Date: 2026-03-07 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00004659

Initiatives

Collective Impact

Embracing Emergence: How Collective Impact Addresses Complexity

Burgess COMMENTARY

Collective Impact seems to be a formalization of The Burgess Method (TBM) that I used successfully in my own work in development planning and project design. What I advocated was not taken up in large part because the international devalopment process is structured around a set of development institutions that are organized along sector lines. TBM was a way to make the priority needs of a community, the priority of external development initiatives with no single sector in a dominant position. TBM was based on the planning model that we used successful in the corporate environment.

Peter Burgess

Embracing Emergence: How Collective Impact Addresses Complexity

Collective impact is upending conventional wisdom on how we achieve social progress.

Organizations around the world have begun to see collective impact as a new and more effective process for social change. They have grasped the difference our past articles emphasized between the isolated impact of working for change through a single organization versus a highly structured cross-sector coalition.1 Yet, even as practitioners work toward the five conditions of collective impact we described earlier, many participants are becoming frustrated in their efforts to move the needle on their chosen issues. (See “The Five Conditions of Collective Impact,” below.)

Collective impact poses many challenges, of course: the difficulty of bringing together people who have never collaborated before, the competition and mistrust among funders and grantees, the struggle of agreeing on shared metrics, the risk of multiple self-anointed backbone organizations, and the perennial obstacles of local politics. We believe, however, that the greatest obstacle to success is that practitioners embark on the collective impact process expecting the wrong kind of solutions.

The solutions we have come to expect in the social sector often involve discrete programs that address a social problem through a carefully worked out theory of change, relying on incremental resources from funders, and ideally supported by an evaluation that attributes to the program the impact achieved. Once proven, these solutions can scale up by spreading to other organizations. The problem is that such predetermined solutions rarely work under conditions of complexity—conditions that apply to most major social problems—when the unpredictable interactions of multiple players determine the outcomes. And even when successful interventions are found, adoption spreads very gradually, if it spreads at all.

Collective impact works differently. The process and results of collective impact are emergent rather than predetermined, the necessary resources and innovations often already exist but have not yet been recognized, learning is continuous, and adoption happens simultaneously among many different organizations.

In other words, collective impact is not merely a new process that supports the same social sector solutions but an entirely different model of social progress. The power of collective impact lies in the heightened vigilance that comes from multiple organizations looking for resources and innovations through the same lens, the rapid learning that comes from continuous feedback loops, and the immediacy of action that comes from a unified and simultaneous response among all participants.

Under conditions of complexity, predetermined solutions can neither be reliably ascertained nor implemented. Instead, the rules of interaction that govern collective impact lead to changes in individual and organizational behavior that create an ongoing progression of alignment, discovery, learning, and emergence. In many instances, this progression greatly accelerates social change without requiring breakthrough innovations or vastly increased funding. Previously unnoticed solutions and resources from inside or outside the community are identified and adopted. Existing organizations find new ways of working together that produce better outcomes.

Leaders of successful collective impact initiatives have come to recognize and accept this continual unfolding of newly identified opportunities for greater impact, along with the setbacks that inevitably accompany any process of trial and error, as the powerful but unpredictable way that collective impact works. They have embraced a new way of seeing, learning, and doing that marries emergent solutions with intentional outcomes.

Complexity and Emergence

It would be hard to deny that most large-scale social problems are complex. Issues such as poverty, health, education, and the environment, to name just a few, involve many different interdependent actors and factors. There is no single solution to these problems, and even if a solution were known, no one individual or organization is in a position to compel all the players involved to adopt it. Important variables that influence the outcome are not and often cannot be known or predicted in advance.2 Under these conditions of complexity, predetermined solutions rarely succeed.

Leaders of succesful collective impact initiatives have embraced a new way of seeing, learning, and doing that marries emergent solutions with intentional outcomes.

Predetermined solutions work best when technical expertise is required, the consequences of actions are predictable, the material factors are known in advance, and a central authority is in a position to ensure that all necessary actions are taken by the appropriate parties. Administering the right medicine to a patient, for example, generally gives predetermined results: the medicine has been proven to work, the benefits are predictable, the disease is well understood, and the doctor can administer the treatment. Much of the work of the nonprofit and public sectors is driven by the attempt to identify such predetermined solutions. In part, this is due to the expectations of funders and legislators who understandably want to know what their money will buy and predict how the discrete projects they fund will lead to the impacts they seek.

Unlike curing a patient, problems such as reforming the US health care system cannot be accomplished through predetermined solutions. No proven solution exists, the consequences of actions are unpredictable, and many variables—such as the outcome of elections—cannot be known in advance. Furthermore, any solution requires the participation of countless government, private sector, and nonprofit organizations, as well as a multitude of individual citizens. In these circumstances, emergent solutions will be more likely to succeed than predetermined ones.

Taken from the field of complexity science, “emergence” is a term that is used to describe events that are unpredictable, which seem to result from the interactions between elements, and which no one organization or individual can control. The process of evolution exemplifies emergence. As one animal successfully adapts to its environment, others mutate in ways that overcome the advantages the first animal has developed. There is no ultimate “solution” beyond the process of continual adaptation within an ever-changing environment.

To say that a solution is emergent, however, is not to abandon all plans and structures.3 Rather than deriving outcomes by rigid adherence to preconceived strategies, a key tenet of addressing complex problems is to focus on creating effective rules for interaction. These rules ensure alignment among participants that increases the likelihood of emergent solutions leading to the intended goal. Consider, for example, how flocks of birds are able to demonstrate such amazing coordination and alignment, with thousands of independent bodies that move as one, reacting together in nanoseconds to changes in geography, topography, wind currents, and potential predators.4 Scientists have discovered that just three simple rules govern their interaction: maintain a minimum distance from your neighbor; fly at the same speed as your neighbor; and always turn towards the center. All three rules are essential for flocking. When they are in place, it is as if all birds collectively “see” what each bird sees and “respond” as each bird responds.5

The five conditions for collective impact similarly serve as rules for interaction that lead to synchronized and emergent results. A common agenda, if authentic, creates intentionality and enables all participating organizations to “see” solutions and resources through similar eyes. Shared measurement, mutually reinforcing activities, and continuous communication enable participants to learn and react consistently with the common agenda to emerging problems and opportunities. Meanwhile, the backbone organization supports fidelity by the various cross-sector players to both the common agenda and rules for interaction.

When properly put into motion, the process of collective impact generates emergent solutions toward the intended outcomes under continually changing circumstances. As with evolution, this process is itself the solution. And, as with a flock of birds, effective collective impact efforts experience a heightened level of vigilance that enables participants to collectively see and respond to opportunities that would otherwise have been missed.

Collective Vigilance

It is commonplace to bemoan the insufficiency of resources and solutions needed to address the world’s most challenging problems. As successful collective impact efforts around the world are discovering, however, the problem is not necessarily a lack of resources and solutions, but our inability to accurately see the resources and solutions that best fit our situation.

When each organization views the availability of resources and the range of solutions through the lens of its own particular agenda, the resulting kaleidoscope conceals many opportunities. Collective impact efforts, however, sharpen a community’s collective vision. Having a shared understanding of the problem and an appropriately framed common agenda increases the likelihood that communities will see relevant opportunities as they emerge. The novelty of working with people from different sectors brings a fresh perspective that encourages creativity and intensifies effort. This, in turn, can motivate more generous support from both participants and outsiders. The rules for interaction from collective impact create an alignment within complex relationships and sets of activities which, when combined with shared intentionality, causes previously invisible solutions and resources to emerge.

In 2008, for example, the city of Memphis, Tenn., and Shelby County initiated a multi-pronged collective impact initiative called Memphis Fast Forward that includes a focus on improving public safety called Operation: Safe Community. After three years, cross-sector stakeholders looked at data regarding progress in public safety and concluded they were making good headway on two of three priority thrusts: policing and prosecution. Unfortunately, they saw little progress in the third area of violence prevention. The parties agreed to double down their efforts and re-tool the plan for prevention. Three months later, the U.S. Department of Justice announced the formation of the National Forum on Youth Violence Prevention, with federal support available to communities aspiring to higher levels of performance in prevention activities. Memphis Fast Forward quickly jumped into action and, three months later, was one of six communities nationwide to be selected for funding.

The leaders of Memphis Fast Forward could not have anticipated and planned for the new resources that came from the Department of Justice. Had the participating organizations been acting in isolation, they most likely would not have been aware of the new program, and even if one or two solitary nonprofits knew of the potential funding, it is unlikely that they could have mobilized a sufficient community-wide effort in time to win the grant. Collective impact enabled them to see and obtain existing resources that they otherwise would have missed.

The vigilance inspired by collective impact can lead to emergent solutions as well as resources. In 2003, stakeholders in Franklin County, a rural county in western Massachusetts, initiated an effort called Communities that Care that focused on reducing teen substance abuse by 50 percent. A key goal in the common agenda was to improve the attitudes and practices of families. The initial plan was to “train the trainers” by working with a cadre of parents to learn and then teach other parents. Unfortunately, in 2006 and 2009, the data showed no improvement in parental behaviors. The initiative then decided to try something new: a public will-building campaign designed to reach all parents of 7th through 12th grade students. The initiative worked with schools to send postcards home, and with businesses to get messages on pizza boxes, grocery bags, paper napkins, in fortune cookies, in windows, on banners, on billboards, and on the radio. The initiative had also come across an outside research study showing that children who have regular family dinners are at lower risk for substance use, so they included that message as well.

Leaders of the effort were paying close attention to the campaign to determine which messages had any impact. Through surveys and focus groups the initiative discovered that the family dinner message resonated strongly with local parents, in part because it built on momentum from the local food movement, the childhood anti-obesity movement, and even the poor economy that encouraged families to save money by eating at home. Armed with this evidence, the initiative went further, capitalizing on national Family Day to get free materials and press coverage to promote the family dinner message. As a result, the percentage of youth having dinner with their families increased 11 percent and, for the first time since the effort was initiated seven years earlier, Franklin County saw significant improvements in key parental risk factors.6

The Franklin County example demonstrates how collective impact marries the power of intentionality with the unpredictability of emergence in a way that enables communities to identify and capitalize on impactful new solutions. In this case, the failure to make progress against an intended goal prompted both a new strategy (switching from parental train-the-trainer groups to a public awareness campaign) and a search outside the community for new evidence based practices (family dinners) that supported their goal of reducing parental risk factors. This clarity of vision also enabled the initiative to capitalize on unrelated and unanticipated trends in food, obesity, and the economy that emerged during the course of the work and amplified their message.

In both of these examples, the ongoing vigilance of multiple organizations with a shared intention, operating under the rules for interaction of the collective impact structure, empowered all stakeholders together—flexibly and quickly—to see and act on emerging opportunities. The intentions never changed, but the plans did. And in both cases, the resources and solutions that proved most helpful might have been overlooked as irrelevant had the stakeholders adhered to their original plans.

It may seem that these two examples were just “lucky” in coming upon the resources and solutions they needed. But we have seen many such collective impact efforts in which the consistent unfolding of unforeseen opportunities is precisely what drives social impact. This is the solution that collective impact offers.

Collective Learning

The leaders of both the Memphis and Franklin County collective impact initiatives learned that they were not making progress on one dimension of their strategies. Of course, nonprofits and funders learn that they have unsuccessful strategies all the time. What was different in these cases is that the rules for interaction established by collective impact created a continuous feedback loop that led to the collective identification and adoption of new resources and solutions.

Continuous feedback depends on a vision of evaluation that is fundamentally different than the episodic evaluation that is the norm today in the nonprofit sector. Episodic evaluation is usually retrospective and intended to assess the impact of a discrete initiative. One alternative approach is known as “developmental evaluation,”7 and it is particularly well suited to dealing with complexity and emergence.8

Developmental evaluation focuses on the relationships between people and organizations over time, and the problems or solutions that arise from those relationships. Rather than render definitive judgments of success or failure, the goal of developmental evaluation is to provide an on-going feedback loop for decision making by uncovering newly changing relationships and conditions that affect potential solutions and resources. This often requires reports on a weekly or biweekly basis compared to the more usual annual or semi-annual evaluation timeline.

The Vibrant Communities poverty reduction initiative in Canada has successfully employed developmental evaluation within their collective impact efforts to help identify emergent solutions and resources. Facilitated by the Tamarack Institute, which serves as a national backbone to this multi-community effort, Vibrant Communities began 11 years ago with a traditional approach to accounting for results based on developing a logic model and predetermined theory of change against which they would measure progress. They quickly discovered that very few groups could develop an authentic and robust theory of change in a reasonable period of time. Often the logic model became an empty exercise that did not fully reflect the complex interactions underlying change. Tamarack then shifted to a more flexible model that embodied the principles of developmental evaluation. They began to revise their goals and strategies continuously in response to an ongoing analysis of the changes in key indicators of progress, as well as changes in the broader environment, the systems of interaction, and the capacities of participants. Although it sounds complicated, such a process can be surprisingly straightforward. The Vibrant Communities initiative in Hamilton, Ontario, for example, developed a simple two-page weekly “outcomes diary” to track changes in impact on individuals, working relationships within the community, and system level policy changes.

Vibrant Communities’ rapid feedback loops and openness to unanticipated changes that would have fallen outside a predetermined logic model enabled them to identify patterns as they emerged, pinpointing new sources of energy and opportunity that helped to generate quick wins and build greater momentum. This approach has provided critical insights—for individual communities and the initiative as a whole—into how interlocking strategies and systems combine to advance or impede progress against a problem as complex as poverty reduction.

We have earlier emphasized the importance of shared measurement systems in collective impact efforts, and they are indeed essential for marking milestones of progress over time. Because most shared measurement systems focus primarily on tracking longitudinal quantitative indicators of success, however, the systems are not typically designed to capture emergent dynamics within the collective impact effort—dynamics which are multi-dimensional and change in real time. As a result, developmental evaluation can provide an important complement to the “what” of shared measurement systems by providing the critical “how” and “why.”

In its Postsecondary Success (PSS) program area, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is also using developmental evaluation to better understand emergent opportunities in the context of complexity. While the PSS is not fully engaging in collective impact, its Communities Learning in Partnership (CLIP) is instilled with the same spirit and many of the requisite conditions for collective impact. The initiative engages diverse stakeholders, including the K–12 educational system, higher education, the business community, political, civic, and community leaders, and social service providers with the goal of increasing post-secondary completion rates among low-income young adults. The general framework for change for the CLIP work provides guideposts, but is not overly prescriptive. In seeking to improve post-secondary completion rates among low-income youth, grantee communities have been asked to focus on four broad-based levers for change: developing partnerships, using data to inform their strategies, building commitment among stakeholders, and tackling policy and practice change. Yet it is entirely up to the communities, armed with deep knowledge about their local context, to make sense of these four levers and to identify and pursue emergent opportunities for themselves.

The Gates Foundation has retained the OMG Center to perform developmental evaluation to gain greater insight into emerging solutions and to understand what it takes for a community to coalesce around a postsecondary completion goal. This requires near-constant contact. The OMG evaluation team speaks with the technical assistance providers and the foundation program officer every two weeks and reviews documents and data from the grantee sites on a rolling basis. In most cases, OMG has ready access to document sharing websites that grantees have set up to support the partnership. OMG structures interviews to build off of previous conversations and produces a running narrative that documents in detail how the work is unfolding. OMG also connects directly with the grantees and their partners through interviews and site visits every three to four months.

Following every major data collection point, OMG shares a rapid feedback memo with the site, the technical assistants, and the foundation team containing their observations and questions for consideration. OMG shares new analysis and insights nearly every eight weeks, and pairs ongoing assessments with a debriefing call or a reflection meeting. They also hold an annual meeting to review the program’s theory of change, enabling the evaluation, foundation, and technical assistance partners to revise it as emergent opportunities are identified. This developmental evaluation has allowed the Gates Foundation, OMG, and grantee communities to capture and synthesize an unprecedented level of nuance about how change happens in a particular community—who needs to drive the agenda, who needs to support it, how they can get on board, and what structures are needed to support the effort. The developmental evaluation has also helped unearth the habitual and cultural practices and beliefs that exert enormous influence on how important organizations and leaders—such as school districts, higher education institutions, and municipal leaders—operate. These informal systems could have been easily overlooked in a more traditional formative evaluation with a more structured framework of analysis.9 As vigilant as participating members of a collective impact initiative may be, efforts to identify improvements can be helped by a “second set of eyes” focused on identifying emergent patterns. In the case of CLIP, the added vision afforded through developmental evaluation resulted in significantly improved learning around opportunities and resources, leading to important changes in the actions of key stakeholders.

Collective Action

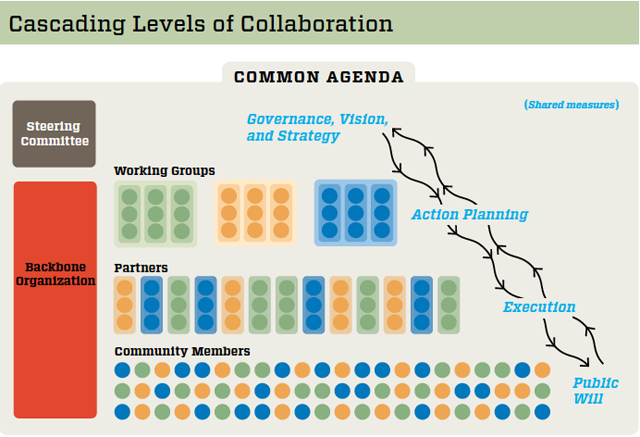

Capturing learnings is one thing, acting on them is another. The traditional model of social change assumes that each organization learns its own lessons and finds its own solutions which are then diffused over time throughout the sector. In effective collective impact initiatives, however, learning happens nearly simultaneously among all relevant stakeholders and, as a result, many organizations develop and respond to new knowledge at the same time. This has two important consequences: first, new solutions are discovered that bridge the needs of multiple organizations or are only feasible when organizations work together, and second, all participating organizations adopt the new solution at the same time. We described the key to this coordinated response in our previous article, “Channeling Change: Making Collective Impact Work,” published in Stanford Social Innovation Review in January 2012, as “cascading levels of linked collaboration.” This structure is currently being used in the majority of effective collective impact efforts we have researched. (See “Cascading Levels of Collaboration,” below.)

When supported by an effective backbone and shared measurement system, the cascading levels of collaboration creates a high degree of transparency among all organizations and levels involved in the work. As the illustration suggests, information flows both from the top down and from the bottom up. Vision and oversight are centralized through a steering committee, but also decentralized through multiple working groups that focus on different levers for change.

Our research indicates that these working groups are most successful when they constitute a representative sample of the stakeholders. This leads to emergent and anticipatory problem solving that is rigorous and disciplined and, at the same time, flexible and organic. Structuring efforts in this way also increases the odds that a collective impact initiative will find emergent solutions that simultaneously meet the needs of all relevant constituents, resulting in a much more effective feedback loop that enables different organizations to respond in a coordinated and immediate way to new information. Similar to the birds in a flock, all organizations are better able to learn what each organization learns, enabling a more aligned, immediate, and coordinated response. Consider Tackling Youth Substance Abuse (TYSA), a teen substance abuse prevention initiative in Staten Island, New York. The overall goal of this collective impact effort, launched in May of 2011, is to decrease youth prescription drug and alcohol abuse in Staten Island, a community of nearly 500,000 people. The effort is coordinated through a steering committee and one-person backbone organization. There are four working groups: a social norms group focused on changing attitudes and behaviors of youth and parents, a retail and marketplace availability group focused on policies that limit inappropriate purchasing of prescription drugs and alcohol, a continuum of care group focused on developing and coordinating high quality approaches to screening-referral-treatment-and-recovery, and a policy and advocacy group focused on creating a policy platform regarding facets of teen substance abuse.

Stakeholders in the continuum of care working group include representatives from those who treat youth substance abuse disorders (such as hospitals, and mental health and substance abuse providers), those who work with youth who might have or be at significant risk of developing a substance abuse disorder (such as the New York City Department of Probation and drug treatment court), those who work on health protocols (such as the Department of Health) and those who provide counsel to youth (such as the YMCA and Department of Education substance abuse prevention counselors). A key finding emerging from this group’s initial stages of work was that, among treatment providers on Staten Island, there was no consistent screening tool for substance abuse disorders. Further investigation yielded the fact that a number of organizations working with youth at significant risk of developing a substance abuse disorder, such as probation, did not use a screening tool at all. Remarkably, pediatricians were also among the population of providers who had no consistent protocol for substance abuse screening and referral.

This led the continuum of care workgroup to identify an evidence-based screening tool approved by the local and state health agencies that quickly assesses the severity of adolescent substance use and identifies the appropriate level of treatment. The workgroup felt that this tool, called the CRAFFT, if used on Staten Island more widely, would lead to more system wide early intervention and referrals for assessments and treatment services for youth with substance use disorders, as well as those at risk of developing disorders.

At the same time, the social norms group was looking for a way that coaches, parents, and other people who came in contact with youth outside of formalized systems could better assess substance abuse. Through the cascading collaborative structure, the backbone organization and steering committee had a window into the activity of all work groups, enabling each of them to understand the needs of the others. Although there was a universal need to improve screening and referral, the diverse populations required different approaches. Specifically, youth counselors in both work groups agreed that the CRAFFT tool was too technical for use by non-clinicians. As a result, TYSA is moving forward by having the continuum of care workgroup roll out the use of CRAFFT with all professionals, including probation officers, pediatricians, adult and family doctors, school counselors, hospitals and emergency rooms, and child welfare providers.

Simultaneously, the social norms group is rolling out an evidence-based training program that educates coaches, parents, and other people who are in constant contact with youth in how to recognize the signs and symptoms of substance abuse and problem behavior, what questions to ask when having a conversation with youth about their drug or alcohol use, and arms them with the available resources to refer someone who they feel may be displaying such behaviors. The solution reached in this case was not one anticipated at the outset by TYSA steering committee members of the initiative. The rules for interaction, however, ensured that all participants were able to see each other’s needs and act together, simultaneously agreeing on a pair of emergent solutions that serves the community far better than existing approaches implemented by any one organization or individual.

This process of collective seeing, learning, and doing is aptly described by noted author, Atul Gawande, in his book The Checklist Manifesto. Gawande investigated how the construction industry deals with complexity and uncertainty in building skyscrapers. He was amazed to find that the software they use does not itself provide the solution to unexpected problems that arise during construction. Instead, the software merely summons the right people together to collectively solve the problem. For example, if the problem involves electricity, the software notifies the electrician; if the problem is in plumbing, it notifies the plumber; and so on—each person needed to resolve the problem is brought together by the software, but the people themselves figure out the solution.

In his book, Gawande remarks on the irony that the solution does not come from the computer or a single person in authority: “In the face of the unknown—the always nagging uncertainty about whether, under complex circumstances, things will really be OK—the builders trusted in the power of communication. They didn’t believe in the wisdom of the single individual, or even an experienced engineer. They believed in the wisdom of making sure that multiple pairs of eyes were on a problem, and then letting the watchers decide what to do.” Although the construction industry’s approach has not been foolproof, its record of success in relying on emergent solutions has been astonishing: building failures in the United States amount to only 2 in 10 million. While complex social and environmental problems are very different than complex construction projects, Gawande’s investigation illustrates the pragmatic power in relying on emergent solutions.

When the Process Becomes the Solution

We have found in both our research and consulting that those who hope to launch collective impact efforts often expect that the process begins by finding solutions that a collective set of actors can agree upon. They assume that developing a common agenda involves gaining broad agreement at the outset about which predetermined solutions to implement. In fact, developing a common agenda is not about creating solutions at all, but about achieving a common understanding of the problem, agreeing to joint goals to address the problem, and arriving at common indicators to which the collective set of involved actors will hold themselves accountable in making progress. It is the process that comes after the development of the common agenda in which solutions and resources are uncovered, agreed upon, and collectively taken up. Those solutions and resources are quite often not known in advance. They are typically emergent, arising over time through collective vigilance, learning, and action that result from careful structuring of the effort. If the structure-specific steps we have discussed here are thoughtfully implemented, we believe that there is a high likelihood that effective solutions will emerge, though the exact timing and nature cannot be predicted with any degree of certainty. This, of course, is a very uncomfortable state of being for many stakeholders.

And yet staying with this discomfort brings many rewards. The collective impact efforts we have researched are achieving positive and consistent progress on complex problems at scale, in most cases without the need to invent dramatically new practices or find vast new sources of funding. Instead we are seeing three types of emergent opportunities repeatedly capitalized on in collective impact efforts:

- A previously unnoticed evidence-based practice, movement, or resource from outside the community is identified and applied locally.

- Local individuals or organizations begin to work together differently than before and therefore find and adopt new solutions.

- A successful strategy that is already working locally, but is not systematically or broadly practiced, is identified and spread more widely.10

Effective collective impact efforts serve one other important function as well: providing a unified voice for policy change. Vibrant Communities reports that numerous changes in government policies related to housing, transportation, tax policy, child care, food security, and the like have resulted from the power of alignment across sectors that results from the disciplined, yet fluid structuring, of collective impact efforts. In our own experience working with the Juvenile Justice system for the State of New York, a twelve-month collective impact effort to establish an initial common agenda was able to produce clear policy recommendations that have since been signed into law. As our political system increasingly responds to isolated special interests, the power of collective impact to give political voice to the needs of a community is one of its most important dimensions.

Shifting Mindsets

To be successful in collective impact efforts we must live with the paradox of combining intentionality (that comes with the development of a common agenda) and emergence (that unfolds through collective seeing, learning, and doing). For funders this shift requires a different model of strategic philanthropy in which grants support processes to determine common outcomes and rules for interaction that lead to the development of emergent solutions, rather than just funding the solutions themselves. This also requires funders to support evaluative processes, such as developmental evaluation, which prioritize open-ended inquiry into emergent activities, relationships, and solutions, rather than testing the attribution of predetermined solutions through retrospective evaluations.

Such a shift may seem implausible, yet some examples exist. We earlier mentioned that the Gates Foundation is using developmental evaluation to support an effort that provides broad latitude for grantee communities to identify emergent strategies. The Gates Foundation’s Pacific Northwest Division has made a similar shift by supporting the infrastructure for collective impact education reform in nine south Seattle communities. And the Greater Cincinnati Foundation, a key initial champion of the Strive “cradle to career” collective impact education effort in Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky, is now supporting the development of shared community outcomes and backbone organizations in four additional program areas: workforce development, early childhood, community development, and economic development.

Curiosity is What We Need

At its core, collective impact is about creating and implementing coordinated strategy among aligned stakeholders. Many speak of strategy as a journey, whether referring to an organization, a career, or even raising a family. But we need to more fully confront what happens on the journey. Some days we will move quickly as planned, other days we may find our way forward unexpectedly blocked. We will meet new people and develop new ideas about our purpose, and even the coordinates of our destination. Going on a journey is a complex undertaking. Often, the best course of action is to make sure we are closely watching what’s happening at each stage of the way. As Brazilian author Paulo Coelho remarked “When you are moving towards an objective, it is very important to pay attention to the road. It is the road that teaches us the best way to get there, and the road enriches us as we walk its length.”11

Complexity theorists believe that what defines successful leaders in situations of great complexity is not the quality of decisiveness, but the quality of inquiry. As organizational behavior guru Margaret Wheatley puts it, “we live in a complex world, we often don’t know what is going on, and we won’t be able to understand its complexity unless we spend more time not knowing… Curiosity is what we need.”12 Collective impact success favors those who embrace the uncertainty of the journey, even as they remain clear eyed about their destination. If you embark on the path to collective impact, be intentional in your efforts and curious in your convictions.

References

- 1 John Kania and Mark Kramer, “Collective Impact,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, Winter 2011. Fay Hanleybrown, John Kania, and Mark Kramer, “Channeling Change: Making Collective Impact Work,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, January 2012.

- 2 We first wrote about uncertain and unpredictable situations involving multiple stakeholders, in which there is no known answer for the problem at hand, in “Leading Boldly,” by Ronald Heifetz, John Kania, and Mark Kramer in Stanford Social Innovation Review, Winter 2004. We referred to these situations as adaptive problems. Co-author Ronald Heifetz coined the term “adaptive problems” in his seminal body of work on “adaptive leadership.” Complex problems and adaptive problems are essentially different terms describing similar conditions, sometimes also referred to as wicked problems, and all three terms have their foundation in complexity science and its twin discipline, chaos theory. Our own experience, and that of several leading practitioners, has shown that the principles of adaptive leadership are extremely useful in guiding the collective impact process.

- 3 Even in the world of business where business plans are taken for granted, leading strategists such as McGill University professor Henry Mintzberg, have conducted extensive research that demonstrates most corporate strategies are emergent. Companies begin with plans, to be sure, but learn their way into successful business models through trial and error, reshaping their strategies in response to changing conditions, and accumulated experience.

- 4 If you want to be re-inspired by this sight, go to You Tube and search for “Starlings at Ot Moor” in the UK.

- 5 From Frances Westley, Brenda Zimmerman, and Michael Patton, Getting to Maybe: How the World is Changed, Random House Canada, 2006.

- 6 The risk factor of Poor Family Management dropped by 19 percent and Parental Attitudes Favorable to Substance Use decreased 12 percent. See FSG blog by Kat Allen, co-chair, Communities That Care Coalition of Franklin County and the North Quabbin.

- 7 Developmental evaluation is a term coined by the organizational consultant and program evaluator Michael Quinn Patton in the early 1990s.

- 8 Hallie Preskill and Tanya Beer, Evaluating Social Innovation, Center for Evaluation Innovation.

- 9 Preskill and Beer, Evaluating Social Innovation.

- 10 The notion of capitalizing on emergent solutions that come from within has been compellingly depicted by authors Richard Pascale, Jerry Sternin, and Monique Sternin in their book, The Power of Positive Deviance, Harvard Business Review Press, 2010. The authors share provocative examples of “positive deviants” who live and work under the same constraints as everyone else, yet find a way to succeed against all odds. Because the solutions have been developed under existing constraints, they can be applied more broadly by others living and working in the same community without the need for incremental resources.

- 11 Quote appeared in Charles Foster’s The Sacred Journey, Thomas Nelson, 2010. Taken from the character Petrus, Paulo Coelho’s fictitious guide on the road to Santiago de Compostela, in Paulo Coelho’s book, The Pilgrimage.

- 12 Margaret J. Wheatley, Turning to One Another; Simple Conversations to Restore Hope to the Future, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2002, pp. 38-42.