Date: 2024-04-28 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00002968

Metrics

The Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI)

The Genuine Progress Indicator - A Principled Approach to Economics ... The Pembina Institute ...

COMMENTARY

Discontent about the relevance of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as an indicator of social and economic performance is not new ... it did not emerge in response to the financial sector meltdown of 2007/2008 but a long time ago. In fact John Maynard Keynes (U.K.) warned soon after its creation that GDP should only be used for rather limited purposes and the co-creator Simon Küznets (U.S.) spoke out later in 1962 that something better should be used.

This paper was prepared in 1999 at a time when the 'dot.com' bubble was giving the impression that everything was right with the world economy, the stock markets and GDP growth. Not surprisingly nobody paid much attention.

If at first you don't succeed, try, try and try again. Now is the time to build on all this work and establish a ubiquitous system of appropriate metrics ... TrueValueMetrics / Breakthrough Accountancy plan to be part of the success of this system of metrics.

Peter Burgess

The Genuine Progress Indicator — A Principled Approach to Economics

The architects of the GDP — John Maynard Keynes (U.K.) and Simon Küznets (U.S.) — did caution against using GDP as a measure of the welfare of a nation. In 1962 Küznets lamented that 'the welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income as defined by the GDP…goals for 'more' growth should specify of what and for what.'

Some 32 years after Simon Küznets' lament, Redefining Progress was established to address the challenge Küznets posed. This economic research think tank developed the Genuine Progress Indicator, or GPI.

Developed by Clifford Cobb, and co-authored by Ted Halstead and Jonathan Rowe, the 1994 U.S. GPI results created a minor tremor in the U.S. economic machine.

Genuine progress was considerably different than years of torrid economic growth. For the first time, a holistic measure of the welfare of a nation had been constructed — revealing the true state of the nation's natural, social, human and human-made capital.

Mainstream media were lukewarm about these new ideas, wondering what the GPI had to do with the Dow Jones Industrial Average reaching new phoenix highs. For a nation so obsessed with economic performance, this cold shower was strange but honest.

Today, the economic mantra that more economic growth (more production; more consumption) and increasing productivity automatically leads to improved well-being, continues despite an honest accounting of the state of real wealth.

The text of the article follows

The Genuine Progress Indicator - A Principled Approach to Economics

By Mark Anielski

Coca-Cola wouldn't be in business today if it measured corporate performance and ignored the value of depreciating assets the way nations measure economic performance using the gross domestic product (GDP). The GDP (and its predecessor the Gross National Product - GNP), a legacy of John Maynard Keynes, is the broadest measure of economic well-being used by nations and states. Whenever national or provincial economies release their GDP data, Wall Street and Bay Street pundits and the media cheer when the GDP goes up - and boo when it goes down. What this really means is that Americans have been on an exponential consumption and production binge since 1950.

The GDP is like a faulty calculator that can only add the transactions in an economy without accounting for the benefits and costs of real wealth - natural, human and social - that are the foundation of genuine well-being. Adding insult to injury, money - the unit of value of the GDP - is an illusion ('fiat') that bears no relationship to real wealth. Today's money is primarily debt-money (created mostly by private banks) and is literally created out of nothing. However, it extracts a heavy toll as a claim against real capital.

The sins of GDP include ignoring the significant value of unpaid time spent in volunteering, parenting, housework and leisure. The GDP does not account for the cost of crime, family breakdown and rising income inequality. In fact, it includes the expenditures around such activities of social cohesion in the GDP figures. Furthermore, it ignores the value and depreciation of natural resources and the degradation of the environment. As Robert Kennedy once noted, '(GNP/GDP) measures everything except that which makes life worthwhile.' The GDP figures light up on our economic guidance systems like chronic 'happy faces' even though the real foundation (natural, human and social capital) may be eroding. The architects of the GDP - John Maynard Keynes (U.K.) and Simon Küznets (U.S.) - did caution against using GDP as a measure of the welfare of a nation. In 1962 Küznets lamented that 'the welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income as defined by the GDP…goals for 'more' growth should specify of what and for what.'

Some 32 years after Simon Küznets' lament, Redefining Progress was established to address the challenge Küznets posed. This economic research think tank developed the Genuine Progress Indicator, or GPI. Developed by Clifford Cobb, and co-authored by Ted Halstead and Jonathan Rowe, the 1994 U.S. GPI results created a minor tremor in the U.S. economic machine. Genuine progress was considerably different than years of torrid economic growth. For the first time, a holistic measure of the welfare of a nation had been constructed - revealing the true state of the nation's natural, social, human and human-made capital. Mainstream media were lukewarm about these new ideas, wondering what the GPI had to do with the Dow Jones Industrial Average reaching new phoenix highs. For a nation so obsessed with economic performance, this cold shower was strange but honest. Today, the economic mantra that more economic growth (more production; more consumption) and increasing productivity automatically leads to improved wellbeing, continues despite an honest accounting of the state of real wealth.

The GDP is simply a gross tally of the monetary transactions in the nation. The more people spend, the more the GDP goes up. If the result is greater than the year before then we say the economy has 'grown' and that we are better off. The word 'growth,' which pervades economic reportage and debate, means simply this: Americans and Canadians spent more money than they did the year before.

The ideal economic or GDP hero is a chain-smoking terminal cancer patient going through an expensive divorce whose car is totalled in a 20-car pileup, while munching on fast-take-out-food and chatting on a cell phone. All add to GDP growth. The GDP villain is non-smoking, eats home-cooked wholesome meals and cycles to work.

The litany of crimes against genuine progress that GDP accounting sustains include:

n GDP adds up all money transactions without accounting for costs.

n GDP takes no account of the inequality of income, wealth and spending power.

n GDP treats crime, imprisonment, divorce and other forms of family and social breakdown as economic gain, yet the value of housework, parenting and volunteering count for nothing.

n GDP increases with each environmental calamity, each polluting activity and then again in repairing the damage.

n GDP does not account for the depletion or degradation of natural resources and the environment.

n GDP treats war expenditures as economic gain both during the destruction and the rebuilding phases.

n GDP ignores the liabilities of living on debt and foreign borrowing.

Intuitively we know, feel and experience flaws in the GDP and growth logic, based on our own experience as managers of households or businesses. Just because we are spending more money does not mean that life is getting better. Many of us feel fatigued by what Juliet Schor calls 'capitalism's squirrel cage' - an insidious cycle of work and spend, where families work longer hours to support a material lifestyle that is always slightly beyond their reach. We spend too much time on the job, too much time commuting to the office, with too little time left for family, friends, chores or leisure.

In contrast to the GDP, the GPI attempts to measure the costs and benefits of human, social, natural and human-made capital. The GPI starts with personal/household consumption expenditures, which make up 65 percent of the U.S. GDP. To this figure we then:

n adjust for income inequality…the gap between rich and poor;

n add the value of housework and parenting and the value of volunteer work;

n add the value of the service from household infrastructure;

n add the value of the service from streets and highways;

n subtract the value of time including the cost of lost leisure time, family breakdown, commuting time and underemployment;

n subtract the cost of crime, auto accidents and cost of consumer durables;

n subtract the cost of long-term environmental degradation, air pollution, water pollution, ozone depletion, air pollution, noise pollution, loss of farmland, loss of forests, loss of wetlands ; and

n adjust for net capital formation and net foreign borrowing.

In 1999 co-author, Jonathan Rowe, and I updated the U.S.GPI account. The results were disturbing, showing an accelerated erosion of natural, human and social capital. According to the GDP, there has been almost continual economic improvement for the last 50 years. People are spending more money. By the standard of the GDP, this means life has gotten continually better. The GPI tells a different story. It suggests that the economy did indeed improve until around 1973, but then it reached a kind of turning point.

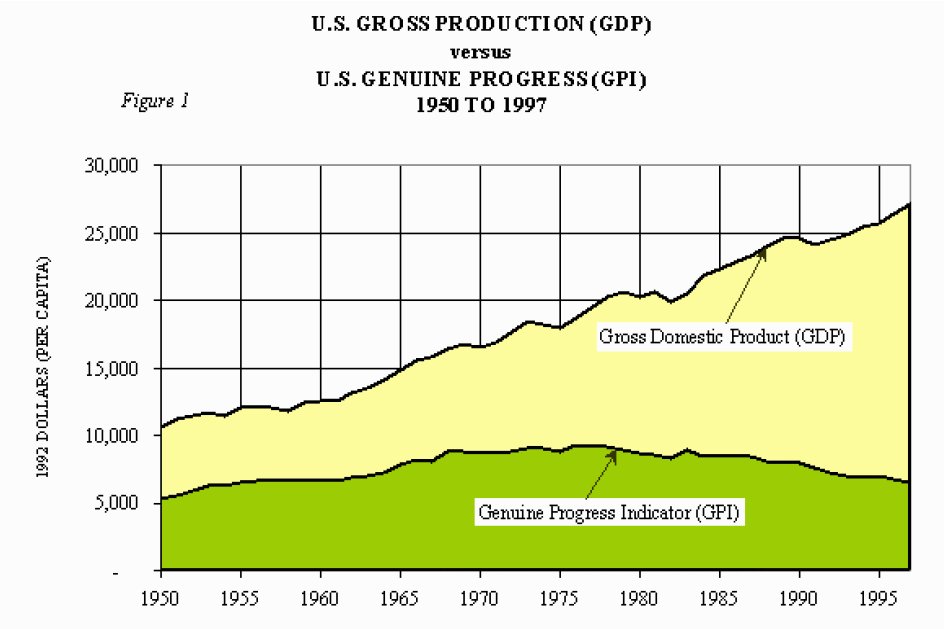

Figure 1 shows that while U.S. GDP per capita has shown relentless real (adjusted for inflation) positive growth since 1950, the U.S. GPI per capita has been sinking ever since the mid-1970s. In fact, the 1990s have seen the largest erosion of the real GPI, which declined at an average annual rate of 2.7 percent, compared with per capita GDP growth of 1.4 percent.

Figure 1

The main factors driving the decline in the U.S. GPI include:

n income inequality (the gap between the rich and everyone else) has risen 18 percent, reaching its highest level in 50 years - by 1997 the top 20 percent of households were getting almost 48 percent of the national income while the lowest 20 percent of households got only 4 percent;

n negative costs from the depletion of non-renewable resources (oil, gas, coal);

n negative costs of lost leisure time and family breakdown; and

n increasing foreign indebtedness.

Putting dollar values to the 1997 GPI figures, consider that of the US$7.27 trillion GDP (in 1992 dollars), $4.91 trillion (68 percent) was personal consumption expenditures. On the positive side of the GPI, the value of unpaid housework, parenting and volunteerism - a benefit of $1.97 trillion - represented 27 percent of the 1997 U.S. GDP value. On the negative side, the cost of pollution and environmental degradation - a cost of $1.44 trillion - represented 20 percent of the 1997 U.S. GDP. The cost of resource depletion (including loss of forests, farmland, wetlands) was $1.84 trillion or 25 percent of U.S. GDP.

While similar GPI accounting work in Canada has only just begun, the results are no less sobering. Prof. Ron Colman, director of the GPI Atlantic Project, has estimated the value of unpaid housework/parenting, volunteerism and the cost of crime. Colman has estimated that modern two-parent working Canadian families, despite numerous household innovations, are actually spending MORE time working for pay and at unpaid housework and childcare than 100 years ago. Indeed, both Canadian and U.S households appear to be caught in a cycle of earning less, spending more, going deeper into debt and working harder to pay for their increased expenses. The GPI gives concrete expression to something many Canadians and Americans sense about the economy; that we are living off natural, human and social capital. We are cannibalizing both the social structure and the natural habitat to keep the GDP growing at the rate the experts and money markets deem necessary. Yet the nation's economic reportage and debate proceed as though this erosion of real wealth does not exist. The indicators that should alert us to such tendencies serve to hide them instead.

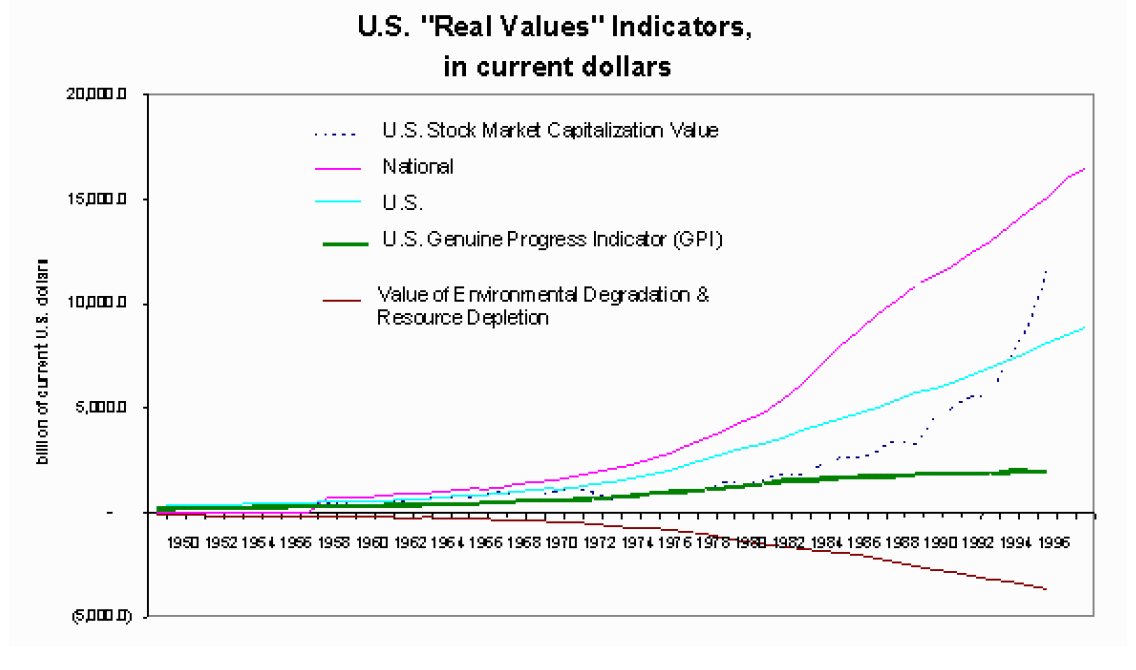

Furthermore, there is growing disconnect between real wealth (as embodied by the GPI) and financial wealth (measured by the U.S. stock market capitalization value, the U.S. GDP and U.S. national debt). David Korten's Post-Corporate World provided inspiration for the following graph. We provided the actual data and produced Figure 2 showing the gulf between financial-fiat wealth and real wealth. This reaffirms our intuition that the world of finance and global capitalism is hopelessly out of touch with achieving genuine progress.

Figure 2: Financial Wealth vs. Real Wealth

New national and provincial accounting systems like the GPI might not necessarily lead to smarter economic policies. However, retiring the laments of Küznets and economic ghosts of Keynes will go a long way toward ensuring governments begin to account for genuine well-being and the true state of our natural, social and human capital. This journey must be taken with hopeful expectations to reclaim, as per T.S. Eliot, 'the wisdom we have lost in knowledge and the knowledge we have lost in information.'

Mark Anielski is Senior Fellow with Redefining Progress (San Francisco) and Director of the Green Economics Program at the Pembina Institute for Appropriate Development. This article appeared in the October/November 1999 issue of Encompass magazine.