Date: 2026-03-04 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00013036

Corporate Structure / Purpose

B Corps

Will Wall Street Embrace B Corps? ... Etsy, Laureate and Other B Corps Have an Opportunity to Bring Benefit Corporation Structure to the Public

Burgess COMMENTARY

Everything about corporate accountancy and financial reporting since the 19th century has been to protect investors against company operators that were trying to defraud them. This is still needed, but in recent decades there has been another essential need, that is, a way to account for and report on the impact of companies on society and the environment ... stakeholders as well as stockholders. There is progress towards this sort of reporting like GRI, IR, SASB et al, but they are very weak compared to conventional money accounting and financial reporting, and without strong impact accounting and reporting it will be a long time before impact investors get confidence to deploy their wealth into the impact benefit segment of the stock market. Legal frameworks help, but not much compared to strong numbers based on rigorous principled accounting, auditing and reporting.

Peter Burgess http://truevaluemetrics.org

Peter Burgess

Will Wall Street Embrace B Corps? ... Etsy, Laureate and Other B Corps Have an Opportunity to Bring Benefit Corporation Structure to the Public

Etsy set a new standard for ethical business, but after it went public, the markets struggled to figure out what it was worth. And, after Laureate announced an IPO in February, the first public B Corp that is also a benefit corporation was officially up for trading. How will the markets react?

Through its Etsy store, PlanetVintageEU of Tallinn, Estonia, sells photographs of custom messages made of caviar placed on mother-of-pearl. Photo by PlanetVintageEU.

Like many of the handmade crafts it sells, Etsy is unique. Of the nearly 6,000 publicly traded companies on the major U.S. stock exchanges, Etsy Inc. was, until recently, the only Certified B Corporation.

Laureate Education, the world’s biggest for-profit college company, became the second publicly traded B Corp when it made its initial public offering in February. And, now, Etsy’s future as a B Corp is in doubt. At stake is nothing less than the question of whether B Corps can be sold and succeed on Wall Street — and thus enter the mainstream of corporate America.

Can B Corps succeed on Wall Street and enter the mainstream of corporate America?

An online handmade and vintage goods marketplace based in Brooklyn, New York, Etsy finds itself at a crossroads. If it is to remain a B Corporation, its board of directors must decide whether to ask the shareholders to change the company’s corporate structure by August to become what is known as a “benefit corporation.” If the board declines to do so, Etsy will be stripped of its certification — and the fast-growing B Corp movement will lose one of its highest-profile adherents.

If this sounds confusing, well, it is. The confusion arises because B Corporations and benefit corporations are not the same thing. To become a B Corp, for-profit companies submit to a voluntary, third-party verification of their social and environmental impact, a process administered by the nonprofit B Lab. To become a benefit corporation, a company’s shareholders must approve the benefit-corporation legal structure, which requires the company to consider the interests of society and the environment when making decisions. (See B Corp vs. Benefit Corp chart for more specifics.)

If B Lab is to achieve its transformative vision — “that one day all companies compete not only to be the best in the world, but the best for the world” — then the big, publicly traded companies that dominate the U.S. economy need to become B Corps. Under present B Lab rules, those companies will need to become benefit corporations as well if they are incorporated in the District of Columbia or one of the 30 states that provide for them. Making that transformation, in turn, will require persuading Wall Street that legally binding commitments to serve workers, communities and the planet won’t come at the expense of shareholders.

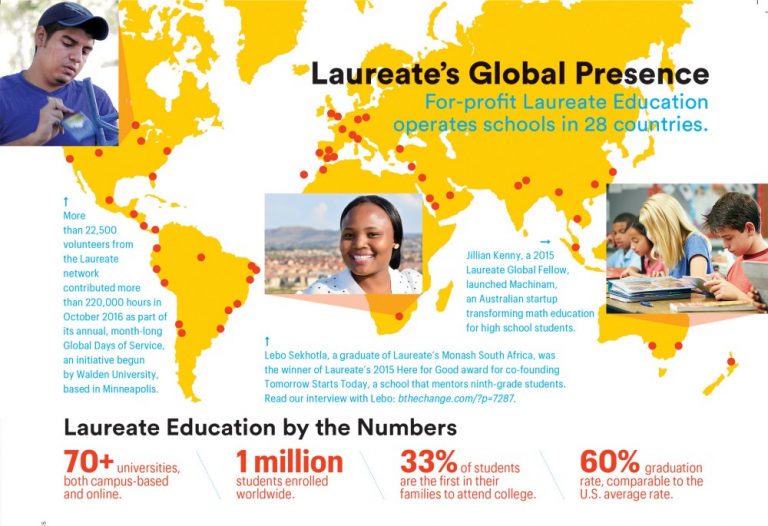

As one of the two publicly traded B Corps in the U.S., Etsy could continue to blaze a trail as a publicly traded benefit corporation. The company won’t disclose its plans. At the time of its IPO, Laureate, a global network of for-profit colleges (see map below), reported revenue of about $4.2 billion in 2015 and was both a B Corp and a benefit corporation. But, Laureate was facing challenges: The company was heavily in debt and dealing with a whistleblower complaint from a former executive.

Other large companies could help blaze the trail: One of nearly 2,000 privately held B Corps — the best-known include Patagonia, New Belgium Brewing and Warby Parker — could sell stock to the public. Or, a giant publicly traded company with one or more B Corp subsidiaries, such as Unilever, which had a 2015 revenue of $57.1 billion and owns Ben & Jerry’sand Seventh Generation, or Danone, which had a 2015 revenue of $24 billion and owns several B Corps, including Happy Family Brands, could choose to become B Corporations themselves.

It is mission-critical that U.S. public companies be able to join the B Corp movement.

“It is mission-critical that U.S. public companies be able to join,” says John Montgomery, a San Francisco-based corporate lawyer and leading advocate for the B Corp movement. Montgomery feels so strongly about the issue that he wrote to the board and senior management of Etsy, urging them to seize what he views as a historic opportunity, which has now been achieved by Laureate Education.

Montgomery wrote that the company that became the world’s first publicly traded benefit corporation would “have first-mover advantage as the immediate global standard-bearer of business as a force for good. … Be bold. Be the first. Make history. Reimagine commerce.”

What Will Wall Street Think?

Founded in 2005, Etsy was certified as a B Corp in 2012, went public in 2015 and was recertified last year. The Etsy website claimed 1.7 million active sellers and 27.1 million active buyers in January 2017, and listed gross merchandise sales of $2.39 billion in 2015. “We broke new ground with B Lab,” Chad Dickerson, Etsy CEO, wrote after recertifying. “We believe that all companies, no matter their size or what type of corporate structure they employ, can and should use the power of business to create social good.”

We believe that all companies, no matter their size or what type of corporate structure they employ, can and should use the power of business to create social good.

Kristina Salen, center left, Etsy’s chief financial officer, and Chad Dickerson, center right, chairman and CEO of Etsy, celebrate the company’s initial public offering on April 16, 2015. Photo by Mark Lennihan/Associated Press.

Investors, though, have reacted tepidly to Etsy. While its business has grown by double digits and the company closed its first day of trading on Nasdaq up 86 percent, its stock has since underperformed, leading Fortune to dub it “the worst-performing IPO of 2015.” It’s impossible to know whether Etsy’s B Corp status or some other factor — including the October 2015 launch of Amazon Handmade, a new competitor — has spooked investors since its IPO pop.

Becoming a benefit corporation could add another layer of uncertainty to Etsy shares. Last year, Dickerson told The Observer : “Right now, we don’t have plans to reincorporate as a public benefit corporation.” The CEO declined to speak with B Magazine, and Ariana Anthony, an Etsy spokeswoman, would not provide an update on its plans.

Globally, several publicly traded companies have become B Corps. They include Natura, a large cosmetics company based in Brazil, and Silver Chef, an equipment-financing firm serving the hospitality industry in Australia. Natura, traded on the São Paulo Stock Exchange with a 2015 revenue of 7.9 billion reals ($2.45 billion), amended its articles with approval from its institutional shareholders, including T. Rowe Price, Lazard and Oppenheimer, to include stakeholder commitments similar to those found in the benefit-corporation statute.

None is required to be a benefit corporation because the new corporate structure doesn’t exist in those countries yet. In 2015, Italy became the first country outside the U.S. to enact benefit-corporation legislation.

The B Corp Dilemma … or Opportunity

Changing corporate law was not what entrepreneurs and investors Jay Coen Gilbert, Bart Houlahan and Andrew Kassoy had in mind when they started B Lab a decade ago. The founders set out to develop a consumer-facing certification to spotlight companies that meet rigorous standards for performance and transparency. B Corp certification is often likened to fair-trade certification for coffee or USDA organic certification for food.

But the B Lab team soon heard from entrepreneurs, lawyers and experts, notably Marjorie Kelly, author of an influential book called The Divine Right of Capital, that many of the problems created by corporate America, such as wealth inequality and pollution, could be traced to corporate law. Conventional corporate structures, particularly the ubiquitous C corporation, require managers to operate solely in the interest of their owners, an idea known as “shareholder primacy.” The B Lab co-founders decided that needed to change, even though layering a legal requirement on top of the certification process would present an obstacle for some companies.

Marjorie Kelly, author of an influential book called The Divine Right of Capital, says that “many of the problems created by corporate America, such as wealth inequality and pollution, could be traced to corporate law.”

“It’s the single biggest impediment to the growth of the B Corp community,” Coen Gilbert says. But the movement needed “an underlying legal structure that makes it explicit that business has an expanded sense of citizenship” to its workers, the broader society and the planet.

The benefit-corporation structure puts the force of law behind the performance and transparency requirements of B Corp certification. B Corps that are incorporated in states that have passed benefit-corporation legislation must reincorporate within a specified period of time after the legislation is passed — four years in Delaware, where more than half of all U.S. public companies are registered. Delaware passed benefit-corporation legislation in August 2013, which is why Etsy and the other 80 or so Delaware B Corps must decide whether to adopt benefit-corporation status by August 2017.

Gov. Jack Markell met with more than a dozen CEOs and other business leaders in August 2013 to celebrate the creation of the first Public Benefit Corporations in Delaware. Photo by Mark Lennihan/Associated Press.

All 31 states with benefit-corporation laws require companies to support stakeholders, as well as shareholders, but the laws vary in their details. California’s law was among those that led the way. (See “California’s 3 Amigos,” below.)

In California, of the 43 B Corporations that faced a Jan. 1, 2016, deadline for becoming benefit corporations, 27 converted to benefit corporations, eight decertified because of the legal requirement, one had an exception because of regulatory issues, two have an extension and are continuing to work on the conversion, and five decertified for other reasons. Fair-trade clothier Indigenous Designs, organic yerba-mate beverage producer Guayakí, and book-publisher Berrett-Koehler — who had to get approval from about 200 shareholders — are among the California businesses that met the deadline.

More than 700 firms have become Delaware benefit corporations. Importantly, some of them, including AltSchool, Alter Eco, Kickstarter and Ripple Foods, are also B Corps and have raised outside capital from investors who understand that their shareholder interests are no longer paramount. “Major venture capitalists are investing,” says Jonathan Storper, a corporate lawyer who helped get California’s benefit-corporation law passed. But no one knows how the public markets will react to benefit corporations. Along with Etsy, Revolution Foods and Warby Parker must become benefit corporations by August or risk losing their B Corp status. Kirsten Tobey, co-founder of Revolution Foods, says the company hasn’t decided whether to make the switch.

“How will the public markets perceive a benefit corporation?” Tobey asks. “Right now, the answer to that question is purely speculative.”

B Lab and its executives have been trying to convince Wall Street that benefit corporations will deliver financial returns that match or exceed their peers’. “A lot of investors are on the way there,” says Rick Alexander, a corporate lawyer who is head of legal policy for B Lab.

Trillions of dollars are going into impact investing.

Larry Fink, chief executive at the world’s biggest investor, BlackRock, wrote a letter to CEOs at S&P 500 companies in early 2016, urging company leaders to shift to a long-term focus in their management for both the benefit of BlackRock’s clients and for the global economy.

Arguably, Etsy and the other B Corps would enhance their appeal to so-called impact investors by changing their status.

“Trillions of dollars are going into impact investing,” Montgomery says. He adds that without B Corp certification, which tracks and scores social and environmental performance, “it’s almost impossible [for investors] to tell who is greenwashing and who is real.”

In the meantime, multinational companies and large, public-market finance firms are working with B Lab, which has established a Multinationals & Public Markets Advisory Council, to see if the B Corp certification standards and legal requirements can work for big, publicly traded companies. Included on the council: Unilever, Danone and Campbell Soup Co., all of which have B Corp subsidiaries, and Morgan Stanley, Prudential and Generation Investment Management. The council’s recommendations are expected in late 2017.

B Lab is also partnering with a group of impact-oriented investors with the goal of having a group of small- to medium-sized public companies convert to benefit-corporation status by the end of the 2018 proxy season. Following the launch of this project last fall, B Lab and its partners have started outreach to select companies and have developed a letter of support for investor signatories.

Once you get an iconic company or two who adopts this form, it will spread like wildfire.

At a B Lab event last fall, Lorna Davis, a Danone executive, said the France-based food giant has a commitment to become a B Corp. Danone owns Happy Family Brands, a B Corp, and is acquiring WhiteWave Foods, whose brands include Horizon Organic, Silk and Earthbound Farms. Davis said: “We’re going to join the Danone North American business to the WhiteWave business in North America and become a public benefit corporation, which is very cool.”

B Lab isn’t counting on Etsy, Laureate, Danone or any other company to be the pioneer. The movement “will survive the departure of any one company,” says Coen Gilbert. He and his allies are sure that, before long, there will be plenty of publicly traded B Corps.

Montgomery says, “Once you get an iconic company or two who adopts this form, it will spread like wildfire.”

California’s 3 Amigos

Corporate lawyers are not typically activists. “We swear an oath to uphold the status quo,” jokes John Montgomery, a San Francisco attorney. But Montgomery, Jonathan Storper and Donald Simon — they called themselves “the three amigos” — were the driving force behind Assembly Bill 361, California’s landmark benefit-corporation law.

It wasn’t easy.

Left to right: Lawyers Donald Simon, John Montgomery and Jonathan Storper were the driving force behind the passage of California’s landmark benefit-corporation legislation in 2012. Photo by John Montgomery.

In 2008, Storper had drafted a benefit-corp-predecessor bill. It was swiftly ratified by the California State legislature, only to be vetoed by then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. Conservative business groups warned that the law might impose social or environmental obligations on all companies, even though it does not. “People are threatened by change,” Storper says.

In 2011, the B Lab co-founders enlisted Montgomery, Storper and Simon, working pro bono, to take another shot. Only one state, Maryland, had a benefit-corporation law. If California and New York could be persuaded to pass the legislation, Delaware, where most U.S. public companies are registered, would come under pressure to follow suit.

The three amigos all had worked in the world of values-driven business. Storper’s firm, Hanson Bridgett, was the first law firm to become a B Corp. He organized a series of forums on sustainability, where he met B Lab co-founder Jay Coen Gilbert. Montgomery worked with Silicon Valley entrepreneurs whose idealism he admired. “Part of what I’m about,” he says, “is helping leaders lead from the heart.”

The debate heated up. “We were David and the flexible-purpose people were Goliath.

Simon co-founded the U.S. Green Building Council’s Northern California Chapter and Build It Green, two organizations that helped make California a global mecca for sustainable-building practices. “I’m a tree-hugger who went to law school,” he says.

But they had little experience lobbying. And the legislative process they spearheaded was muddied by a proposal to create yet another corporate form, called the “flexible-purpose corporation,” which also was designed to give companies the freedom to pursue socially responsible activities. It was put forth by lawyers from big firms who were active in the California Bar Association.

The debate heated up. “We were David and the flexible-purpose people were Goliath,” Montgomery says.

Storper says: “I was persona non grata among some corporate lawyers in California.” The benefit corporation advocates felt the flexible-purpose bill could be used as a greenwashing tool by big companies like Chevron, which could get the designation by, they say, building a few playgrounds.

The lawyers pushing flexible-purpose legislation viewed the benefit-corporation advocates as interlopers. Susan Mac Cormac, a partner at Morrison & Foerster who supported the flexible-purpose bill, thought the early drafts of the benefit-corporation bill were sloppy. The flexible-purpose form, she says, was designed to improve the performance of big public companies, however imperfect.

“I don’t want to let big companies off the hook,” she says.

In the end, California lawmakers passed both the benefit-corporation bill and a bill establishing flexible-purpose corporations, which are now known as Social Purpose Corporations.

In the end, California lawmakers passed both the benefit-corporation bill and a bill establishing flexible-purpose corporations, which are now known as Social Purpose Corporations. Gov. Jerry Brown signed both into law. On the day the benefit-corporation law took effect in 2012, Patagonia, led by its founder Yvon Chouinard, became the first company to register as a California benefit corporation.

At the time, Chouinard declared, “I hope five or 10 years from now, we’ll look back on this day and say this was the start of a revolution, because the existing paradigm isn’t working anymore. This is the future.”

Note: B Lab and John Montgomery are shareholders in B the Change Media.

This article was originally published in the Spring 2017 issue of B Magazine and can be found here online

_____________________

Marc Gunther is a veteran journalist, speaker, and writer who reported on business and sustainability for many years. Since March 2015, he has been writing about foundations, nonprofits and global development on his blog, Nonprofit Chronicles.