OVERVIEW

MANAGEMENT

PERFORMANCE

POSSIBILITIES

CAPITALS

ACTIVITIES

ACTORS

BURGESS

Business |

|

Burgess COMMENTARY |

|

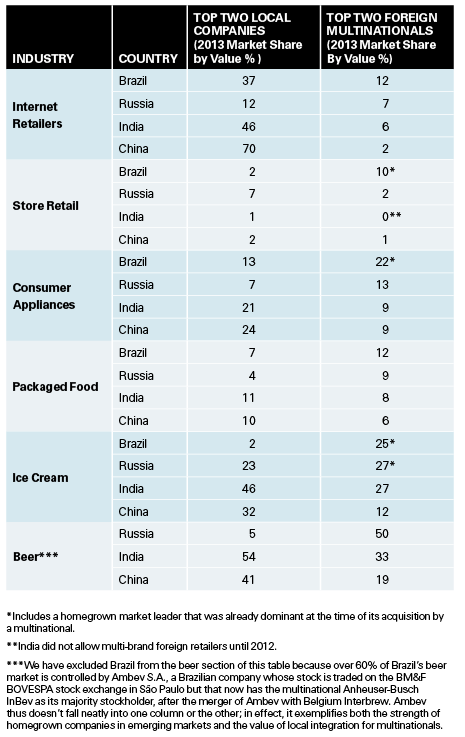

The New Mission for Multinationals As local companies win an increasing share of markets in emerging economies, multinationals need to let go of their global strategies and embrace a new mission: Integrate locally and adapt globally. China-based Xiaomi Inc. became the number one smartphone company in China after only five years in business. Xiaomi’s phones are manufactured by the same companies that make phones for its multinational competitors. Image courtesy of Flickr user Kārlis Dambrāns Something strange seems to be happening as globalization marches forward: Increasingly, powerful local companies are winning out against multinational competitors. This is especially true in emerging markets, where multinationals are assumed to enjoy superiority and their CEOs are counting on growth. Unilever CEO Paul Polman recently pointed out that his stiffest competition comes from fast-growing local companies. “We don’t see Procter & Gamble as our toughest competitor,” he noted. “Most of our competitors in emerging markets are regional players.”1 This sentiment appears widespread: According to one survey, 73% of executives at large multinational companies considered that “local companies are more effective competitors than other multinationals” in emerging markets.2 Not long ago, many observers worried that ever-expanding multinationals, many of which had revenues exceeding the gross domestic product of smaller countries, were going to take over the world. But consider this evidence: In China’s ice cream market, Unilever and Nestlé S.A. had won market shares of only 7% and 5%, respectively, by 2013 — despite decades of investment. The market is dominated by two companies that most people outside of China have probably never heard of: China Mengniu Dairy Co. Ltd., with a 14% market share, and Inner Mongolia Yili Industrial Group Co. Ltd., with 19%. Meanwhile, in the Chinese market for laundry detergent, Procter & Gamble was the leading foreign brand, with an 11% share in 2013, but it was overshadowed by two China-based companies: Nice Group Co. Ltd., with more than 16% of the market, and Guangzhou Liby Enterprise Group Co. Ltd., with 15%. The home appliance market is similarly structured. Chinese companies dominate the market, with Haier Group at 29%, followed by Midea Group (12%) and Guangdong Galanz Group Co., Ltd. (4%). The two top multinational competitors, Germany’s Robert Bosch GmbH and Japan’s Sanyo Electric Co. Ltd., have only niche positions (each with less than 4%). MULTINATIONALS FACE INCREASING COMPETITION FROM HOMEGROWN COMPANIES

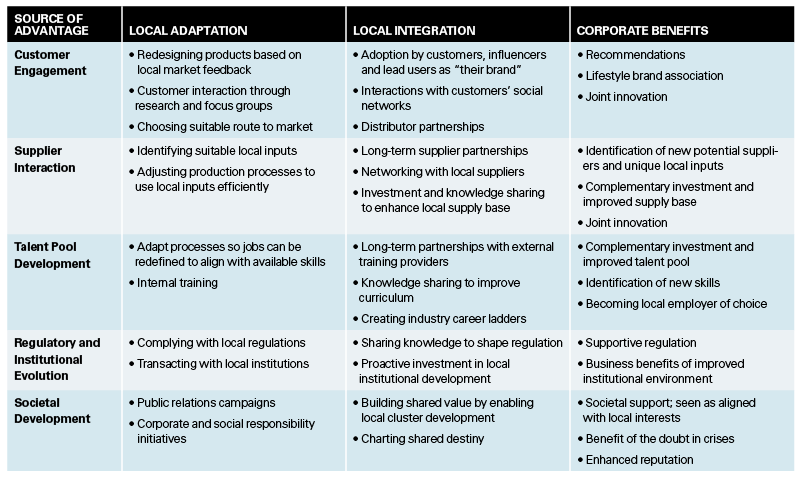

China isn’t the only market where multinationals are losing ground to local companies. The same pattern is being repeated in other emerging markets: in India’s ice cream and beer markets; in “brick-and-mortar” retailing in Brazil, Russia, India and China; in smartphones in India and China; and even in e-commerce, where locally based companies including China’s Alibaba, India’s Flipkart and Russia’s Ulmart have dominated Amazon and eBay. (See “Multinationals Face Increasing Competition From Homegrown Companies.”) Across a broad swath of industries, multinationals are losing ground in emerging markets to local players. However, our research also highlights cases where multinationals have resisted the market gains of local competition, whether through first-mover advantage or through acquiring the leading local players and then nurturing their local identity and strengths. (See “About the Research.”) About the Research This research began when we were conducting an unrelated study of competition between multinationals and local companies in fast-moving consumer goods markets in China. We were surprised to find that local champions were carving out larger shares of the Chinese market than their multinational competitors — even those that had been operating in China for decades. Intrigued, we wondered whether the phenomenon of local companies outcompeting established multinationals was more widespread. We collected the evidence for eight of the largest emerging markets across twelve industries between 2009 and 2013. In six industries (Internet retail, store-based retail, consumer appliances, packaged foods, ice cream and beer) the average market share of the top two homegrown brands exceeded the share of the top two foreign brands. The local champions were winning even where multinationals had substantially adapted their products to the local market. In two of the remaining industries, soft drinks and beauty/personal care products, the multinationals had maintained their lead over locals in most countries we studied by successfully differentiating their offerings on the basis of the home-country origin (such as the American lifestyle behind Coke and Pepsi, and the aura of French perfume and cosmetics). In two other industries we studied, laundry detergents and direct selling, multinationals were marginally ahead of powerful local challengers in most of the countries we studied, largely because they were early market entrants and had effectively created markets where none had existed. In the remaining two industries we analyzed, pharmaceuticals and mobile phones, multinationals remained dominant by leveraging superior, proprietary technologies that local players were unable to access on the global market. However, in the case of mobile phones, Chinese and Indian competitors were catching up quickly as the technology matured. Then, in order to better understand what gave local players an edge against multinationals, we interviewed senior managers in more than 20 of the most successful local integrators in different emerging markets. From in-depth discussions, we were able to paint a picture of the different ways local companies were able to integrate with their local environments and societies to cocreate value and how this contributed to their competitive advantage. What’s more, in the industries and emerging markets we studied, many of the top local brands increased their market share between 2009 and 2013. If multinationals are to continue to succeed against increasingly strong local competition in emerging markets, they need to move beyond the credo of “integrate globally and adapt locally.”3 Our data demonstrate the shortcomings of this traditional multinational approach in emerging markets. In dynamic markets, local adaptation is, at best, a catch-up strategy. To win in today’s global environment, companies will need to create new advantages in target markets by integrating their businesses with the local commercial networks and the society itself. They will need to help shape local markets rather than just adapt to them. The Decline of Multinational Advantage For many decades, multinationals were able to earn good returns by acting as efficient global conduits for assets that were difficult to transfer, including intangibles such as product designs, technologies, management systems and company cultures. Transfers within the multinational company were substantially more efficient than obtaining those assets through open-market transactions. In competing with local players, multinationals therefore had a competitive advantage. However, a number of forces have been eroding that advantage. First, in the drive to reduce costs, established multinationals have focused increasingly on activities with the highest returns. This meant the lower-value activities were outsourced and often offshored to emerging economies — creating global markets in which local companies can also source components and services. The outsourcing drive also necessitated more modular designs. The result is that once-closed value chains have been opened up, enabling local players to source “plug-and-play” modules that can be combined to create products very similar and sometimes superior to those of foreign multinationals. China’s Xiaomi Inc. is a case in point. Modularization and outsourcing allowed Xiaomi to produce a line of sleek and feature-packed smartphones that became number one in the Chinese market after only five years in business, with a 13.7% share in the fourth quarter of 2014, outpacing both Apple and Samsung.4 Xiaomi’s phones are based on Qualcomm reference designs, are manufactured by the same companies that make phones for its multinational competitors and use modules from the same component suppliers. Xiaomi’s MIUI software is a localized version of Google’s Android, but it has the advantage of weekly updates that draw on inputs from millions of Chinese users. A second development is the increasing globalization of the talent and business services markets. A decade ago, it was rare for experienced expatriates living in emerging markets to work for local companies. But as the global talent pool becomes more fluid, successful local companies in emerging markets employ dozens, sometimes hundreds, of foreign experts to fill gaps in their knowledge and capabilities. Hugo Barra, for example, a Brazilian, joined Xiaomi from Google, where he oversaw the rise of its Android ecosystem as vice president of Android product management. Local companies are also tapping into know-how from global professional services firms (design, engineering, consulting, auditing, financial and legal) that are now eager to diffuse best practices in ways that were previously available only to multinationals. Moreover, there is now a large contingent of top-tier students from emerging countries who have returned home after graduating from the world’s best universities. Natura Cosmeticos Cosmetics Frangrances Brazil’s Natura leads its home market in cosmetics, fragrances and toiletries in part by using local ingredients and integrating its sales activities with community life. Image courtesy of Natura Cosméticos S.A. Third, successful local companies have increasing opportunities to use offshore mergers and acquisitions to capture assets, capabilities and know-how that would otherwise take years to accumulate. Foreign takeovers still face many barriers, including political opposition, but data reveal that companies in emerging markets are making large numbers of acquisitions overseas and that some of these acquisitions are aimed at accessing knowledge that can be brought back home and used to close the gap with multinationals (as opposed to expanding market share abroad).5 In sum, multinationals are no longer the only entities that can act as efficient conduits for transferring assets and knowledge around the globe. Companies based in emerging markets can access and acquire brands, product modules, technologies and talent from increasingly efficient global markets and use these assets to fuel innovation and bolster their competitiveness in their home markets. “Home Team” Advantages Even if globalization doesn’t allow local companies to access all of the technologies and brand equity that multinationals might enjoy, successful companies in emerging markets can often compensate for whatever deficits they have with what we call “home team” advantages. We identified five strategies that help locals build these advantages: (1) engaging deeply with customers and end users; (2) partnering with local suppliers; (3) fostering development of the local talent pool; (4) shaping the regulatory and institutional environment; and (5) participating in the broader development of social value. Local companies don’t use these mechanisms out of altruism but because they create more value, some of which they share in the form of higher profits. The process is so natural that local companies are often unaware that it is distinctive or of its role in their success. One company that epitomizes how local companies create home-team advantages through local integration is Natura Cosméticos S.A., Brazil’s market leader in cosmetics, fragrances and toiletries. Understanding how companies such as Natura benefit from local integration is the first step toward learning how to go beyond adaptation. Natura, with a 20.4% share of the cosmetics market in Brazil (the world’s third-largest cosmetics market), outpaces its multinational competitors (including L’Oréal, P&G and even Avon, which has been in Brazil since 1958). Some 60% of all Brazilian homes contain Natura products, and the company had revenues of $3.3 billion in 2013.6 The first factor in Natura’s success is its close integration with distributors and, through them, its customers. Rather than selling through established retail channels, Natura has built up a sales network of more than one million consultoras (consultants) — typically women, who often go on to become pillars of their local communities. Instead of assigning consultants a territory, Natura lets individual consultants define their own markets by their social relationships, allowing Natura to become networked into the local community. Natura also eschews the typical multilayer structure of direct sales organizations such as Avon. Instead, it employs relationship managers who each deal directly with a maximum of a few hundred consultants. Through monthly meetings originally designed to provide product and sales training, Natura found that its relationship managers became confidants and role models on topics ranging from birth control, hygiene and health care to children’s education, social rights and democracy. By integrating its sales activities with community life and fostering the development of civil society, Natura found that it could create social value that also bolstered its profitability. Conventional sales commissions and incentive schemes used by competitors were no match for the degree of personal commitment and pride that Natura engendered among consultants by creating a role that allowed them to become respected and influential in their neighborhoods. A second element in Natura’s success is its integration with the local supply base that it helped to build. The company has more than 5,000 small suppliers and 32 local communities harvesting natural ingredients from rain forest trees and plants including andiroba, cupuaçu and priprioca. Natura invested in product formulations that used natural materials from Brazil’s diverse biosphere, and it worked closely with local communities and suppliers, often in remote regions, to develop their skills and methods. Its relationship with local suppliers has also helped Natura to become a leader in environmentally friendly packaging: The company led its industry in introducing refill pouches, reducing its use of plastic by 83%. Local suppliers like being associated with Natura because the relationship helps improve their capabilities and enhance their reputation. In return, they offer Natura lower costs and more responsive service. The third element in Natura’s success is that it has become a local employer of choice. Natura has won awards in Brazil, ranging from “most admired company” to “best place for women to work” and “most socially responsible company.” Its reputation has attracted Brazilian graduates, managers and technical staff who not only are well qualified but also aspire to be part of company that is participating in the development of their country. The fourth factor is Natura’s ability to work with regulators and the government to shape legislation in ways that are supportive of its business while also benefiting the country. Rather than simply complying with regulations the way many companies do, Natura has worked with government to revise legislation on biodiversity in Brazil, protecting its raw material sources as well as the environment. Working with local authorities in remote northern Brazil, Natura spearheaded a recently opened $80-million cluster of laboratories and factories that further expands the use of local raw materials. Finally, Natura is able to derive benefits from its local integration and commitment to Brazilian society. The company’s motto, “Bem Estar Bem” (literally, “Well Being Well”) applies to individual customers, employees, consultants and suppliers, and also to the broader society. Applying the principle, Natura has been supportive of groups involved with local social and environmental issues and instrumental in building public awareness about the need for sustainability in Brazil. It was a pioneer in the use of the “triple bottom line,”7 which other Brazilian companies have followed, reinforcing the local perception that Natura is a company worthy of support. Successful local companies such as Natura or Xiaomi derive enormous competitive benefits from the fact that they are deeply integrated into local commercial networks and have built symbiotic relationships with the local society. As outsiders, multinationals start with a handicap in matching these advantages, not least because of their predilection to import and adapt what has worked elsewhere. So given the home-team advantages of local competitors and the eroding relative advantages of cross-border arbitrage as globalization enters a new phase, how can multinationals respond? Local Adaptation Is Not Enough Faced with the different demands of local markets, multinationals have become expert in adapting their products and services to local conditions. Even McDonald Corp.’s “Big Mac,” the epitome of a global product, has been adapted for local markets; for example, there’s a Chicken Maharaja Mac in India and a kosher variant in Israel served without the cheese. But this kind of adaptation — even if it involves localizing the supply chain — doesn’t generate the kinds of benefits that local companies such as Natura can leverage as national champions. To reap the rewards of local integration, companies need to become embedded in local distribution, supply, talent and regulatory networks as well as in the broader society. To match the advantages of local companies, multinationals in effect need to become like amphibians, who often are born in one environment (water) but are also at home in another (on land). Mission: Showing the Value of Social Business Initiatives To understand what this means, it helps to review how local integration provides specific competitive advantages that can’t be matched by local adaptation alone, and also what some leading-edge multinationals have done to obtain the benefits of local integration. Customer Engagement Multinationals know how to research customer needs in a local market and adapt their products to improve their fit. They may even cocreate product adaptations and adapt their business models with input from local customers and distributors. But as we saw with Natura, locally integrated companies forge deep relationships with customers in ways that go well beyond market feedback. By connecting with customers’ lives and working closely with local influencers and lead users, companies can create new markets or embed their products and brands into local networks. The deep, long-term commitment that local integration involves also encourages distributors to coinvest in everything from dedicated marketing to specialized logistics that helps to expand sales. Many multinationals are not naturally positioned to enter the lifeblood of customers in emerging markets, but with creative kinds of engagement they can do so. The experience of Portuguese retailing company Jerónimo Martins SGPS S.A. (JM) in Poland illustrates the kinds of contrarian strategies that may be required to compete with locals in emerging markets. Jerónimo Martins’s principal multinational rivals — Tesco, Carrefour, Metro and Ahold — imported their international formats to Poland, betting on large stores and hypermarkets on the outskirts of major cities and leveraging their latest know-how at a time when Poland was emerging from the shadow of the Soviet Union. However, during extensive visits, Jerónimo Martins Group’s then-CEO Alexandre Soares dos Santos noticed that Poles preferred buying food and other household products frugally in frequent trips to stores close to their homes. So rather than transplanting and adapting an existing formula, he decided to build, as he put it, a “Polish retailer in the land of Polish consumers.” After buying a small Polish cash-and-carry chain in 1995, JM partnered with a local entrepreneur, and a team of Polish and Portuguese managers (who became fluent in Polish) worked together to launch Biedronka (Polish for “the busy ladybug beetle”). The no-frills stores were small, colorful, welcoming and, despite being an innovative format both for JM and Poland, perfectly at home there. A couple of years later, when Biedronka had about 250 stores, JM bought out the partner and invested substantial resources to grow Biedronka nationally. Along with the expansion, JM launched a major local sourcing initiative, working with local suppliers to improve both quality and responsiveness, to reduce imports and “buy local” — creating even more social value. Biedronka now has 2,600 stores and about 14% of the Polish market, making it Poland’s biggest food retailer. Customers have come to view the company as an integral part of Polish life: It has 98% brand recognition among Poles, and more than 60% of them visit Biedronka at least once every month. Deep local integration backed by global infrastructure and know-how has paid off handsomely: In 2014, Biedronka contributed two-thirds of Jerónimo Martins Group’s sales of 12.7 billion euros. Supplier Interaction Adaptation on the supply side typically involves finding suitable local suppliers and adjusting production processes to use local inputs efficiently. But local integration often means establishing long-term partnerships with local suppliers that enable them to invest in new capacity and improve quality and productivity to build a stronger supply chain. When suppliers see you as a member of their “club,” they are more inclined to help you identify promising new suppliers and invest in joint innovation. Olam International Ltd., a Singapore-based agribusiness that operates in 65 countries, offers a good example of a multinational that captures the benefits of deep local integration with its supplier base. Many multinational agribusinesses buy commodities at a port city through a chain of middlemen. However, Olam, which had revenues of $19.4 billion in 2014, buys directly from growers, even in remote locations. Olam stations managers with MBAs from India’s top business schools in rural villages, even in countries such as Ivory Coast, where the managers can obtain early information on crop performance to improve their decisions on pricing and risk management. It builds the trust necessary for an open and honest exchange of information by working closely with more than 200,000 farmers in Africa, Asia and beyond to improve quality and productivity and helping finance the purchase of top-grade seeds and fertilizers. Olam’s integration into the supply chain means that it can provide customers with guarantees of traceability and environmental certification — something that competitors buying through middlemen can’t easily match. Rather than being seen as a colonial exploiter, it is viewed as a society builder. Talent Pool Development Multinationals expanding their operations in emerging markets often encounter deficits in the skills needed to deliver high-quality products or achieve high productivity. In response, some companies adapt the job specifications to align with available skills. But when Rolls-Royce built an advanced manufacturing and research facility for aircraft engines in Singapore, it found that it could go much further to address the talent gap there. Rolls-Royce worked intensively with Singapore’s Institute of Technical Education and Nanyang Polytechnic to redesign the curricula to suit its skill requirements for 2,500 qualified local technicians and create a new degree program in aeronautical and aerospace technology. Rolls-Royce also offered opportunities for students to gain experience through internships and scholarships. As a result, Rolls-Royce has been able to dramatically expand the local pool of qualified job applicants and help build a new industry in Singapore. Regulatory and Institutional Evolution Multinationals obviously have to adapt their operations and business models to conform to local laws and regulations. But emerging markets often suffer from “institutional voids” — gaps in the rules, distorted regulations, lack of intermediaries and implementation failures.8 Instead of treating this situation as a given, local companies often gain advantage by helping shape new regulations and policies to fill these gaps. If multinationals are to compete successfully, they too need to become more proactive in shaping local institutions. This comes most naturally to multinationals from countries where close cooperation between business and government is the norm.9 Chinese companies have pursued this approach to local integration to get ahead of incumbent multinationals in Africa. For example, China Nonferrous Metals Co. Ltd. has worked closely with governments in Africa to establish special economic zones in Zambia, Mauritius, Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria and Algeria. These zones benefit from different regulatory regimes featuring tax holidays, waivers on import tariffs for raw materials, exemptions from some labor and immigration laws, and dedicated infrastructure such as port facilities. The benefits help foster a business-friendly environment that encourages foreign investment. However, few doubt that the regulations, institutions and infrastructure in these areas are tilted toward the needs of Chinese businesses. Multinationals from other countries have been reluctant to engage in these processes for fear that they might lose their business focus. But the potential benefits can’t be ignored. Societal Development One of the most challenging aspects of local integration for a multinational is being seen as sharing a common destiny with the host society, as opposed to being viewed purely as acting in the interests of foreign shareholders. Public relations and corporate social responsibility initiatives are seldom sufficient to address this issue. Having a strategy to become an integral player in helping the local society achieve its goals and aspirations is essential. Sam Palmisano, the former CEO and chairman of IBM, described the requirement this way: “We didn’t simply enter markets … We made markets, working with leaders in business, government, academia and community organizations to help advance their national agenda and address their societal needs — being a force for modernization and progress.”10 Multinationals that can do this will find that broad swaths of society will get behind them and help propel their business forward. No amount of local adaptation can deliver the business benefits of local integration enjoyed by companies that pursue the five strategies we have discussed. (See “Local Integration Goes Far Beyond Adaptation.”) But our research suggests that there are two additional ways in which multinationals can integrate at a local level. The first approach is to acquire a major local company and then manage the post-acquisition integration to preserve the links between the original company and local customers, suppliers and society; the second approach is to enter the market early. Unilever followed the first approach in its ice cream business when it acquired the local market leaders in several emerging markets: Kibon in Brazil, Inmarko in Russia, and Helados Holanda in Mexico. The acquired companies had pioneered the prepackaged ice cream market in their respective countries with brands and operations deeply integrated in the local fabric — strengths that Unilever has sought to nurture. LOCAL INTEGRATION GOES FAR BEYOND ADAPTATION To succeed against increasingly strong local competition in emerging markets, multinational companies can no longer just adapt their products to local markets; instead, multinationals need to integrate locally. Local integration requires different types of engagement, deeper interactions with the local economy, and more investment than adaptation, but the benefits can be substantial.

A second way multinationals can further integrate at the local level is by committing to emerging markets early. Despite some risks, this offers opportunities to “build in” local integration from the start and to co-evolve as the market develops. Danish brewer Carlsberg Breweries A/S, for example, entered Russia when the local beer market began to take off in the 1990s. Having shaped the modern beer industry, Carlsberg and its consortium partners now enjoy a 38% market share. Global Implications of Local Integration The need for local integration does not mean that multinationals should go back to becoming loose federations of subsidiaries, where powerful country managers have virtual autonomy that’s bounded only by financial controls. Rather, the modern multinational needs to remain globally coordinated. But the pursuit of local integration poses constraints and opportunities for the way multinationals organize their global activities. We see six important implications. First, the mindset of both headquarters and local leadership needs to shift. Local adaptation is relatively easy to coordinate and control from afar, but local integration is not. Becoming entwined with the lives of thousands of local distributors and representatives, innovating together with local suppliers or proactively shaping regulations requires being on the ground. Headquarters needs to share control over the corporate future and abandon the idea that local subsidiaries must march in lockstep and adapt standard product designs and processes. For the managers of local subsidiaries, this means achieving the benefits of local integration without undermining what differentiates the multinational company or the benefits of an efficient global supply chain. Second, the role and caliber of local leaders needs to be upgraded. This goes counter to the recent trend in many multinationals of relegating country managers to narrower, ambassadorial roles. Future country heads will need more influence to manage the evolution of local markets in concert with local customers, suppliers, regulators and the talent pool. They will need to draw on the multinational’s global network of resources to shape a winning local strategy. Companies operating in important markets such as China may even need to treat those markets as “second homes,” with local leaders working directly with the top management team and local integration receiving as much emphasis as it does in the home market.11 Third, becoming locally integrated in multiple countries implies changes, perhaps even duplication, in certain activities. Embracing a local society’s progress may require coinvesting in the development of a local supplier network even though the company already has capable suppliers in another country. Companies will need to make exceptions to corporate-wide processes, and they will need to retool business models to accommodate new and diverse kinds of partnerships. In the process, managers will need to pay attention to new risks, including corruption and intellectual property theft. Helados Holanda Unilever acquisition When it acquires companies such as Mexico’s Helados Holanda, Unilever seeks to preserve the links between the original company and its customers and suppliers. Image courtesy of Unilever. Fourth, companies seeking to grow through local acquisitions will need to adjust the way they do business. A key question in preacquisition due diligence is how well integrated the acquisition candidate is with its local customers, distributors and suppliers as well as with its home country’s institutions and society. Following acquisitions, managers should proceed carefully to improve efficiency and add new technologies, products and processes while still nurturing local identity and critical local relationships. Fifth, the imperative of local integration requires multinational executives to make bold moves into developing markets — even before the economic potential is proven. Waiting until a market is already established will consign the company to “outsider” status.12 Finally, headquarters executives also need to seek out the new global opportunities that local integration spawns. Interactions with local partners will generate new knowledge and unexpected opportunities for global innovation. These opportunities will come from new ways of learning from the world and exposure to local innovations and different business models rather than from simply implementing and adapting formulas crafted at home.13 In short, more local integration has a corollary: The global organization will need to adapt as well. This global adaption will be painful because it undermines orthodox cost efficiencies and traditional headquarters powers. Instead of pushing from the center, the new mission of multinationals is about fostering pull by local units from the center. A New Multinational Mission Some multinationals can be successful without local integration by turning their foreignness into a virtue. For example, Coca-Cola, Levi Strauss and Disney can continue to sell a piece of American lifestyle, Prada can continue to clothe its foreign customers in Italian fashion sense, and Porsche and BMW can profit from promoting German engineering. Excessive adaptation or local integration would risk undermining the very thing that makes such brands uniquely attractive. But many other companies that have relied on the traditional advantages of multinationals will continue to see their advantages erode as globalization allows local champions to access similar knowledge and capabilities. To restore their edge, senior executives working for multinationals must make a choice: Either build on their foreignness or integrate locally to create new layers of advantage. Companies that simply rely on adapting the formula they perfected at home will be “stuck in the middle” — neither benefiting from foreign distinctiveness nor enjoying the benefits of becoming a local insider. Capturing the huge benefits of becoming locally integrated will require both country and headquarters executives and the global organization to change. Multinationals that choose this path will need to look beyond the global strategies that have dominated their thinking over the past 30 years and embrace a new mission: Integrate locally and adapt globally. REFERENCES (14) 1. S. Daneshkhu, “Stiffest Competition From Local Business, Says Unilever Chief,” Financial Times, July 30, 2014, p. 1. 2. V. Chin and D.C. Michael, “2014 BCG Local Dynamos: How Companies in Emerging Markets Are Winning at Home,” The Boston Consulting Group, July 10, 2014, p. 6. 3. C.K. Prahalad and Yves L. Doz summarized the “multinational mission” in 1987 as finding a way to combine the benefits of “global integration” (global-scale economies and a global supply chain that combined the most efficient locations) and “local responsiveness” (adapting to the peculiarities of local markets). See C.K. Prahalad and Y.L. Doz, “The Multinational Mission: Balancing Local Demands and Global Vision” (New York: The Free Press, 1987). Christopher A. Bartlett and Sumantra Ghoshal subsequently laid out a blueprint for a “transnational” company that could be both globally integrated and yet also highly adapted to local markets. See C.A. Bartlett and S. Ghoshal, “Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution” (Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Press, 1989). More recently, Pankaj Ghemawat reminded us that the world remains “spiky” and “semi-globalized” and that companies need strategies to adapt to local differences as well as overcoming and arbitraging them. See P. Ghemawat, “Redefining Global Strategy: Crossing Borders in a World Where Differences Still Matter” (Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Press, 2007). 4. IDC Asia/Pacific Quarterly Mobile Phone Tracker, February 2015, www.idc.com. 5. International Institute for the Study of Cross-Border Investment and M&A, ”XBMA Annual Review 2014,” www.XBMA.org. 6. Natura Annual Report 2013, natura.infoinvest.com/br. 7. The “triple bottom line” is a business concept coined by John Elkington. See J. Elkington, “Cannibals With Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business” (Oxford, U.K.: Capstone Publishing, 1997). 8. T. Khanna and K.G. Palepu, “Winning in Emerging Markets: A Road Map for Strategy and Execution” (Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Press, 2010). 9. M.F. Guillén and E. García-Canal, “The New Multinationals: Spanish Firms in a Global Context” (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2010). 10. S.J. Palmisano, “Re-Think: A Path for the Future” (New York: Center for Global Enterprise, 2014). 11. Y. Luo, “From Foreign Investors to Strategic Insiders: Shifting Parameters, Prescriptions and Paradigms for MNCs in China,” Journal of World Business 42, no. 1 (March 2007): 14-34. 12. In an extension of their seminal paper on internationalization, Jan Johanson and Jan-Erik Vahlne point out that it is exactly this difficulty of breaking into the web of already established relationships that presents the barrier to entering overseas markets rather than their “foreignness” per se. See J. Johanson and J.-E. Vahlne, “The Uppsala Internationalization Process Model Revisited: From Liability of Foreignness to Liability of Outsidership,” Journal of International Business Studies 40, no. 9 (December 2009): 1411-1431. 13. J. Santos, Y. Doz and P. Williamson, “Is Your Innovation Process Global?,” MIT Sloan Management Review 45, no. 4 (summer 2004): 31-37. i. The market share statistics are drawn from Euromonitor International data. ABOUT THE AUTHORS José F.P. Santos is an affiliated professor of practice in global management at INSEAD in Fontainebleau, France. Peter J. Williamson is a professor of international management at the University of Cambridge’s Judge Business School in Cambridge, United Kingdom. |

|

Research Feature ... José F.P. Santos and Peter J. Williamson

May 18, 2015 Reading Time: 25 min |

| The text being discussed is available at and http://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/the-new-mission-for-multinationals/ |