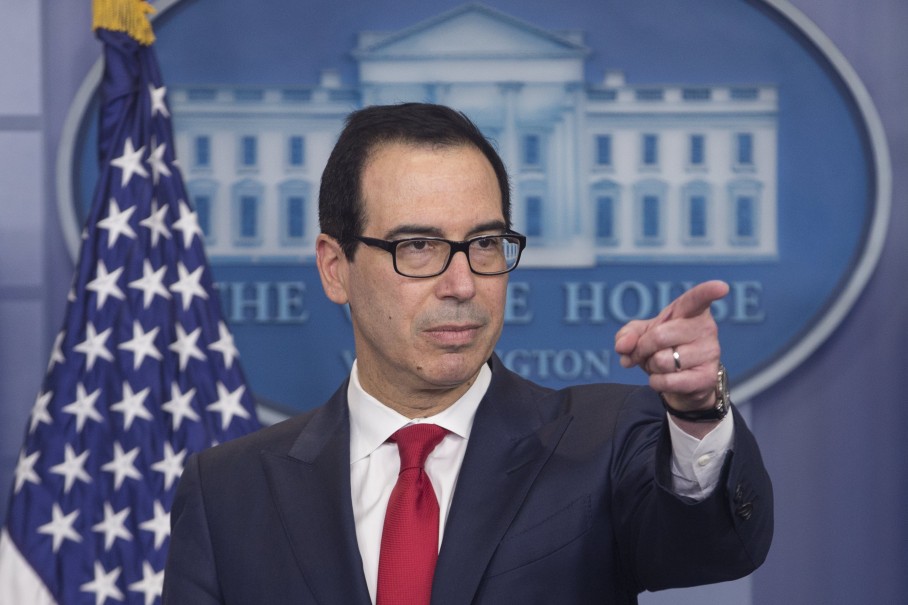

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin. (EPA/Michael Reynolds)

The darkening deficit picture forms the backdrop for an increasingly tense intraparty debate now unfolding within Republican ranks on Capitol Hill. The party in power is struggling to reach agreement on a budget. Defense hawks want to bust the spending caps for the Pentagon while ultraconservatives are demanding cuts to entitlement programs that have moderates threatening to sink the package. The GOP needs to reach consensus on spending levels in part because the budget resolution will also allow them to fast-track an overhaul of the tax code.

Oh, and the reason the deficit is splitting its seams this year? As my colleague Damien Paletta reports, the primary driver has been a surprising shortfall in the government’s tax collections. And that, in turn, appears to be the result of wealthier people sitting on their checkbooks in expectation of lowered rates once congressional Republicans approve a rewrite of the tax code.

So to recap: People aren’t paying their taxes because they’re waiting for their tax breaks, which is swelling the deficit, which is likely to exacerbate Republican infighting over the budget, which Republicans need to resolve in order to deliver people their tax breaks. Which is what it might look like if the Laffer curve tried to swallow itself.

The budget could take on added significance as a vehicle for a debt ceiling hike, an option both conservative and moderate House Republicans have been talking up in recent days, as my colleague Mike DeBonis noted:

Typically, the White House would help mediate such an impasse. On Thursday, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin told reporters that Congress should lift the debt ceiling as quickly as possible. 'For the benefit of everybody, the sooner that they do this, the better,” he said. Besides statements Mnuchin has made in congressional testimony and in various other public appearances and interviews, however, the administration has not been heavily engaged on the issue behind the scenes with members of Congress.

That may need to change, if congressional Republicans aren’t able to forge their own breakthrough. But it’s tough to imagine President Trump speaking with much credibility on the urgency of action. Then-President Obama faced questions about his standing on the subject as the debate around the 2011 debt ceiling began heating up, since he’d voted against extending the feds’ borrowing authority as a young senator in 2006.

Five years later, having moved up Pennsylvania Avenue, Obama owned up to grandstanding, telling ABC News, “As president, you start realizing, you know what, we, we can't play around with this stuff. This is the full faith and credit of the United States. And so that was just an example of a new senator making what is a political vote as opposed to doing what was important for the country. And I'm the first one to acknowledge it.'

Before running for office, Trump made clear he believed raising the debt ceiling was a mistake:

As a candidate, Trump endorsed using the debt limit as leverage, telling Fox News in a 2015 interview that he 'would be very, very strong on the debt limit. And I would be asking for a very big pound of flesh if I were the Republicans.' Until earlier this month, congressional Republicans were unsure who from the administration spoke for Trump on the matter, since Mnuchin was advocating a clean debt ceiling hike while Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney backed attaching spending reductions to it. Pressed by GOP leaders, Trump indicated Mnuchin is taking the lead for the White House.

You are reading The Finance 202, our must-read tipsheet on where Wall Street meets Washington.