Date: 2025-12-28 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00013038

Initiative

CISL ... Rewiring the Economy

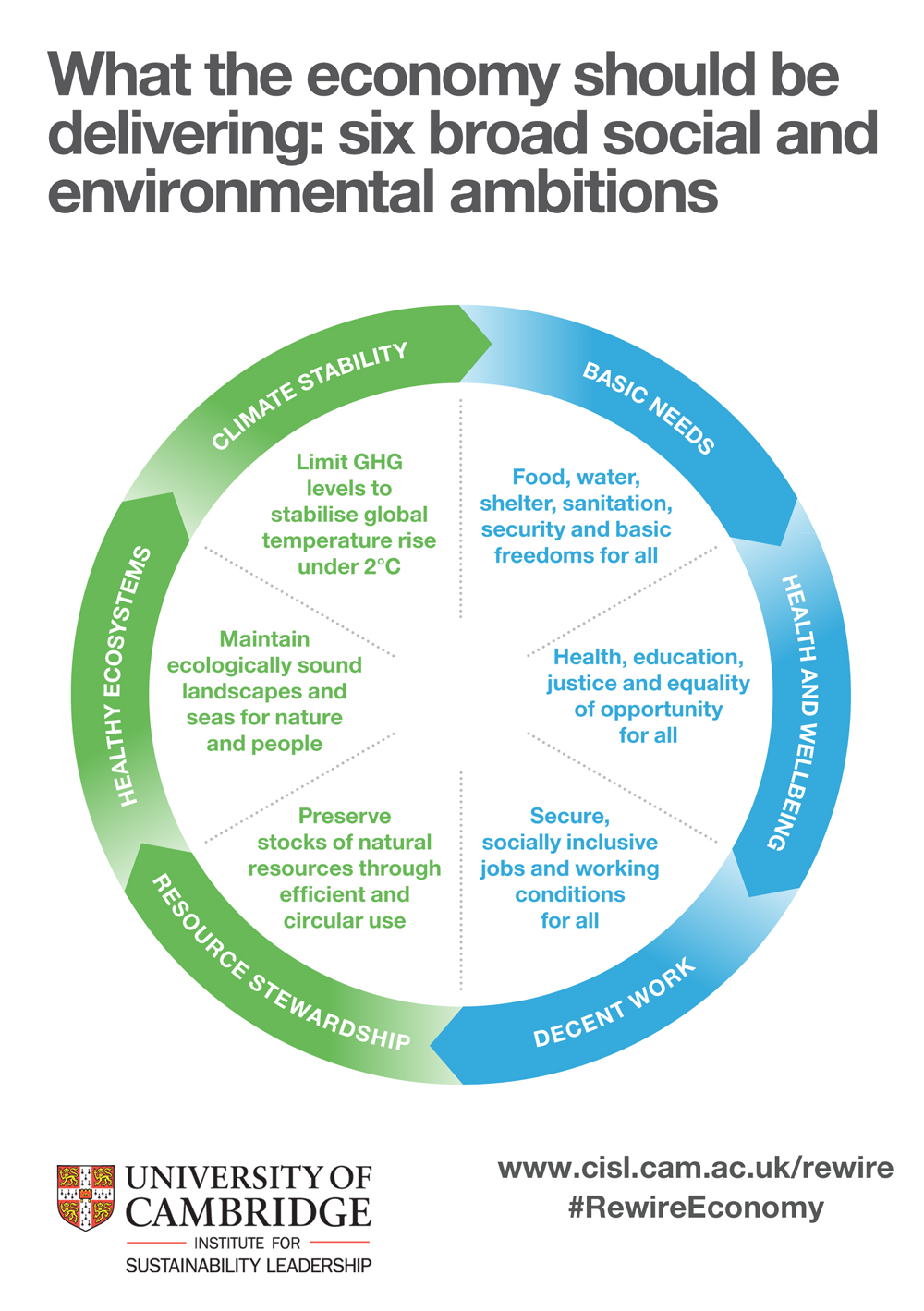

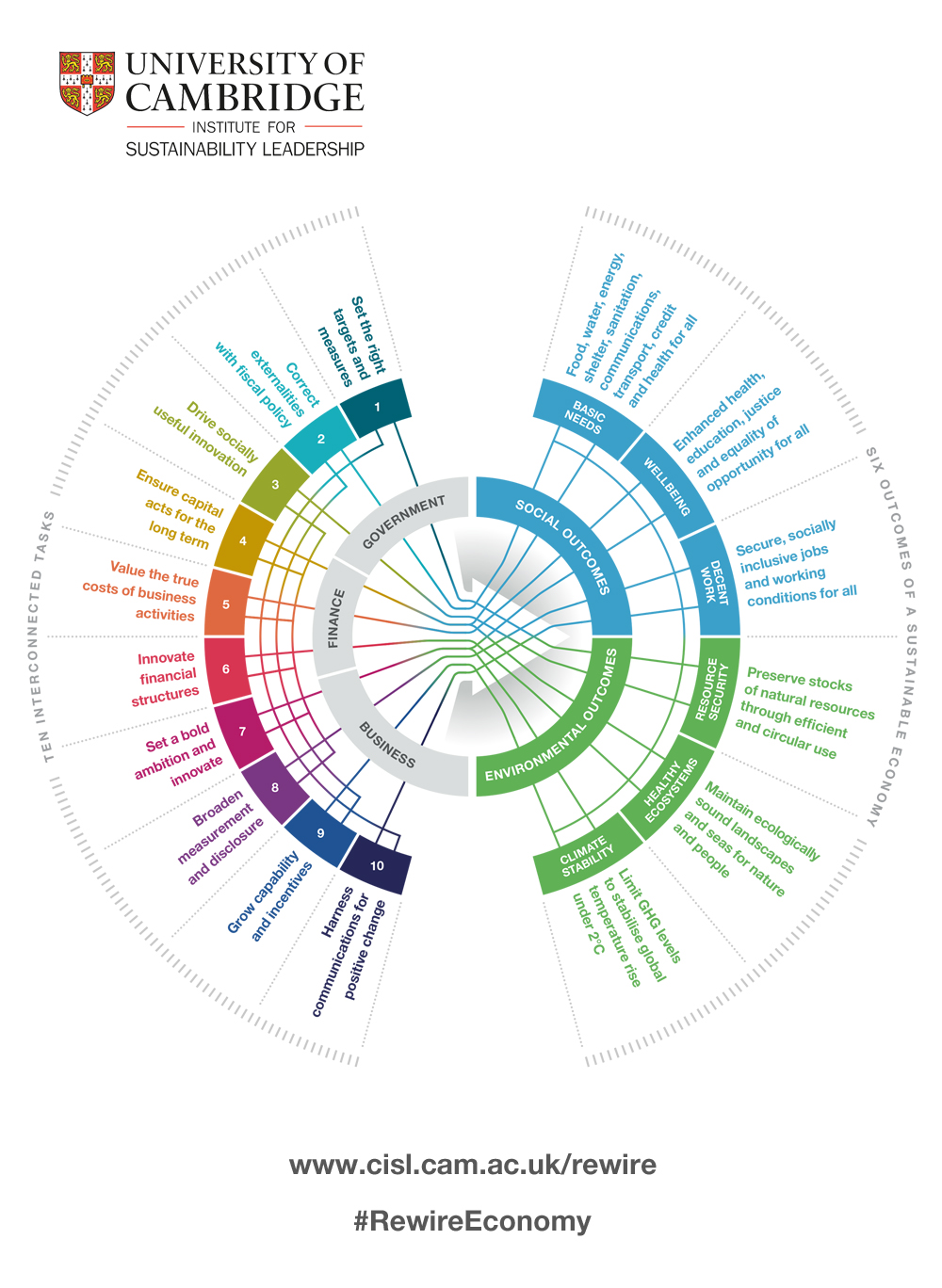

Rewiring the Economy is CISL’s ten-year plan to lay the foundations for a sustainable economy.

Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

Rewiring the Economy is CISL’s ten-year plan to lay the foundations for a sustainable economy.

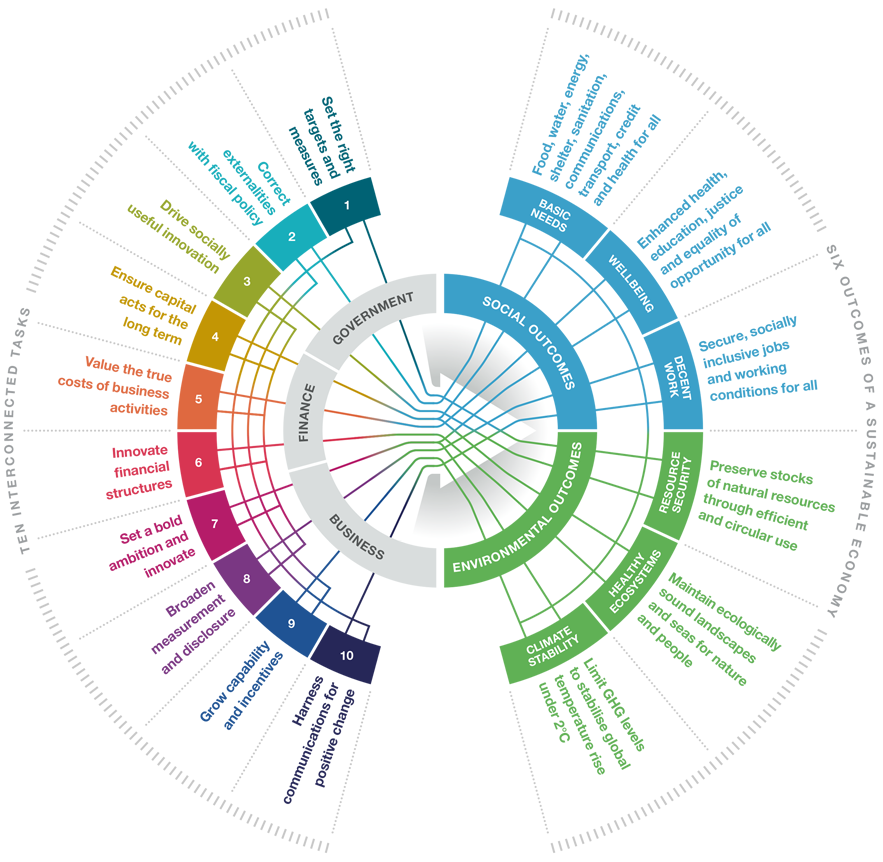

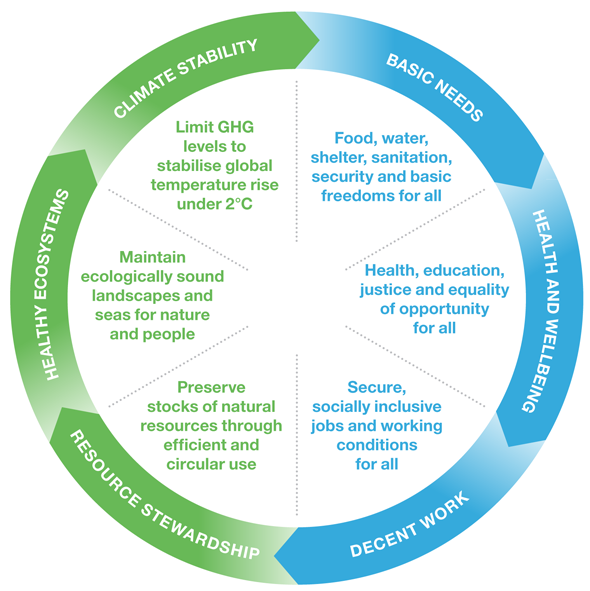

It has a simple logic: six sustainability ambitions to be delivered by three economic actors (business, government and finance) via ten interconnected tasks.

Rewiring the Economy starts from the principle that the economy can and should be delivering the outcomes demanded by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). By working together as partners, three key actors in the economy – business, government and finance – are identified to take responsibility for achieving this aim. A set of ten interconnected tasks are offered to guide the structural and cultural changes that will be necessary in the economy to do this.

The plan is a strategic compass bearing for business, government and finance leaders around the world. We hope it will inspire new collaborations and enable fundamental change in how the global economy is harnessed for social and environmental good.

Read the report: Rewiring the Economy: Ten tasks, ten years

Task 1: Measure the right things, set the right targets

Task 2: Use fiscal policy to correct externalities

Task 3: Drive socially useful innovation

Task 4: Ensure capital acts for the long term

Task 5: Price capital according to the true costs of business activities

Task 6: Innovate financial structures to better serve sustainable business

Task 7: Set a bold ambition, and innovate to deliver greater value

Task 8: Broaden the measurement and disclosure framework

Task 9: Grow the capability and incentives to act

Task 10: Harness communications for positive change

|

Rewiring-the-Economy-June-2016

'http://www.truevaluemetrics.org/DBpdfs/Sustainability/Cambridge/Rewiring-the-Economy-June-2016.pdf' | Open PDF ... Rewiring-the-Economy-June-2016 |

Task 1: Measure the right things, set the right targets

Governments can set bold targets for social and environmental progress, and adopt new measures to track how well the economy is delivering them.

Many policies are geared toward growing GDP without sufficient regard to the quality of the growth achieved. Such a limited strategy can be counterproductive in terms of meeting social and environmental goals. Governments should consider how well they are served by GDP, and whether their goals and strategies may have been distorted as a result of its ubiquitous application. New metrics that integrate changes in social and natural capital alongside economic output provide a more rounded view of economic progress.

Measurement is only one part of this story, the other being the targets that governments set on the basis of the metrics they agree. Clear, measurable commitments from governments are essential in areas such as binding carbon emissions targets, achieving or surpassing zero net waste, and rules and incentives to achieve zero net deforestation, integrated with goals relating to skills, employment and living standards.

Without clear targets, backed up by integrated measurements, legal mandates and political commitment, then other government actions – for example social and environmental policies – will continue to work against the grain of the economy rather than through it, producing mixed messages for business.

New metrics that integrate changes in social and natural capital alongside economic output provide a more rounded view of economic progress.

Task 2: Use fiscal policy to correct externalities

Governments can internalise environmental and social costs in economic activities through fiscal policy, benefitting sustainable business models.

Novel fiscal policies are required to ensure that the true costs of environmental and social externalities are borne by the economy rather than being offloaded on society. Examples of externalities include carbon emissions, various forms of pollution and waste, resource depletion, ecosystem loss and a wide range of social inequalities. This task could be tackled, for example, by differentially taxing business activities according to their environmental and social impacts – and rewarding positive performance. An example of this approach would be the use of revenues raised from carbon pricing to enable private financing of low carbon, climate resilient infrastructure.

Another powerful way to reflect and manage true costs is to remove or redirect subsidies that otherwise make unsustainable economic activity cheaper, for example in relation to fossil fuels, soil damage, biodiversity loss or the perpetuation of poverty. Governments should consider whether their current approach to subsidies may in fact be encouraging economic activities that run counter to sustainable development goals.

Are governments using fiscal policy to correct market failures that prevent business from delivering socially useful goods and services? Are governments setting a carbon price that reflects the full economic risks posed by climate change?

Governments should consider whether their current approach to subsidies may in fact be encouraging economic activities that run counter to sustainable development goals.

Task 3: Drive socially useful innovation

Governments can use every opportunity to create drivers and incentives for innovation aligned with core sustainability goals, and should exemplify and enable sustainable business.

There is a clear need for innovative approaches, technologies and systems to tackle the fundamental sustainability challenges facing the world. Government has a central role to play in driving and sustaining such innovation. There is no better way for governments to demonstrate their commitment to building a sustainable future than to use regulation, public spending and other policy instruments consistently to achieve this aim.

Public procurement, service delivery, planning policy, education, research funding, innovation support and other levers of industrial (and infrastructure) policy can all be harnessed to enhance 'public goods' such as living conditions, employment, public space and environmental quality. At a minimum, government activities should not be associated with undesirable outcomes such as low pay, excessive waste creation, or damage to important and vulnerable ecosystems, landscapes, communities and the climate. At best, government activities can be a powerful lever for change.

Are governments effective at driving innovation? Are they aligning efforts to drive and support innovation with their sustainability goals?

Are governments aligning efforts to drive and support innovation with their sustainability goals?

Task 4: Ensure capital acts for the long term

Investors of capital can demand more from their money, using their influence to drive long-term, socially useful value creation in the economy in the interests of their beneficiaries.

In broadening their expectations on capital, investors can reward companies for incorporating long-term risk and value creation in their business models. Expectations can be set and reinforced in numerous ways. These include the agreements established between different intermediaries in the financial value chain, shareholder votes on policies that do – or do not – align with long term value creation (such as remuneration and environmental performance), and the tools used to translate future business opportunities into present-day value.

Extending the timeframe over which financial risks and returns are modelled, and opening the analysis to key environmental, social and governance (ESG) risk factors, will build alignment between the way capital is deployed and the interests of its ultimate beneficiaries – the public.

This big and urgent reform faces an uphill climb against a well-known culture of short-termism in the finance sector, and warrants action from governments, regulators, capital owners, financial intermediaries, consultants, risk experts and business.

What would it take to incentivise the financial value chain to seek long-term performance?

Task 5: Price capital according to the true costs of business activities

Capital providers, and those who regulate them, can jointly consider how to reflect social and environmental risk factors in the cost of capital.

The cost of capital is a key factor in business decisionmaking. It is influenced by multiple drivers that interact with one another, including the business strategies of individual capital providers and the requirements set by regulators. Ultimately, the assessment of risk and return that underpins cost of capital calculations dictates how capital is deployed and hence which business activities are able to flourish.

Today, the cost of capital rarely reflects the true costs of business activities across equity, debt and insurance. This means that one of the key drivers of business decisionmaking is at best sending unhelpful signals to companies, and at worst allowing important risks to society to accumulate in the longer term. This danger is already being recognised by some central banks and financial regulators, who, for example, are asking whether the by-products of unsustainable economic activity, such as climate change and income inequality, could threaten financial stability.

Some individual capital providers are identifying strategies that enable them, on a unilateral basis, to reflect more closely the true costs of business activities in their cost of capital. For example, some banks require customers to meet certain environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards as a condition of business, while some investors integrate these considerations into their asset choices. These efforts need to be brought front and centre of financial institutions' thinking, enabled as necessary by fiscal, monetary and regulatory interventions.

Though they are regarded by some to be simply good risk management, how consistently are they being applied, and how visible is this to business?

The cost of capital rarely reflects the true costs of business activities across equity, debt and insurance.

Task 6: Innovate financial structures to better serve sustainable business

Financial intermediaries in particular can apply their influence and creativity to increasing the flow of capital into business models that serve society’s interests.

In recent decades financial intermediaries, such as banks, have demonstrated incredible creativity in extracting financial value from business and society, to the point where many stakeholders now regard them as an economy in their own right, serving their own purposes rather than the underlying needs of the 'real' economy that others inhabit.

It is critical that this same powerful instinct for innovation is now underpinned by social purpose. Business models that address society's essential needs are emerging all the time. In many instances, the companies that invent them struggle to access mainstream capital because the risks are perceived by financial intermediaries to be too high or the scale of their operation too small – take off-grid renewable energy in Africa. They find themselves reliant on government or donor capital, or turn to unconventional sources, which can make their growth more costly, slow or even not possible – yet they are almost certainly bright prospects for the future.

More work is required by institutions across the financial value chain, governments and businesses to understand how innovative financial services, including public-private financing structures, could be deployed to support and scale up sustainable business models. Patient capital, risk-sharing mechanisms, innovation support and capability building are all part of a rich picture of financial services that will fuel a new generation of businesses that contribute to global challenges such as poverty, inequality and climate change. It will also help the incumbents to grow in new, socially relevant, ways.

Could an improved understanding of this transition enable financial intermediaries to better support their clients?

Businesses that address society’s changing needs are almost certainly the brightest businesses of the future.

Task 7: Set a bold ambition, and innovate to deliver greater value

Businesses can seek models of value creation that generate a fair social contribution within the natural boundaries set by the planet.

We know that for many businesses, the current operating model isn’t going to be sustainable in the long term, and companies will have to transform their value-creation system. This will, for example, require sustainable production methods for agricultural commodities, circular manufacturing and consumption models, blends of product and service approaches, and a revolution in the energy system.

The shift business needs to make is dramatic and multiyear. It will be incredibly challenging for many companies, and unlikely to happen without clear aspirations and a strong imperative for change. For many companies it will mean working differently with partners and suppliers, and understanding the full lifecycle of their products and services. For incumbent players, this level of disruptive innovation is challenging, and is likely to lead to the rebalancing of corporate portfolios.

As is the case with governments, robust measures and targets, aligned with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), will be required to drive execution, alongside investment in strategy, R&D and corporate venture capital. Parallel innovation will be needed from the financial sector to provide capital, and from governments to set the right enabling conditions.

Companies will need to consider how value can be created while making a fair social contribution with neutral or positive impacts on the natural world. Is their strategy consistent with maintaining global temperature rise under 2°C, with a fair distribution of earnings between tax and profit? Do all staff and workers through the supply base receive at least a living wage?

Companies will need to consider how value can be created while making a fair social contribution with neutral or positive impacts on the natural world.

Task 8: Broaden the measurement and disclosure framework

Companies can build a fuller understanding of their impacts (and dependencies) on society, including the implications for capital allocation.

Business leaders say they must measure what they seek to manage. In recognition of this basic assumption, companies need to understand new facts about their business: the real rates at which the resources they use, such as water, soil, biodiversity and clean air, are being depleted; the actual risks their business is exposed to from market failures such as climate change; and the true impact of their operations on society. Companies can achieve this by adopting new standards for three major groups of decisions: financial accounting, management accounting and capital allocation.

By working with the accounting community to broaden the use of environmental, social and governance (ESG) reporting, companies can send a clear message to capital markets about their longer term approach to value creation. By accounting for natural capital, companies can develop a clearer appreciation of the true lifetime costs of their goods and services and make informed decisions about how to manage them. Finally, by building a true appreciation of the real costs of capital and lifetime risk profile of an investment, companies can enhance their capital allocation processes.

The transparency resulting from integrated reporting and disclosure by listed companies (as well as large private companies and public institutions) will facilitate a more informed dialogue with stakeholders about the role of business in meeting societal challenges.

What is the net contribution of a company, and how is it handling trade-offs?

Companies can send a clear message to capital markets about their longer term approach to value creation.

Task 9: Grow the capability and incentives to act

Companies can align their capital, talent and senior attention with a sustainable business vision, and ensure people are empowered to deliver.

In any fast-moving transition, the ability to learn and adapt is critical. In this case, companies can build their capability by educating and empowering individual leaders, organisations and wider industries to take a longer, broader view of value creation consistent with sustainable business success. This will involve purposefully reallocating capital, talent and senior attention from current models towards the allocation required to deliver on sustainable business ambitions.

Resource allocation is notoriously ‘sticky’ in most organisations, and there is evidence that active reallocators outperform the market. This is an important capability for organisations to build. Companies will benefit from increasing their human capital and developing the people and skills to operate in new ways that are consistent with sustainable business success.

Incentives matter and companies of all kinds – including in the financial sector – can review their reward and recognition schemes to ensure that managers are not facing perverse incentives to preserve the status quo, and are effectively rewarded for long-term, sustainable performance.

A simple test: is sustainability good for your career?

Companies will benefit from developing the people and skills to operate in new ways that are consistent with sustainable business success.

Task 10: Harness communications for positive change

Companies can use their communication and marketing muscle to build public understanding of (and appetite for) sustainable business.

A significant proportion of the information citizens and governments receive is via the communications, marketing and public relations undertaken by business. These powerful influences could be used to help stakeholders across civil society see why sustainable business makes sense, why a sustainable economy is not only critical for survival but a great place to live and do business. Our popular culture is based in large part on our relationships with brands. If those relationships could be harnessed for sustainability, then the shifts the world needs to make will be more likely to occur.

Marketing and communications professionals, as well as public affairs experts, have a vital role to play in building awareness and engaging in an informed debate about sustainability. Key starting points are customers, suppliers, investors, regulators, and the business schools that train the future employees of the firms concerned.

Given what is at stake for business in the transition to a sustainable economy, this is no time for greenwash. Not all stakeholders – including governments – are currently on board with the challenges, or pedalling hard to find solutions. Deploying corporate influence for positive policy and cultural change is an essential characteristic of a sustainable business. For example, how does a company show its investors that it is making capital work in the long term? And how is it communicating the need for effective enabling policies to governments?

Marketing and communications professionals, and public affairs experts, have a vital role in building awareness and engaging in an informed debate about sustainability.

Ten tasks for business, government and finance to lay the foundations for a sustainable economy

What the economy should be delivering: six broad social and environmental ambitions

Ten tasks for business, government and finance to lay the foundations for a sustainable economy

What the economy should be delivering: six broad social and environmental ambitions