Date: 2024-04-29 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00009028

Country ... Russia

Economy - January 2015

Inequality and the Putin Economy: Inside the Numbers

Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/putins-way/?elq=fd0cd787900343729b3d47c7abbaaf01&elqCampaignId=1158

Inequality and the Putin Economy: Inside the Numbers

Throughout his time in power, Vladimir Putin has promised to level the playing field in Russia, with an emphasis on growing the middle class. In 2008, he described the gulf between rich and poor as “absolutely unacceptable,” and in 2012 he wrote that “The differentiation of incomes is unacceptable, outrageously high … Therefore, the most important task is to reduce material inequality.”

Three years later, however, inequality remains among the the most stubborn challenges facing the Putin economy. The gulf between between the nation’s ultra-wealthy and everyone else is so extreme, Credit Suisse concluded in a recent report, that “it deserves to be placed in a separate category.” Here is a brief snapshot:

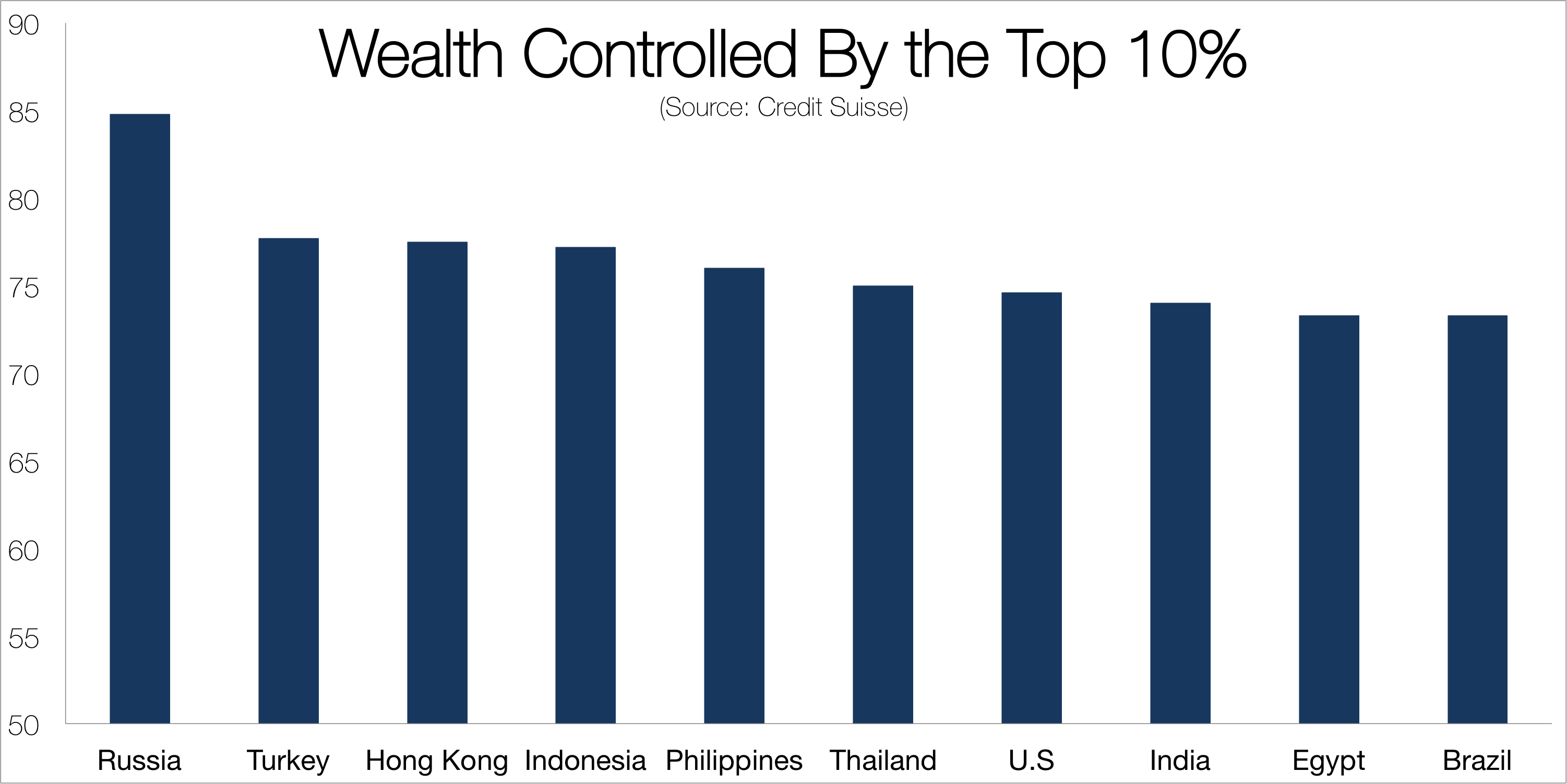

111 people control 19 percent of all household wealth in Russia If there is one statistic that underscores the depth of wealth inequality in Russia, it may be that an estimated 111 billionaires control nearly a fifth of all household wealth in the country. That’s according to the 2014 Credit Suisse analysis, which found that those in the top 10 percent of the population control a staggering 85 percent of wealth in Russia.

Worldwide, there is about one billionaire for every $170 billion in household wealth; in Russia, there is one for every $11 billion.

90 percent of entrepreneurs say they’ve experienced corruption One factor widely seen as contributing to the rise of the uber-rich is the role of corruption inside Russia. Despite pledges by Vladimir Putin to crack down on corruption, to most Russians, the problem remains widespread. Surveys by OPORA, a Russian business association, have found that 90 percent of entrepreneurs have encountered corruption at least once. Among households, corruption ranked as the second biggest problem in the country — behind housing — in a survey by the Institute of Contemporary Development in Moscow.

Perceptions are equally troubling when Russia was compared against international peers such as Brazil, China, India and the 34 member nations of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. In 2014, Russia ranked lower than each in Transparency International’s annual corruption perceptions index. Worldwide, it came in at 136 out of 174.

It’s difficult to put a price tag on the economic costs of corruption, but according to one analysis by the INDEM Foundation, a Moscow-based think tank focused on anti-corruption, the practice costs the nation’s economy between $300 billion and $500 billion each year. With a GDP of about $1.5 trillion, that represents roughly a third of Russia’s economy.

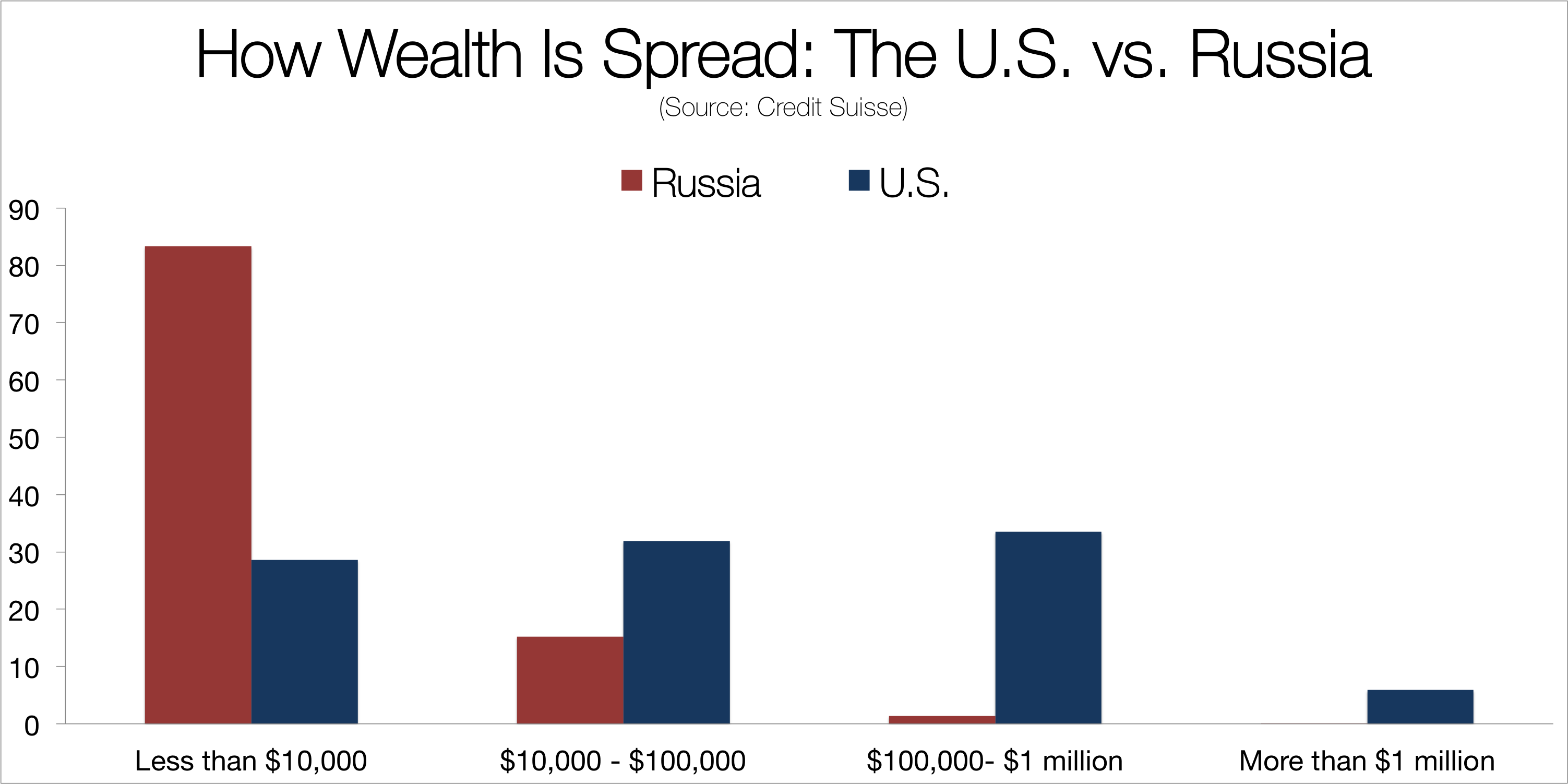

Four out of five Russians have less than $10,000 in wealth

In addition to Russia’s 111 billionaires, it is home to 158,000 millionaires. But for the rest of the nation of 139 million, the Credit Suisse analysis put median wealth at $2,360 in 2014, up from $871 the year before. To be sure, missing data meant that the report’s authors could not factor for real assets — such as how much a person may own in property. But after estimating what those costs may be, the analysis suggests that 83 percent of the population has less than $10,000 in personal wealth.

The energy sector is fueling income disparity

Looking at inequality from the standpoint of income — what someone earns, as opposed to what their personal wealth may be — highlights another challenge facing the Putin economy: the role of the nation’s energy sector in fueling income disparities.

The average middle-class Russian earns between $4,000 and $10,000 per year, according to a 2012 Forbes analysis of data from Rosstat, the nation’s statistics bureau.

But research by the International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth has found that income gains in recent years have primarily benefited Russia’s wealthy energy hubs, while bypassing the nation’s poorest areas. The research showed that in regions where at least half of economic output comes from the oil, gas and minerals industries, incomes are one-third higher, on average, than in the rest of Russia. Four of the five highest-income regions in the analysis were centers of oil and gas production, and all were home to the greatest income inequality. As the study noted:

The growth in … incomes does not reflect growth in entrepreneurship or innovation though. The inequality in the distribution of incomes reflects the economy’s dependence on rents from resource extraction, which has increased incomes in the highest income brackets and hindered the expansion of the middle class.

The middle class has grown anyway

Despite the gulf between the earnings of the ultra-wealthy compared to everyone else, the average Russian salary has grown enough to place a majority of the nation firmly in what the World Bank defines as the middle class. From 2001, Vladimir Putin’s second year as president, to 2010, Russia’s middle class grew from 30 percent of the population to 60 percent, one of the highest rates among emerging economies.

But “middle class” is a relative term, and if there’s one caveat to that figure, it’s that the World Bank sets its threshold for middle class as anyone who lives on at least $10 per day. Moreover, the growth in average wages has been skewed, dramatically at times, by surging incomes at the very top of the income ladder, according to Thomas Remington, a professor of political science at Emory University and author of The Politics of Inequality in Russia.

“The way I look at the middle class, and it’s true for the U.S. too, is if you include the top 10 percent, or the top 5 percent or 1 percent, you can say incomes in the middle class are growing,” he said. “But that’s not the middle class. Those people at the top, the oligarchs, they aren’t the middle class anymore than Warren Buffett is in the middle class in the U.S.”

But staying in the middle class can be tenuous

The rise of the middle class has coincided with a sharp drop in poverty rates. Poverty — which the World Bank defines as anyone living off $5/day or less — fell from 35 percent in 2001 to 11.9 percent by the end of 2013.

But not all households have moved evenly up the social ladder. From 2001 to 2005, and then again from 2006 to 2010, about 15 percent of the population suffered big enough setbacks to push them into worse financial shape, “suggesting that vulnerability to shocks remains an issue at all socio-economic levels,” according to the World Bank. In 2010, for instance, 30 percent of Russians who were considered middle class just five years earlier were financially vulnerable or even poor.

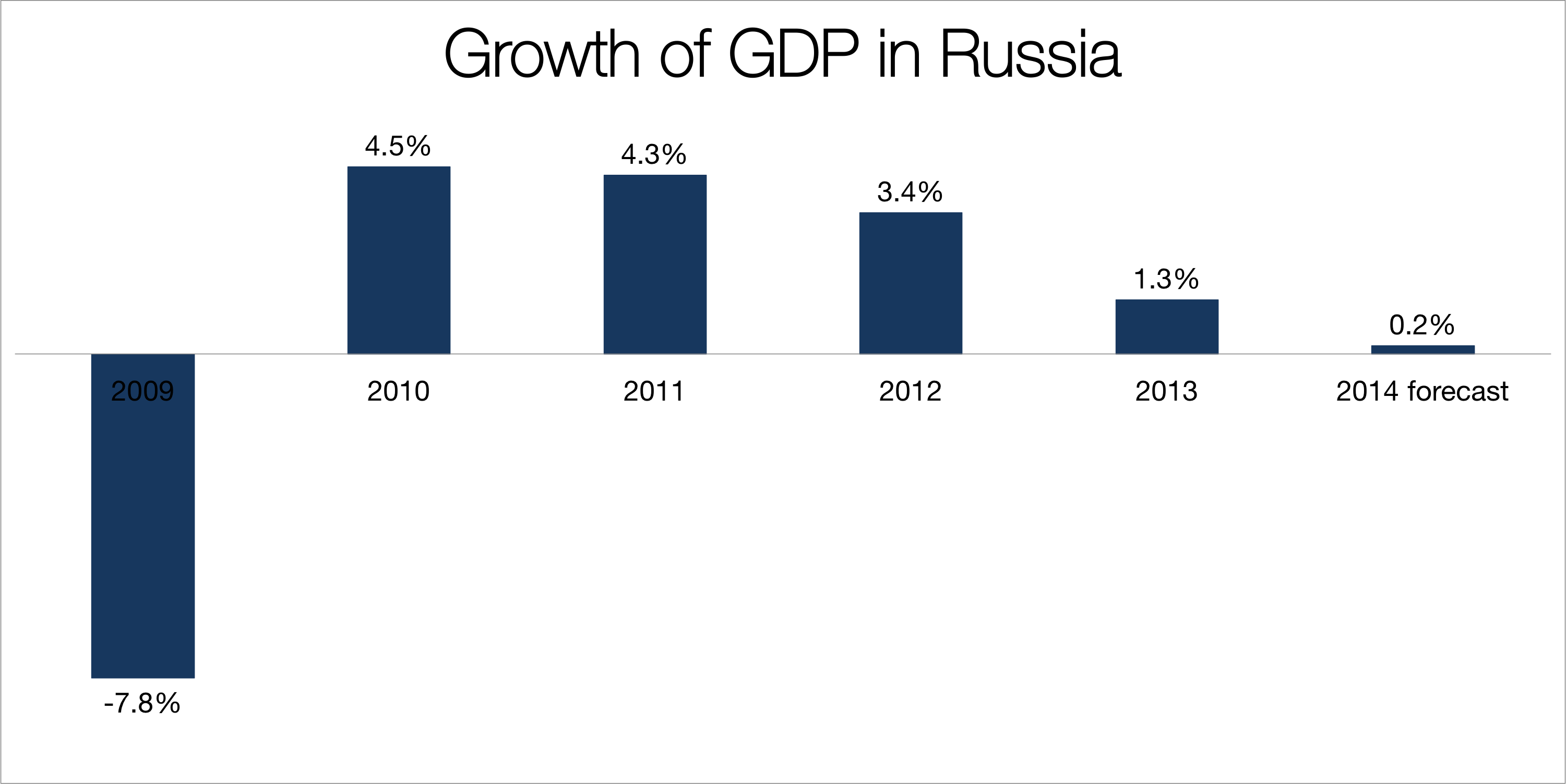

Economic headwinds have arrived

Despite a growing middle class and the decline in poverty rates, 2015 could pose one of the toughest tests to date for the Putin economy. Oil and gas exports account for about half of Russia’s budget revenue, but with oil prices currently trading near five-year lows and the bite from international sanctions keeping the ruble near similar lows against the dollar, Russia’s economy appears set to slide into recession in the months ahead. To make matters worse, consumer prices are expected to rise by double digits, putting additional pressure on already strained household budgets.

The question is, what happens if recession does hit? As prime minister from 2008 to 2012, Putin made expanding the middle class a national priority. But in the aftermath of mass demonstrations against him in 2012, his rhetoric on strengthening working-class families has become noticeably quiet, according to Remington.

“He switched tack,” Remington told FRONTLINE. “His whole strategy is now not promoting the interests of the middle class, but the interests of lower classes and small town people, people in industrial towns that need the state to prop them up … He’s not interested in building the middle class now in his political strategy because he thinks the middle class is ungrateful.”

A woman chooses purchases next to a kiosk selling T-shirts with a portrait of the Russian President Vladimir Putin at a Christmas market in St.Petersburg, Russia. The sign on the T-shirt signs 'Putin is ( all right )'. (AP Photo/Dmitry Lovetsky)