OVERVIEW

MANAGEMENT

PERFORMANCE

POSSIBILITIES

CAPITALS

ACTIVITIES

ACTORS

BURGESS

|

PEOPLE

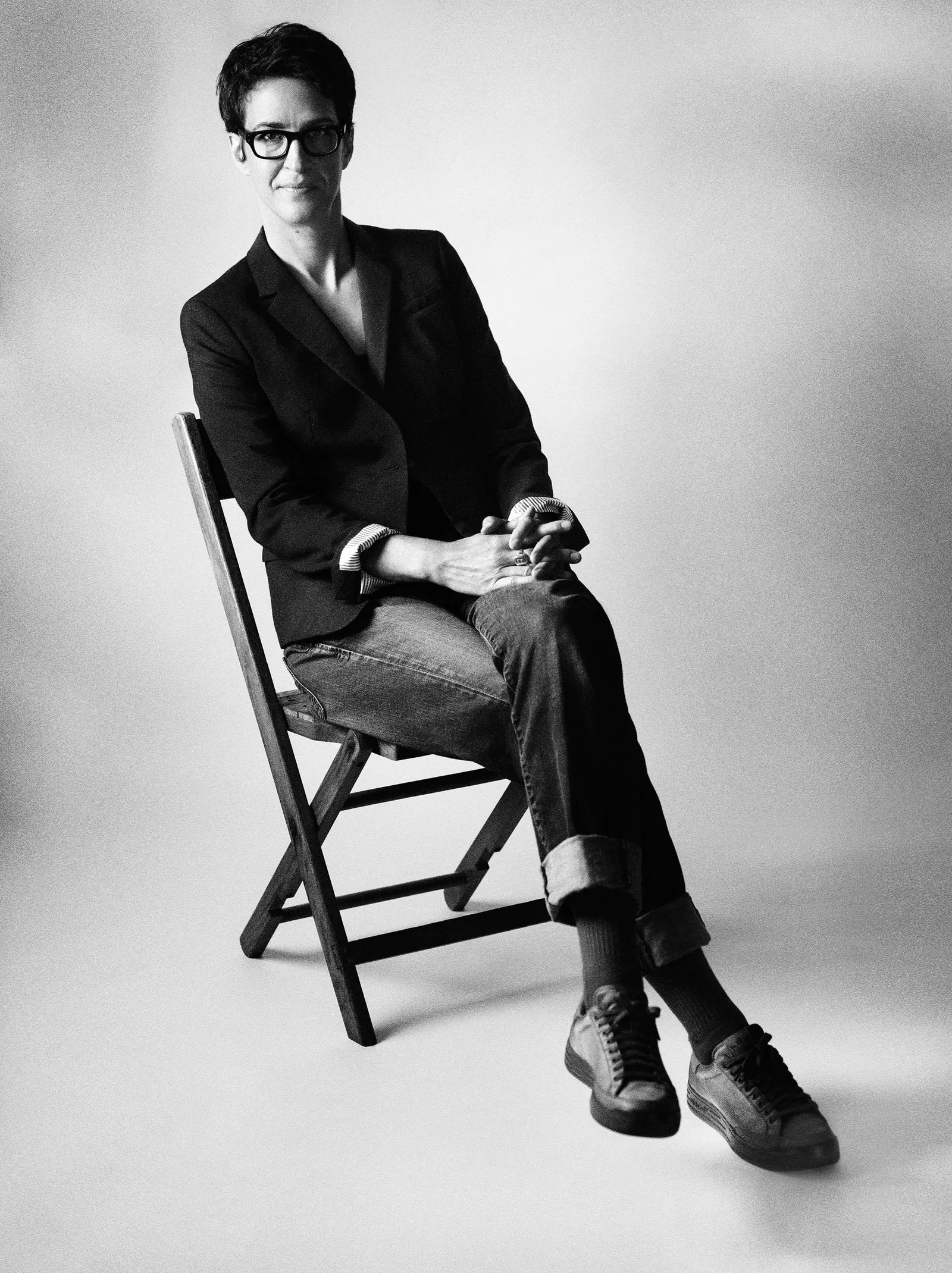

RACHEL MADDOW Rachel Maddow: Trump’s TV Nemesis ... Her show permits liberals to enjoy themselves during what may be the most unenjoyable time of their political lives.

Maddow’s artistry is most conspicuous in her monologues, which can span as long as twenty-four uninterrupted minutes. Photograph by Pari Dukovic for The New Yorker Original article: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/10/09/rachel-maddow-trumps-tv-nemesis Burgess COMMENTARY This is a great article about Rachel Maddow ... for me it captures the essense of what comes over when Rachel Maddow is on air. I don't get to watch her very much any more on TV ... but over the years I have been impressed by a lot of the in-depth stories that she handles. I have always thought that a part of her strength was to do a better job than most program hosts in getting beyond the easy stuff and into what is really going on. Peter Burgess | ||

|

Rachel Maddow: Trump’s TV Nemesis

Her show permits liberals to enjoy themselves during what may be the most unenjoyable time of their political lives. Written by Janet Malcolm ... for The New Yorker October 2, 2017 ... published in Profiles ... October 9, 2017 Issue (Accessed April 2022) In Rachel Maddow’s office at the MSNBC studios, there is a rack on which hang about thirty elegant women’s jackets in various shades of black and gray. On almost every week night of the year, at around one minute to nine, Maddow yanks one of these jackets off its hanger, puts it on without looking into a mirror, and races to the studio from which she broadcasts her hour-long TV show, sitting at a sleek desk with a glass top. As soon as the show is over, she sheds the jacket and gets back into the sweater or T-shirt she was wearing before. She does not have to shed the lower half of her costume, the skirt and high heels that we don’t see because of the desk in front of them but naturally extrapolate from the stylish jacket. The skirt and heels, it turns out, are an illusion. Maddow never changed out of the baggy jeans and sneakers that are her offstage uniform and onstage private joke. Next, she removes her contact lenses and puts on horn-rimmed glasses that hide the bluish eyeshadow a makeup man hastily applied two minutes before the show. She now looks like a tall, gangly tomboy instead of the delicately handsome woman with a stylish boy’s bob who appears on the show and is the current sweetheart of liberal cable TV. Maddow is widely praised for the atmosphere of cheerful civility and accessible braininess that surrounds her stage persona. She is onstage, certainly, and makes no bones about being so. She regularly reminds us of the singularity of her show (“You will hear this nowhere else”; “Very important interview coming up, stay with us”; “Big show coming up tonight”). Like a carnival barker, she leads us on with tantalizing hints about what is inside the tent. As I write this, I think of something that subliminally puzzles me as I watch the show. Why do I stay and dumbly watch the commercials instead of getting up to finish washing the dishes? By now, I know every one of the commercials as well as I know the national anthem: the Cialis ad with curtains blowing as the lovers phonily embrace, the ad with the guy who has opioid-induced . . . constipation (I love the delicacy-induced pause), the ad for Liberty Mutual Insurance in which the woman jeers at the coverage offered by a rival company: “What are you supposed to do, drive three-quarters of a car?” I sit there mesmerized because Maddow has already mesmerized me. Her performance and those of the actors in the commercials merge into one delicious experience of TV. “The Rachel Maddow Show” is a piece of sleight of hand presented as a cable news show. It is TV entertainment at its finest. It permits liberals to enjoy themselves during what may be the most thoroughly unenjoyable time of their political lives. Maddow’s artistry is most conspicuously displayed in the long monologue—sometimes as long as twenty-four minutes, uninterrupted by commercials—with which her show usually begins. The monologue of January 2, 2017, is an especially vivid example of Maddow’s extraordinary storytelling. Its donnée was a Times article of December 31, 2016, with the headline “trump’s indonesia projects, still moving ahead, create potential conflicts.” The story, by Richard C. Paddock, in Jakarta, and Eric Lipton, in Washington, was about the resorts and golf courses that Donald Trump is building in Indonesia and the cast of unsuitable or unsavory characters that have been helping him move the projects along. Among them are Hary Tanoesoedibjo, Trump’s business partner, a billionaire with political ambitions that might put him into high office in Jakarta; Setya Novanto, the Speaker of the Indonesian House of Representatives, who had to resign when he was accused of trying to extort four billion dollars from an American mining company; and the billionaire investor Carl Icahn, a major shareholder in that mining company, who had recently been named an adviser to the Trump Administration on regulatory matters. It was one of those stories about Trump’s mired global business dealings which are themselves marked by Trump’s obscurantism, and which tend to mystify and confuse more than clarify—and ultimately to bore. They have too much information and too little.

“This is the same music my fitness instructor plays for our abdominal crunches.” In Maddow’s hands, the Times story became a lucid and enthralling set piece. “This story is amazing and it starts with copper,” Maddow said at the beginning of the monologue, looking happy. She had already told us that she was glad to be back from her vacation and wasn’t disheartened by the election. People had approached her “with concern in their eyes” and asked how she felt about the coming year. “I found myself . . . saying, ‘I’m really excited for 2017.’ I am! My job is to explain stuff—and, oh my God, is that a good job to have this year!” Maddow then explained the properties of copper. She showed pictures of the Statue of Liberty, pennies, and wires. She talked about the “massive global appetite” for copper electrical wiring, and about a mining company called Freeport, based in Arizona, which is the world’s second-largest producer of copper. One of Freeport’s operations is in Indonesia, where it extracts gold and silver, as well as copper, from a mine that covers almost half a million acres. Maddow showed arrestingly beautiful photographs of the mine’s crater—which is so huge that it is not just visible from space but “easily visible.” She pointed out that the Freeport business in Indonesia is so far-reaching that the company “is the single biggest taxpayer for the whole country. . . . Of all the two hundred and sixty million people in Indonesia, its biggest tax payment every year comes from Arizona.” Why is she telling us this? Maddow anticipates the question. Her acute storyteller’s instincts tell her that this is the moment to show her hand. Without any transition, she says, “In our Presidential election this past year, do you remember when Indonesia had a weird little cameo role?” Of course we don’t remember anything of the sort. Maddow goes on, “It was in the Republican primary. It came up—it was so strange, so unexpected, not just inexplicable but unexplained. . . . It didn’t ever make any sense—until now. I love it when a story doesn’t make sense for a year and then all of a sudden it does.” She is laughing, almost chortling. “It rarely happens when you get it so clearly.” The weird cameo role was played by the then not-yet-disgraced Speaker of the Indonesian House, Setya Novanto. Maddow showed a video of Trump at a press conference at Trump Tower which he had called to announce that he would sign a pledge he had originally refused to sign, promising to support the winning Republican candidate. (All the other Republican candidates had signed it.) At his side was a short, smiling Asian man. “Hey, what’s this random Indonesian guy doing there?” Maddow says. The video goes on to show Trump with his arm around the guy’s shoulders, saying, “Hey, ladies and gentlemen, this is an amazing man. He is, as you know”—as we know?!—“Speaker of the House of Indonesia. He’s here to see me. Setya Novanto, one of the most powerful men, and a great man, and his whole group is here to see me today, and we will do great things for the United States. Is that correct? Do they like me in Indonesia?” The Speaker says, “Yes.” “That was such a random moment in the Presidential election, right?” Maddow says. “It was weird at the time, totally inexplicable. Well, now we get it.” What Maddow has prepared us to get with her geography lesson about copper and the mine in Indonesia is the scandal in which Setya Novanto got caught up, and by which Trump, because of his continuing business relationship with the amazing Indonesian, is tainted. “That mining company that operates a giant open-pit mine that’s the largest gold mine in the world and you can see it from space,” Maddow says, showing a picture of the oversized crater again, and looking enormously pleased with herself, “one of their executives met in Indonesia with that same politician who we just saw with Donald Trump, and he secretly taped him trying to shake down the mining company for four billion dollars.” Freeport’s contract with the Indonesian government runs out in 2021; the company would like to extend it. “The guy who was standing there with Trump, who got introduced at that press conference, that politician was caught on tape telling the mining company that, yeah, he could get them an extension of their contract. In fact, he could get them a twenty-year extension of their contract . . . if they could provide him with a little something.” We learn that the tape was played all over Indonesia, and that Setya Novanto was forced to resign as Speaker. In the end, though, he was reinstated, because the tape was ruled inadmissible as evidence. As Maddow nears the end of her monologue, she mentions the Times story from which she got most of her material: “Donald Trump’s new real-estate deals, that golf course he wants to build . . . the Indonesian resort deals that brought this politician to Trump Tower in the first place, the Trump Organization has just confirmed to the New York Times, those deals are on, those projects are moving forward.” The reader who has been following my own lesson in comparative narratology will notice that Maddow has been sparing in her use of the Times narrative. Many characters that figure in the Times story are missing from Maddow’s, most conspicuously Trump’s Indonesian business partner Hary Tanoesoedibjo. Apart from the not negligible problem of pronouncing his name, Maddow understands the importance in storytelling of not telling the same story twice. The story of Donald Trump and Setya Novanto is enough. You don’t need the additional story of Donald Trump and Hary Tanoesoedibjo to show that Trump’s business dealings are problematic; nor do you need quotations from experts on ethics (the Times cites Karen Hobart Flynn, the president of Common Cause, and Richard W. Painter, a former White House ethics lawyer) to convince us that they are. By reducing the story to its mythic fundamentals, Maddow creates the illusion of completeness that novels and short stories create. We feel that this is the story as we listen to and watch her tell it. As a kind of ominous confirming coda, Maddow holds up the appointment of Carl Icahn as an adviser on corporate regulations. (He has since resigned.) “This new key member of the federal government for whom they have invented a job . . . is the single largest shareholder in that mining company, whose mines in Indonesia you can see from space,” she says. “And now that company will presumably be in an excellent position to do whatever needs to be done to benefit whoever needs to be benefitted. . . . This is apparently what it’s going to be like now. Everybody’s got to pay attention now.”

“What do you think they put on the cat lover’s pizza?” Every so often, a show of Maddow’s fails to please. There was the notorious show of March 14th, when Maddow pitched two pages of Trump’s 2005 tax return that had come her way—“Breaking news”; “The world is getting its first look”—and was all-around pilloried for producing nothing much except a stir about herself. Someone had leaked the first two pages of Trump’s tax form to a financial reporter named David Cay Johnston, who passed them on to Maddow. The pages showed that, in 2005, Trump had made more than a hundred and fifty million dollars and had paid thirty-seven million in taxes. This glimpse only deepened the mystery of the tax returns that Trump has withheld, and had all the signs of being a leak from the White House intended to demonstrate that the President was plenty rich and had paid his taxes. The show was an embarrassment that, interestingly and yet perhaps unsurprisingly, did not embarrass Maddow. The bad press that she received from commentators and newscasters (there was a scathing piece in Slate by its television critic, Willa Paskin, titled “Rachel Maddow Turned a Scoop on Donald Trump’s Taxes Into a Cynical, Self-Defeating Spectacle”) did her no harm. Nothing seems to do anyone harm these days. Maddow’s ratings only rose. She saw no reason to apologize or explain. “I really have no regrets at all,” she said when I pressed her for an admission of miscalculation. “People were mad that it wasn’t more scandalous. But that’s not my fault. I did it right.” This was not the case with the show of October 29, 2014, for which Maddow almost immediately saw reason to apologize. The show began with Maddow placing on her desk, one by one, a graduated set of ceramic kitchen cannisters. “Here in our offices at 30 Rockefeller Center, in our office closet, actually, we have, sort of randomly, a really hideous complete set of kitchen cannisters,” she said, drawing them to her with an impish smile. “A full set of mushroom-ornamented, baby-poop-colored, made-in-China ugly kitchen cannisters. They take up a lot of space, but I can’t get rid of them. We bought these hideous kitchen cannisters when a producer on our staff stumbled upon them while out shopping and realized—photographic memory—that these were an exact match to one of the best campaign-ad props thus far in the twenty-first century. Look.” A picture then appeared onscreen, showing a woman sitting in front of a display of the same mushroom-ornamented cannisters that live in the office closet at MSNBC. The woman was Sharron Angle, a Nevada Republican, who had tried to make a political comeback after an unsuccessful attempt to unseat Harry Reid in his Senate race in 2010. “It wasn’t so much that Harry Reid won that Senate race in 2010,” Maddow said. “It was that Sharron Angle lost that race, because Sharron Angle talked like this.” Maddow then showed a series of statements made by Angle, under headings such as “2nd Amendment Remedies”: I feel that the Second Amendment is the right to keep and bear arms for our citizenry. . . . This is for us when our government becomes tyrannical. . . . And you know, I’m hoping that we’re not getting to Second Amendment remedies. I hope the vote will be the cure for the Harry Reid problem.“I sure hope the vote will be the cure for the Harry Reid problem,” Maddow said, with one of her nicest smiles. “Democrats had no business winning that Senate race in Nevada that year. But Sharron Angle threatening that if conservatives didn’t get the election results that they wanted they would start shooting in order to get the election results that they wanted—that was enough to spook people who might otherwise have supported her. . . . You just can’t run people like that for statewide office.”Angle had evidently learned her lesson, and in her new bid for office—for a House seat this time—she used the Mushroom Cannister Remedy to reassure voters and show that “there was nothing to be scared of when it comes to her.” They could see that she was just another nice, kitsch-loving Republican lady. Not so Maddow’s next character, Joni Ernst, who was running for the Senate in Iowa and now “turns out to have a Sharron Angle problem. A piece of tape has emerged where Joni Ernst, like Sharron Angle before her, is threatening that she is ready to turn to armed violence against the government if she doesn’t get what she wants through the political process.” Maddow showed Ernst at a lectern, saying, “I have a beautiful little Smith & Wesson 9-millimetre, and it goes with me virtually everywhere. But I do believe in the right to carry, and I believe in the right to defend myself and my family, whether it’s from an intruder or whether it’s from the government, should they decide that my rights are no longer important.” (In the end, Ernst won her race, without having to shoot anyone.) Maddow closed the segment with: “I would say watch this space, but I know all you’re watching right now is these hideous kitchen cannisters.” The next night, an unsmiling Maddow addressed her audience thus: “O.K., so last night I may have crossed the line. I went a little too far and said something that offended some of our viewers, and rightly so. It was not my intention to offend. So we’ve got a Department of Corrections segment coming up. Anybody who likes to watch this show because you like to yell at me while I’m on the screen, you will like this next thing that I’m going to have to do. Mea culpa on the way.” Sitting in front of a sign that read “department of corrections,” Maddow recapitulated her narrative of the page Joni Ernst took from Sharron Angle. “Tonight, I have a correction to make about that. I will tell you, though, that this correction has nothing to do with Joni Ernst.” In fact, the “correction” was not a correction at all. Maddow had made no factual errors. She had merely betrayed her youth. She had not lived long enough to know that you do not mock people’s things any more than you mock their weight or accent or sexual orientation. “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful,” William Morris wrote in his famous dictum. Morris knew very well what was hideous. But he knew enough about human nature to insert that inspired “believe.” Maddow’s disparagement of the mushroom cannisters brought her a torrent of mail. She read aloud from it: “I was insulted that you referred to the cannisters as ugly, as I had bought that set many years ago. I wish I still had my cute, adorable cannisters.” “Hey, Rachel, my mother has a set, too—we could use a matching set.” “If by hideous you mean the most awesome cannisters of all time then you are correct.” More messages appeared on the screen: “hideous??? What ever do you mean?” “Those were my grandmas mushroom canisters! She had matching pots, s&p, spoon rest, napkin holder and a wall clock.”

“On Monday, they will introduce a new office layout and you’ll be near Judy, who isn’t good at sharing her charger. Then you’ll finish up a report on whether your client’s edgy new marketing tactics havebeen resonating with the 18-34 demographic. The results will be inconclusive and your boss will say, ‘Jared, there’ll always be another Instagram-based influencer strategy to review,’ but she also takes a while to approve your annual leave request and you will suspect that the two are related. Anyway, that train of thought will be interrupted by a routine fire drill.” “I have been aesthetically swayed,” Maddow said, setting down the sheaf of letters. “Yes, I once believed that those mushroom cannisters were hideous, in the context of threatening armed violence against government officials, à la Sharron Angle in Nevada and Joni Ernst in Iowa. I also do still kind of think they’re hideous here at my office. But in real life, on your shelf, on your kitchen counter, in the recesses of your childhood memories, the Merry Mushroom cannisters your mom bought at Sears in the seventies—which also happened to match your Merry Mushroom curtains—those mushroom cannisters really aren’t hideous. They are lovely. So thank you for fact-checking me on this. I sincerely regret what I now believe is an error. I love your mushroom cannisters and your kitchen—I love all of it.” She had been hugging the biggest cannister. Now she removed its lid and put it on her head. “Sorry.” Maddow was born forty-four years ago in the small city of Hayward, in the San Francisco Bay Area, and grew up in neighboring Castro Valley. Her brother, David, now on the staff of a bioscience company, was born four years earlier. Her father, Robert, a lawyer, worked as the counsel for the local water company, and her mother, Elaine, had an administrative job in the school district and wrote for a community newspaper. “I had a middle-class, suburban upbringing,” Maddow told me. “I graduated from the local high school at seventeen and went to Stanford. I came out soon after I got to college, and that caused a rift—a temporary rift—with my family. It was very hard for them. My mom is very Catholic, and my dad saw how much it hurt my mom. But now my parents and I are close again. They couldn’t be more supportive. They’re very close to my partner.” Maddow’s partner is Susan Mikula, a fifty-nine-year-old artist, with whom she has lived for the past eighteen years. They met in a small town in Massachusetts, in the western part of the state, a few years after Maddow graduated from Stanford. She was writing her thesis for an advanced degree from Oxford, where she had studied as a Rhodes Scholar. (She had also received, as not many applicants do, a Marshall Scholarship.) “I wanted to be in an unhappy living situation to get the thesis done,” she said. She supported herself by doing odd jobs, and word of one of these jobs brought her to the door of Mikula, who was looking for someone to do yard work. When Mikula opened the door, a coup de foudre followed. Maddow had been an athlete in high school. Her sports were volleyball, basketball, and swimming. In her senior year, she badly injured her shoulder playing volleyball and was faced with a difficult choice. “I was a good athlete,” she told me. “I wouldn’t say I was a great athlete, but I was good, and I was scouted by a number of schools for an athletic scholarship. When I hurt my shoulder, I had to decide whether to get it fixed so I could go on being an athlete, or not. To get it fixed meant surgery and rehabilitation and starting college a year late. I decided not to get the shoulder fixed—it works perfectly well in regular life—and to go to college right away. Stanford, which had the best teams in the country in my sports, would not have given me an athletic scholarship anyway. “Around this time I was realizing I was gay. I was coming out to myself. And, having grown up in this conservative town in the Bay Area with my relatively conservative Catholic parents, I knew this was not a place I wanted to be a gay person in. When I realized I was gay—it’s not that I hadn’t had inklings—when it finally clicked into place, I was, like, ‘Oh! That’s it. That’s what I am!’ There was no ambiguity about it. It was an epiphany. It was the same thing when I met Susan. I know that people don’t believe in love at first sight. It was absolutely love at first sight. Bluebirds and comets and stars. It was absolutely a hundred per cent clear.” I asked Maddow if coming out to herself was preceded by feelings about a particular woman. She said, “No. It was much more an intellectual thing.” It was a thing that brought her into aids activism. The epidemic was then in its darkest period. Maddow worked in hospices and with organizations helping prisoners who had the disease. “We were taking this overwhelming, maddening, depressing, very sad thing that my community and my city were going through and figuring out what pieces of it we could bite off and fix, finding winnable fights in something that felt like a morass and was terrible,” she said. This work continued throughout college and graduate school and culminated in her doctoral thesis, on H.I.V. and aids reform in British and American prisons.

“Our son, Jeffrey—right now he’s living with us, but eventually he plans to move to one of those newly discovered planets that are capable of supporting life.” Maddow spoke of her detachment from what she calls “electoral politics” during the time of her aids activism. She recalled giving money to Harvey Gantt, who was running against Jesse Helms in the 1990 North Carolina Senate race, because of Helms’s homophobic position on aids. “That was the closest I came to having an electoral-politics impulse,” she said. “I didn’t have strong feelings about Republicans and Democrats. In some ways, I still don’t.” “Even with what the Republican Party has become?” I asked. “I’m very interested in the conservative movement and in what the Republican Party has become,” Maddow said. “I think I am a liberal. I believe that government is a manifestation of the social contract. It’s a way we ought to work together as our best selves to make things better for the least among us and improve society as a whole. But I’m almost more interested in the sociology of conservative and liberal styles, particularly of conservative styles. I think the conservative movement is fascinating and arcane. The dynamic between the conservative movement and the Republican Party—of which there is no parallel on the left—is a really interesting ongoing saga that has incredibly sharp turns in it. And the people who are inside this movement are often very bad observers of what is happening. Which is nice for me, because being definitely on the outside gives me a better perspective on it. I happened to have a fascination with crazy right-wing racist politics—and all of a sudden that’s relevant. It’s my moment.” I think I am a liberal. Why the equivocation? It may derive from the restless politics of Maddow’s parents. “When I was growing up, both my parents were centrists. They were Reagan Democrats—Democrats who voted for Reagan,” she said. “But during the George W. Bush Administration my dad became a motivated liberal. Dick Cheney in particular made my dad into a liberal. My mom less so. But when Schwarzenegger was elected governor in California, in 2003, I remember her saying, ‘I feel like I don’t have a President, I don’t have a governor, and I don’t have a Pope.’ ” Maddow’s entrance into broadcasting began as a lark. While she was writing her thesis and doing her odd jobs in western Massachusetts, she heard about an audition held by a local radio station for someone to announce the morning news. She got the job—understandably. She has a beautiful voice, low in register but with a clarion brightness to it, and beautiful diction. This job led to others, to higher and higher rungs on the ladder of radio broadcasting (the liberal network Air America was her final radio destination, in 2004), and then to work in television news at MSNBC and, ultimately, to her own show, which began airing in 2008. When I went to observe Maddow doing her broadcast, at MSNBC’s headquarters, in Rockefeller Center, I didn’t know what to expect, but I was unprepared for the large, eerily silent studio, some of whose props I recognized from watching the show—the desk with the glass top, the garish views of Manhattan skyscrapers. At five minutes to nine, the studio was empty except for me and a young man who had come to bring me earphones. At four minutes to nine, a calm young woman appeared and adjusted the large cameras that faced the desk. At a few seconds before nine, Maddow rushed in and sat down at the desk. She performed her long opening segment. During commercials, she typed furiously on a small computer. Watching her performance at home can be an exhilarating experience. Watching it in the studio was a somewhat flat one. Maddow went through her paces, but they were paces. A few days later, I visited a room—called the control room—a floor below the broadcasting studio, where seven people sit in front of futuristic-looking computers and carry out the work of illustrating Maddow’s commentary with photographs, videos, and writings. They all seem to know what they are doing, but they do not seem relaxed. Things can go wrong, and they sometimes do. The wrong illustration can appear, for example, and Maddow has to react to it with practiced grace and humor. The hour of the show is the culmination for Maddow of a workday that starts at around 12:30 p.m., when she acquaints herself with the day’s news. At two o’clock, she meets with her staff of twenty young men and women in a room equipped with a whiteboard and two facing rows of identical small desks. The day that I came to a meeting, Maddow arrived ten minutes after the hour, dressed in jeans and a black sweater. She stood in front of the whiteboard, which displayed a list of possible subjects for the show. An elliptical exchange about the various items followed. Maddow would ask a question, and someone would answer. She was informing herself about the possible stories. By the time of the meeting, “I have a pretty good idea of at least what is in contention for making the show that night. I already have two or three ideas. But by the end of the meeting I’ve usually changed my mind,” she said. “It’s a grumpy meeting. A little testy.” I noticed none of this at the meeting I attended; I just found it hard to follow.

“It’s Eden. You don’t have to keep checking for ticks.” “Do you start writing your text after the meeting?” I asked. “No. I start reading. I read far too long after the meeting. I know what will be in the show, but I haven’t read enough detail, and I don’t start writing until it’s too late.” “What time do you start writing?” “I should start writing at four-thirty. Sometimes I don’t start writing until six-thirty.” I told her how impressed I was that she can write her substantial monologue in such a short time. “It’s a bad process. It’s impressive in one way, but it’s—reckless. It kills my poor staff. They’re so supportive and constructive. But it’s too much to ask. They need to put in all the visual elements and do the fact-checking and get it into the teleprompter. It’s a produced thing and requires everybody to do everything fast. And it’s a broken process. If I could just get it done an hour earlier, I think I would put ten years back in the lives of all the people who work with me.” I asked her why she didn’t start work earlier in the day.

“Don’t worry—I had one of those when I was a kid, but eventually he just drifted away.” Part of the problem, she told me, is that the news changes in the course of the day. But she has a more compelling reason for starting work at noon: “I’ve tried starting at nine. It’s not that I have anything so important going on in my life that I wouldn’t trade it to be better at my job, but it’s that you can only have your brain lit up for that long before it starts to break down and you stop making sense and stop being creative. What I don’t want to give up is the originality.” She went on, “The thing that defines whether or not you’re good at this work is whether you have something to say when it’s time to say something. Because you’re going to have to say something when that light goes on. I could roll in at eight o’clock and have my producers tell me what to say and book seven people for me to chat with about the news. There are people who have made a very successful living doing that in this work. I just don’t want to do it that way. I want to have something to say that people don’t already know every single night, every single segment, and that makes it hard to get the process right, because that’s the only thing I care about.” I asked her what she did in the morning hours, before she turned on the light switch for her brain. “I’ll go to the gym, or spend time with Susan, or sometimes, when the weather is nice, I’ll go fishing before I go to work. I try to do something that is definitely not work,” she said. The writing of her sobering book, “Drift: The Unmooring of American Military Power,” published in 2012, was another “not work” activity—as were her interviews with me. She would come to my apartment (she preferred this to meeting in the furnished sublet that she and Susan had had to move into after a fire in their own apartment destroyed most of the interior and many of their possessions) and we would talk for an hour or an hour and a half. Maddow has given many interviews, several dozen, and when I told her that I had read some of them she was curious about my reaction. I said that everyone said pretty much the same things about her personal life (as I expected to do myself). “Does that surprise you?” I asked. “No, it is my sense as well,” she said. “I have a private life and a private me that is separate and apart from what is on television. I go on television and I do this thing and it’s real, it’s part of me, but it’s not all of me. The rest of me is my own. It’s not for everybody else. You sort of pick a slice of your life that you’re going to share as your non-TV persona and you give that to people—and they find it more or less interesting.” Maddow has suffered from depression since childhood, and a few years ago she decided to allow this affliction a place in her non-TV persona by speaking about it in interviews. “It was a hard call,” she said. “Because it is nobody’s business. But it had been helpful to me to learn about the people who were surviving, were leading good lives, even though they were dealing with depression. So I felt it was a bit of a responsibility to pay that back.” The depression comes in cycles. She doesn’t know how long a bout of depression will last—it can be one day or three weeks. She takes no medication, but expects that one day she will have to—“I will not have a choice.” But she dreads the thought of “a change to the psyche.”

“First thing, Toby—just bend your knees a little and get rid of the cigarette.” “Is there a manic side?” I asked. “Yes, but much less than when I was young. That has flattened a bit.” “Have you had psychotherapy?” “No.” “Are you afraid of changes to the psyche it might produce?” “No. I’m just not interested. I’m happy to talk to you for this profile, because I’m interested in you and in this process. But, in general, talking about myself for an hour—it’s not something that I would pay for the privilege of. It just sounds like no fun.” Maddow’s TV persona—the well-crafted character that appears on the nightly show—suggests experience in the theatre, but Maddow has had none. “I am a bad actor. I can be performative. But I can’t play any other character than the one who appears on the show. I can’t embody anyone else.” To keep herself in character, so to speak, Maddow marks up the text that she will read from a teleprompter with cues for gestures, pauses, smiles, laughs, frowns—all the body language that goes into her performance of the Rachel figure. “My scripts are like hieroglyphics,” she said. I asked her if I could see a page or two of these annotated texts. She consented, but then thought better of it. “Does the name Ben Maddow mean anything to you?” Maddow asked during one of our early interviews. “Yes, it does,” I said. In the early eighties, I had read a brilliant book—an illustrated biography of the photographer Edward Weston—by a man of that name. The book gave no information about him to speak of, and I did not seek it out, though I was curious. In the eighties, curiosity about authors was less urgent, perhaps because the New Criticism was still a force to reckon with, or, probably, more to the point, because there was no Google to instantly gratify it. So, when Rachel Maddow became a household name, it didn’t summon the name of Weston’s biographer. But now that she uttered it, and said he was a distant relative about whom she knew very little, I hastened to press the keys that would tell me who he was. I learned that he died in 1992 and is largely remembered today as a left-wing Hollywood screenwriter, who wrote or collaborated on such classics as “The Asphalt Jungle,” “Intruder in the Dust,” and the documentary “Native Land,” and was blacklisted between 1952 and 1958. After graduating from Columbia, in 1930, he was unemployed for two years and finally found a job as a hospital orderly and then one as an “investigator” for a Roosevelt-era agency called the Emergency Relief Bureau. He found his calling, and learned his trade as a screenwriter, when he joined a fellow-travelling collective called Frontier Films to work on documentaries. While studying at Columbia, Ben had been a protégé of the poet and critic Mark Van Doren, and began publishing poetry in little magazines. “My poetry was pretty dreadful, so exaggerated,” he told Pat McGilligan, the author of “Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s.” He adopted the nom de plume David Wolff because, as he told McGilligan, “I didn’t want the people at the Bureau to think that somehow I was uppity.” In 1940, his long poem “The City,” published in Poetry under the David Wolff pseudonym, was awarded one of the magazine’s major prizes, which later went to, among others, Robert Lowell, Ezra Pound, and W. S. Merwin. Allen Ginsberg said the poem influenced him in the writing of “Howl.” It is long forgotten. It may be one of the most dreadful poems ever written, worthy of inclusion in “The Stuffed Owl: An Anthology of Bad Verse,” a collection that Wyndham Lewis and Charles Lee published, in 1930, to universal delight. It is hard to choose a typical example among the poem’s twenty-seven stanzas. They all read sort of like this: Black halloween! I walked with the crooked nun;After six years on the blacklist and working “in the shadows,” as it was called, Maddow caved in and named names to the House Un-American Activities Committee. McGilligan reports this reluctantly and sadly. As he had observed when interviewing Ben—and as I had inferred from the Weston biography—Ben was an exceptionally interesting and civilized man. Leafing through my copy of the biography, I am struck anew by its quality of mildly exasperated tenderness toward its subject. Why am I telling you this? When I told Rachel of my fascination with Ben Maddow and of my feeling that by inserting him into a piece that was supposed to be about her I was imitating her forays into left field, she nodded in agreement. “It’s our form of exhibitionism,” she said. “Here’s what I’m interested in. Here’s what grabs me. I’ll pull you along on the same thread I followed. I think it works. As long as people are connected to you as the author, it works.” The thread I am pulling is attached to a “family secret” that Rachel casually revealed to me one morning. She said that Maddow—with its mild subliminal association of meadows in summer—is a fake name. Not faked by her or her parents but by a nineteenth-century Ellis Island official who bestowed it on a family of Russian Jewish immigrants named Medvyedov, derived from medvyed, the Russian word for “bear.” One of the few things Rachel has been told about her kinsman Ben is that he chose David Wolff as his pen name because he thought medvyed meant “wolf.” Rachel’s paternal grandfather, Bernard, came, like Ben, from this renamed family. He grew up in New Jersey, and became a jeweller. Shortly before the Second World War, he married a woman from a Dutch Protestant family named Gertrude Smits. Rachel speculates that Gertrude’s parents were “not psyched about Trudy marrying a Jew, so this became a subject that was not discussed in the family. It wasn’t exactly a family scandal, but it was close to a family secret that Grandfather was Jewish.” Rachel’s father, Robert, was brought up as a Protestant. When he and the “very Catholic” Elaine were engaged, he agreed that their children would be brought up in her faith. He converted to Catholicism when Rachel was eight years old. Maddow recalled that around ten years ago, when she and her brother were home for a holiday, her mother made a formal announcement: “ ‘You know, your grandfather was Jewish.’ And David and I were, like, ‘Yeah?’ My parents thought they were breaking news to us, but my brother and I had known Grandfather was Jewish for a very long time, though we didn’t know how we knew.” In 1938, when Bernard and Trudy married, anti-Semitism was still a fact of life in America, like soda fountains in drugstores. Words like “mishegaas” and “shpilkes,” which trip from Rachel’s tongue in her broadcasts, were never heard in Edward R. Murrow’s. The revelation that someone you didn’t know was Jewish was Jewish was breaking news of a sort. Today, it is something that is apt to receive a “Yeah?” response. And yet, and yet. As Rachel spins her elaborate tales out of the threads the news provides, so I have spun my tale of the mysterious Ben Maddow and the covertly Jewish grandfather out of the threads she had offered in a forthcoming moment. The story remains unsatisfying. Ben Maddow remains hidden. My respect for Rachel’s powers of storytelling is only redoubled by my sense of the absurdity of attempting to imitate her. She is inimitable. Maddow’s excitement about 2017 has died down. She is as disarming and funny as ever, but sometimes the gaiety seems a little forced. Here and there she is magnificent. In a show on June 30th, which could be called “An Essay on Disgust,” she lashed out at Donald Trump as she had never done before. The occasion was Trump’s distasteful attack on two MSNBC commentators, Joe Scarborough and Mika Brzezinski. Maddow set up her argument by talking about the political tool of distraction. Typically, a politician who wants to divert attention from a subject he prefers the public not be overly interested in will introduce another subject that will act the way a glittering toy acts on a susceptible baby. But Trump, she said, “doesn’t just merely distract people, he disgusts people. He breaks the bounds of decency. Breaks the bounds of what people generally agree are the moral rules for engagement in public discourse.” The extremity of Trump’s offensiveness forces us to take the bait, to “weigh in as being opposed to this vile thing. . . . With a normal politician’s normal political distraction, almost all of us will just observe it, right? We’re either distracted by it or we’re not. This guy’s strategy, though, it is really different. It’s to sort of tap on the glass of your moral compass—‘Is this thing on?’ To try to make you feel implicated by your silence.” She went on to speak of the damage Trump does with his “nuclear version of a conventional political tactic.” She said, “The thing he damages is something he neither owns nor particularly values, in the abstract, at least. The thing he hurts is the Presidency and by extension the standing of the United States of America.” Reading the text of the essay is a lesser experience than watching Maddow deliver it on the air. Its logic is a bit insecure, and it is repetitive. But during the broadcast you felt only the force of Maddow’s moral conviction. She is no longer a practicing Catholic, but she has a religious temperament. “I grew up in a believing Catholic home and that has stuck with me,” she told me. “I believe in God, and I probably consider myself Catholic. And I think that in the most basic sense we have to account for our lives once they are done. I don’t have a cartoonist’s picture of Heaven that governs my actions, but I do think you have to make a case for yourself.” This was part of her answer to a question I asked about a commencement speech that she gave at Smith College, in 2010, in which she characterized the saloon-smashing prohibitionist Carrie Nation as “an American huckster, just promoting herself,” who had done the country irreparable harm. She counselled the students to seek glory—the glory of making selfless ethical choices—not fame. That her own quest for glory has brought fame in its wake may be a paradox that occasionally strikes her, but does not put her into a state of high shpilkes. ♦ A previous version of this article misstated Susan Mikula’s age. Published in the print edition of the October 9, 2017, issue, with the headline “The Storyteller.” Janet Malcolm began writing for The New Yorker in 1963. She was a staff writer at the magazine until her death, in 2021. © 2022 Condé Nast. All rights reserved. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our User Agreement and Privacy Policy and Cookie Statement and Your California Privacy Rights. The New Yorker may earn a portion of sales from products that are purchased through our site as part of our Affiliate Partnerships with retailers. The material on this site may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, cached or otherwise used, except with the prior written permission of Condé Nast.

| The text being discussed is available at | https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/10/09/rachel-maddow-trumps-tv-nemesis and |