Date: 2026-01-18 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00011246

People

Fela Kuta

The art provocateur Fela Kuti who used sex and politics to confront

Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

The art provocateur Fela Kuti who used sex and politics to confront

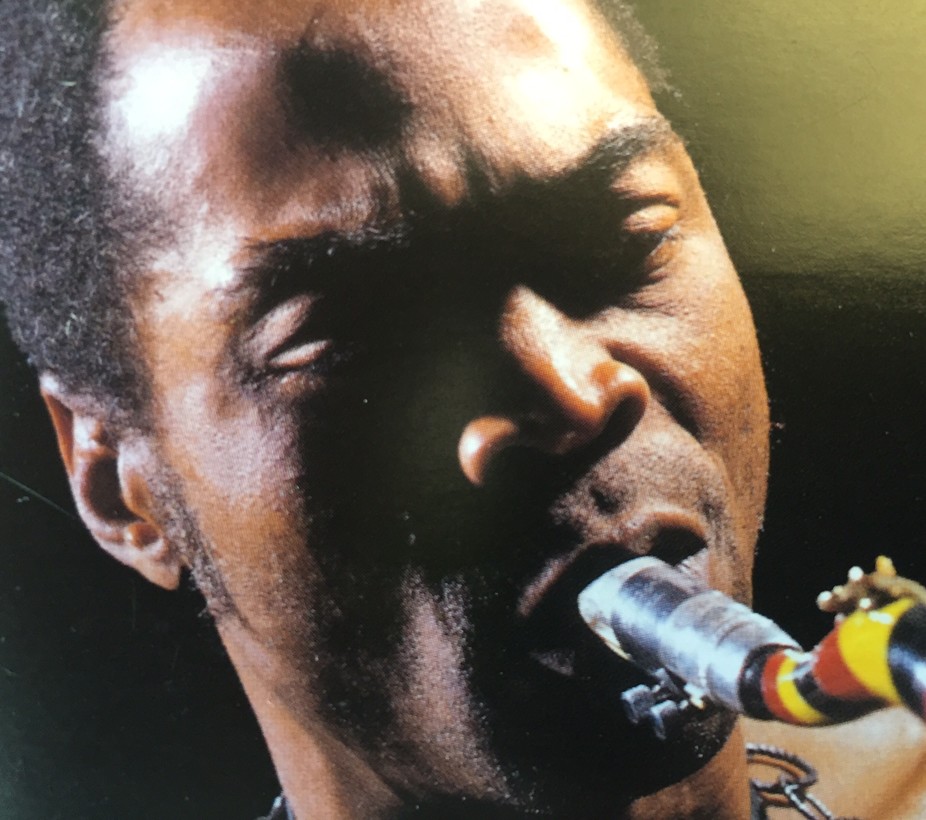

Fela Kuti - from the cover of his album ‘Teacher Don’t Teach Me Nonsense’

Olufela Olusegun Oludotun Ransome-Kuti would have been 78 this year. It is well within the realm of possibility that he would still be alive if not for the maltreatment meted out by the Nigerian state and the lack of standard antiretroviral therapy.

So, considering the delights of possibility, let us assume Fela is still alive, making music. I can only imagine what the music would be like by now – not to mention the generations of musicians who would have emerged out of the freedom and inspiration of the Shrine, Fela’s music venue in Lagos. By now Fela would be the elder statesman of the African music world, with awards and accolades galore. As it is, we have his music and the memories. Maybe that is all we need.

It is helpful for me to start by addressing ideas of art as confrontation, the very nature of an art that is praised and vilified, depending on the political and social state of a community and its people. That art is confrontational is not an assumption of the overtly political in art. It is much more than that.

Na Poi and Mattress, two well-known early songs by Fela, were clear and deliberate confrontations in their own time. Open and Close was equally disturbing in due course. There is always something in the denied pleasure of the salacious; Fela was aware of this and made it apparent.

The title track from Fela’s album ‘Open and Close’.

Sex in the songs

Sex was everywhere, from clothing, to language, to dancing. The birth rate in the country attested to the familiar nature of what Fela was singing about. But mentioning it – that was something else, let alone singing about it publicly. This transparency soon became an affront.

It is eminently appropriate to blame the government for the use of the state apparatus against one of its eminent citizens. But the population at large, having to deal with the realities Fela confronted them with, engendered collusion with the violence meted out to him.

In 1986, in an essay titled “Fela Anikulapo-Kuti: The Art of an Afrobeat Rebel”, Randall F Grass wrote:

Fela has spent more than 15 years making an artistic statement by breaking down the barriers between his artistic performance and his private life. He has obliterated the notion of ‘performance’ as something existing separate from life. He extends a traditional African concept of art – especially music – as being an integral component of both ordinary and extraordinary human activity. Typically, though, he turned such traditions upside-down even as he affirmed them; this is one reason why Fela Anikulapo-Kuti remains Africa’s most challenging and charismatic popular music performer.

This turning upside-down of a system is one of the hallmarks of a decent artistic practice – when the artist is thought to seek art for no more than self-aggrandisement. But this was a case where the artist was seeking authenticity. Fela did not want to upset music as a practice, he wanted to save popular music from remaining simply a hagiographic exercise. And he succeeded.

Fela the teacher

Contemporary African music has taken more from Fela’s practice than from that of his ascendants and contemporaries. This is because he offered new direction, self-awareness and confident assurance that the artist has to be free. The anachronism inherent in popular music is that it leans too much on tradition. With Fela it was important to see that it was possible to break this stifling mould of convention and survive as an artist.

For Fela, there was the Shrine, the venue that he made for himself so that he would be able to devote himself to his music. It provided him with the security to develop his ideas to the point where he could experiment with ease.

Fela worshipping at his venue, the Shrine.

By contemporary accounts, his then new style of music, Afrobeat, was hard to accept by those who heard it when it was new. But time and the freedom to experiment meant he could continue with the musical innovations he believed in. This cloistered environment, with a committed and sympathetic cohort of early adopters, meant Fela’s music could flourish.

It is evident that the people who made their way and their pilgrimages to Shrine knew there were involved in something particular and significant. Why else would they ignore the derision, potential loss of reputation, and “advice” not to go there from state authorities?

This feedback loop – Fela to fans: fans to Fela – is one of the reasons why his music could emerge on its own terms. Unlike his contemporaries exercising their musical prowess in front of a crowd who had invited and paid for them to come and entertain the rich and powerful, Fela’s fans had travelled to see him and had paid to be educated.

The self-imposed isolation of the Shrine bore considerable fruit. Fela was able to define his music on his own terms. This is what artists now need.

The Black President

Fela is not known for holding back on his opinion, and I write in the present tense, to point to the continuous relevance of the man who came to be known as the “Black President”.

This accolade is something particular. It is not national, or even continental, but it represents a sizeable portion of the world’s population. The title of Black President is not accidental – it relates to the project Fela took on himself and that he was soon embraced for.

Fela seemed to instinctively understand the role of the artist as provocateur, the one to see what it takes to change the way things are to the way he imagines they ought to be. The good thing is that time has shown that he was right on most things.

Fela demanded that people focus on their experiences as people, making their lives important. He did this with humour, for example in his song Stalemate.

The title track from Fela’s album ‘Stalemate’.

The ease of placing sexual politics, economics and mores in deep tension is telling. If the men in “Stalemate” did not feel obliged to buy the “fine lady” a drink in the first place, there would be no story. The ability to pull all of this together is what makes Fela so illuminating to visual artists.

Fela collects the feeling of the people and gives it back as concentrate. He goes from being the “Boogie Man” of a generation of parents, to the focus of a government determined to stamp out the voice that spoke on behalf of the people – doing the job of the artist.

Teacher Don’t Teach Me Nonsense

Close inspection of their world is one of the things artists are supposed to do. While it tends to expose society’s underbelly – the things that would otherwise remain hidden – it does so at its own expense.

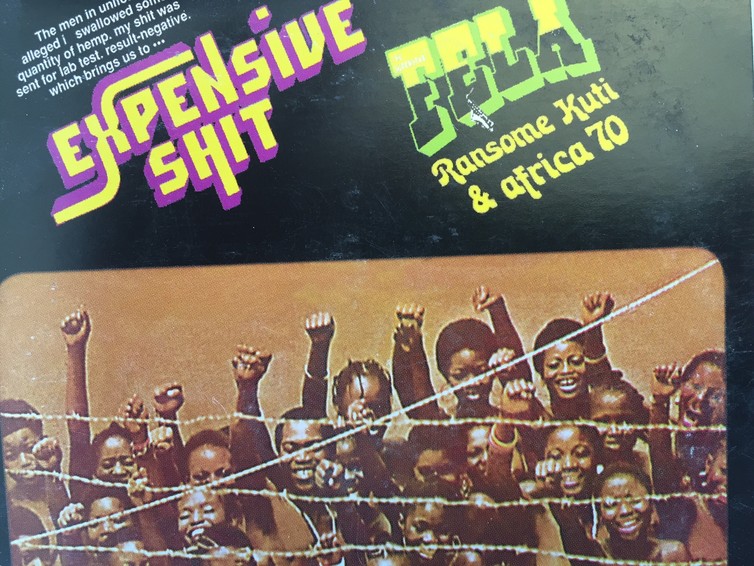

Shuffering and Shmiling was quite the hit when I was growing up. It came hot on the heels of Yellow Fever and Zombie. It sadly came long before, it seems, the mournful Coffin for Head of State became necessary and the scatological Unknown Soldier (Part 1 and 2) became inevitable. Keeping the tone balanced, the release of “Expensive Shit” should be no surprise in retrospect. It is the descriptive material of choice in the face of apparent irrationality:

Make you no go anywhere/ Just wait there make I tell you something/

[Chorus] Fela, you don come again!

I never come again/ I still live faraway/ Make you wait till I reach where I dey go

The cover of Fela’s album ‘Expensive Shit’.

Being an artist of any kind requires independence and perseverance. Fela Anikulapo-Kuti has come to epitomise the determination and single-mindedness of the artist for me. There is obvious value in toeing the line – politically, culturally, socially and even financially – and being reminded ad nauseam that there will always be the pragmatics of remaining an artist. Yet, the reality of being an artist demands that choices will be made that fly in the face of reason. It is the ability to embrace the irrational that makes the artist viable.

If it were a simple revolution, as if revolutions are simple, one might be able to dismiss Fela’s activities as crowd-pleasing, attention-seeking moves. But the continuing reverberations of his work tell another story. They point to the man who saw his world change, from colonial state, to postcolonial state, to rentier state, and did not live to see the emergence of continued democracy. What he did foresee was its coming, and he did all he could to usher in its coming.

Nigerians file past Fela’s body in Lagos on August 11, 1997. Reuters

I think Fela would be proud of his many descendants. But then we know Fela – the Anikulapo in his double-barrel surname means “I have death in my pouch” – is not dead, that he watches, for the man that holds death in a pouch does not knowingly let death out.

Author Raimi Gbadamosi Professor of Fine Arts, University of Pretoria

Disclosure statement Raimi Gbadamosi does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Partners

University of Pretoria University of Pretoria provides funding as a partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

The Conversation’s partners View partners of The Conversation

Republish this article We believe in the free flow of information. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence, so you can republish our articles for free, online or in print.